There is considerable controversy over the total number of genes in the human genome. The number of protein-coding genes is pretty well established at somewhere between 19,500 and 20,000. It's the number of non-coding genes that's disputed.

There's general agreement on the number of well-defined small RNA genes such as snRNAs, snoRNA, microRNAs etc. Similarly, the number of ribosomal RNA and tRNA genes is known. The problem is with identifying genuine long non-coding RNA genes (lncRNA genes). Estimates vary from less than 20,000 to more than 200,000 but most of these estimates fail to define what they mean by "gene." Many scientists seem to think that any detectable transcript must come from a gene.

This doesn't make any sense since we know that spurious transcripts exist and they don't come from genes by any meaningful definition of gene. The only reasonable definition of a molecular gene is a DNA sequence that's transcribed to produce a functional product.1

The idea that spurious, non-functional, transcripts exist has been described in the scientific literature for many decades. One of my favorites is in a paper by Ponting and Haerty (2022) quoting another paper from thirteen years ago by Ulitsky and Bartel.

The cellular transcriptional machinery does not perfectly discriminate cryptic promoters from functional gene promoters. This machinery is abundant and so can engage sites momentarily depleted of nucleosomes and rapidly initiate transcription. The chance occurrence of splice sites can then facilitate the capping, splicing, and polyadenylation of long transcripts. A very large number of such rare RNA species are detectable in RNA-sequencing experiments whose properties are virtually indistinguishable from those of bona fide lncRNAs. Consequently, “a sensible [null] hypothesis is that most of the currently annotated long (typically >200 nt) noncoding RNAs are not functional, i.e., most impart no fitness advantage, however slight” (Ulitsky and Bartel, 2013: p. 26).

The important point here is that the correct null hypothesis is that these transcripts don't have a biologically relevant function and the burden of proof is on researchers to demonstrate function before assigning them to a genuine gene. My colleagues at the University of Toronto made the same point in a paper published in 2015.

In the absence of sufficient evidence, a given ncRNA should be provisionally labeled as non-functional. Subsequently, if the ncRNA displays features/activities beyond what one would expect for the null hypothesis, then we can reclassify the ncRNA in question as being functional. (Palazzo and Lee, 2015)

There are a number of well-defined lncRNAs that have been shown to have distinct reproducible functions. The key question is how many of these biologically relevant lncRNA genes exist in the human genome. I struggled with the answer to this question when I was writing my book. I finally decided to make a generous estimate of 5000 non-coding genes and that implies several thousand lncRNA genes (p. 127). I now think that estimate was far too generous and there are probably fewer than 1000 genuine lncRNA genes.

I have not scoured the literature for all the examples of human lncRNAs having good evidence of function but my impression is that there are only a few hundred. This post was incited by a recent publication by researchers from the Hospital for Sick Children and the University of Toronto (Toronto, Canada) who characterized another functional lncRNA called CISTR-ACT that plays a role in regulating cell size (Kiriakopulos et al., 2025).

I was prompted to revisit this controversy by the accompanying press release that said ...

Unlike genes that encode for proteins, CISTR-ACT is a long non-coding RNA (or lncRNA) and is part of the non-coding genome, the largely unexplored part that makes up 98 per cent of our DNA. This research helps show that the non-coding genome, often dismissed as ‘junk DNA’, plays an important role in how cells function.

We're used to this kind of misinformation2 in press releases but I thought it would be a good idea to read the paper. As I expected, there's nothing in the paper about junk DNA but here's the first sentence of the introduction.

The human genome contains more long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) than protein-coding genes (GENCODE v49) which regulate genes and chromatin scaffolding.

The latest version of GENCODE Release 49 claims that there are 35,899 lncRNA genes. This is the only reference in the Kiriakopulos et al. paper to the number of lncRNA genes. There's no mention of the controversy and none of the papers that discuss the controversy are referenced.

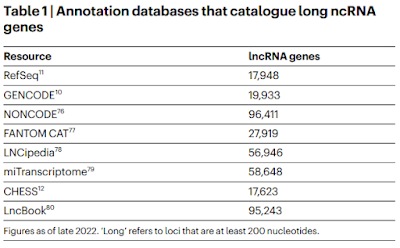

The GENCODE number is close to the latest version of Ensembl, which lists 35,042 lncRNA genes. I couldn't find any good explanation for these numbers or for the definition of "gene" that they are using but what's interesting is how these numbers are climbing every year; for example, a paper from two years ago listed a number of sources and you can see that the RefSeq and GENCODE numbers are much smaller than today's numbers (Amaral et al., 2023).3

We intend to provoke alternative interpretation of questionable evidence and thorough inquiry into unsubstantiated claims.Ponting and Haerty (2022)

It's perfectly acceptable to state your preferred view on lncRNAs when you publish a paper. The authors of the recent paper may want to believe that there are more lncRNA genes than protein-coding genes but I think it's important for them to define what they mean by "gene" when they make such a claim. What's not acceptable, in my opinion, is to ignore a genuine scientific controversy by not mentioning in the introduction that there are other legitimate views.

It's a shame that they didn't do that because their paper is a good example of the hard work that needs to be done in order to demonstrate that a particular lncRNA has a biologically relevant function.

In closing, I want to emphasize the recent review by Ponting and Haerty (2022)4 that points out the importance of the problem and the kinds of experiments that need to be done in order to establish that a given RNA comes from a real gene. This is how a scientific controversy should be addressed. Here's the abstract of that paper ...

Do long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) contribute little or substantively to human biology? To address how lncRNA loci and their transcripts, structures, interactions, and functions contribute to human traits and disease, we adopt a genome-wide perspective. We intend to provoke alternative interpretation of questionable evidence and thorough inquiry into unsubstantiated claims. We discuss pitfalls of lncRNA experimental and computational methods as well as opposing interpretations of their results. The majority of evidence, we argue, indicates that most lncRNA transcript models reflect transcriptional noise or provide minor regulatory roles, leaving relatively few human lncRNAs that contribute centrally to human development, physiology, or behavior. These important few tend to be spliced and better conserved but lack a simple syntax relating sequence to structure and mechanism, and so resist simple categorization. This genome-wide view should help investigators prioritize individual lncRNAs based on their likely contribution to human biology.

1. See Wikipedia: Gene; What Is a Gene?; Definition of a gene (again); Must a Gene Have a Function?.

2. No knowledgeable scientist ever said that all non-coding DNA was junk. We've known about non-coding genes for more than half-a-century.

3. See How many genes in the human genome (2023)?

4. See Most lncRNAs are junk

Amaral, P., Carbonell-Sala, S., De La Vega, F.M., Faial, T., Frankish, A., Gingeras, T., Guigo, R., Harrow, J.L., Hatzigeorgiou, A.G., Johnson, R. et al. (2023) The status of the human gene catalogue. Nature 622:41-47. [doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06490-x]

Kiriakopulos et al. (2025) LncRNA CISTR-ACT regulates cell size in human and mouse by guiding FOSL2. Nature communications: (in press). [doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-67591-x]

Palazzo, A.F. and Lee, E.S. (2015) Non-coding RNA: what is functional and what is junk? Frontiers in genetics 6:2(1-11). [doi: 10.3389/fgene.2015.00002]

Ponting, C.P. and Haerty, W. (2022) Genome-Wide Analysis of Human Long Noncoding RNAs: A Provocative Review. Annual review of genomics and human genetics 23. [doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-112921-123710Ulitsky, I. and Bartel, D.P. (2013) lincRNAs: genomics, evolution, and mechanisms. Cell 154:26-46. [doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.020]

39 comments :

Has anyone tried looking at a random sample of the lncRNA genes in GENCODE or whatever database and testing for function?

Your interpretation of ENCODE remains problematic when examined in light of the mechanistic requirements of RNA polymerase II–mediated transcription. transcription is known to require the coordinated assembly of a pre-initiation complex (PIC), involving multiple general transcription factors, chromatin remodeling, mediator interactions, and often enhancer–promoter communication. Such combinatorial regulation underlies tissue-specific and spatiotemporally controlled gene expression and is unlikely to arise from random genomic sequences.

While it has been proposed that pervasive transcription represents transcriptional noise arising from weak or cryptic initiation sites, this explanation raises mechanistic concerns. Even low-level initiation by RNA polymerase II generally requires at least partial PIC assembly, including factors such as TBP and associated components, rather than mere stochastic binding of individual transcription factors. Given the complexity and energetic cost of assembling even partial transcriptional machinery, it is difficult to reconcile the scale of reported pervasive transcription with the notion that it is largely aberrant and functionally irrelevant.

Furthermore, transient binding of isolated transcription factors is rarely sufficient to recruit RNA polymerase II in a manner that supports initiation, even abortive initiation. Established models emphasize that cooperative interactions among cis-regulatory elements, trans-acting factors, and chromatin context are typically required to stabilize polymerase recruitment.

@Anonymous: What do you think would happen if we inserted a large amount of random sequence DNA into human cells? Do you think we could detect transcription of that DNA?

We all understand the complexity of transcription initiation when it's required to establish frequent stable long-term transcription of a gene. We also know that the standard transcription of functional genes often involves co-operative interactions of different transcription factors and the initiation complex. These principles were established 50 years ago in studies of bacteria and phage.

Most pervasive transcription is very different. The RNA transcript does not seem to come from known functional genes. The transcribed sequence is not conserved and not under purifying selection. The transcripts are present at concentrations too low to be biologically relevant and they are usually degraded rapidly in the nucleus.

We know that pol II is capable of binding to non-promoter DNA - that's how it finds a genuine promoter by a one-dimensional search. We know that it is capable of making mistakes by transcribing random sequences of DNA to produce low levels of spurious transcripts. It seems reasonable to assume that this is what ENCODE is detecting.

RNA polymerase is not randomly starting transcription everywhere there are active molecular safeguards in the genome that keep it from doing so under normal conditions.

Not because RNA Pol II is extremely precise on its own — but because the cell uses DNA methylation and chromatin marks to suppress initiation from inappropriate sites.

Intragenic DNA methylation prevents spurious transcription initiation

Neri, Rapelli, Krepelova, Incarnato, Parlato, Basile, Maldotti, Anselmi & Oliviero — Nature 2017

@Anonymous: Eucaryotic DNA is associated with histones to form nucleosomes. There are various levels of packaging but in a typical cell the ones that concern us are the open and closed domains.

Closed domains, often referred to as heterochromatin, consist of tightly packaged nucleosomes forming three dimensional structures that make the DNA relatively inaccessible to proteins such as transcription factors. In mammals, and some other species, his structure is often stabilized by DNA methylation.

The presence of large amounts of tightly packaged DNA (closed domains) is effective in suppressing inappropriate binding of RNA polymerase and transcription factors. For example, there are more than one million potential binding sites for the average transcription factor but only about one thousand are detected in any one cell type.

This level of suppression cannot be 100% effective or else no new genes could ever be turned on by transcription factors. Current models propose that closed domains are capable of opening up transiently (breathing) and this allow access to promoters. That's why we detect hundreds of transcription factor binding sites even though those transcription factors only regulate a few genes.

The transient opening of closed domains is partly what leads to low levels of transcription all over the genome in spite of the fact that much of the genome is repressed most of the time. If you believe that thousands of genuine non-coding genes are activated in dozens of different cells types then you also have to explain how that happens if suppression of transcription is as efficient as you would like to believe.

The other important factor is that active genes in open domains take up a much larger fraction of the genome than most people believe. Keep in mind that more than 40% of the human genome is devoted to genes (transcribed sequences) and that there are about 10,000 housekeeping genes active in most cell types. This is why many of the spurious transcripts initiate within introns and why many of them come from the opposite strand of a well-defined gene.

The paper you quoted (Neri et al., 2017) addressed this issue. They showed that DNA methylation WITHIN genes (intragenic) helps to suppress - but not eliminate - spurious transcription in highly expressed genes.

The view that spurious transcription occurs in spite of closed chromatin domains can be tested by looking at random DNA sequences that have been inserted into cells. Those DNA sequences become rapidly converted into chromatin domains that are indistinguishable from normal DNA and yet they show the same level of "pervasive" transcription producing low levels of rapidly turned over RNA.

Open and closed chromatin domains (and epigenetics)

It is true that chromatin is dynamic: nucleosomes transiently unwrap and chromatin-associated proteins exchange over time, a phenomenon often referred to as chromatin breathing. However, this dynamism does not equate to transcriptional permissiveness, particularly in heterochromatin.

1. Repression in heterochromatin is maintained by dynamic reinforcement, not static closure

Heterochromatin is not silent because it is permanently inaccessible, but because its repressive state is continuously re-established. Core heterochromatin marks such as H3K9me3 are read by proteins like HP1, which in turn recruit the same histone-modifying enzymes that re-install these marks on neighboring or newly deposited nucleosomes. This creates a self-reinforcing “write–read–rewrite” loop.

As a result, transient chromatin opening events are rapidly counteracted. The timescale of repressive mark re-establishment is faster than the timescale required for transcription initiation, elongation, and transcript stabilization. Thus, chromatin breathing does not provide a meaningful window for productive transcription.

In short, heterochromatin is dynamically stable: it tolerates local fluctuations without losing its functional repression.

2. Spatial sequestration limits access to transcription machinery

Heterochromatin is not only defined by local chromatin marks but also by its nuclear positioning. Large heterochromatic domains are preferentially localized to repressive nuclear compartments, such as the nuclear periphery or chromocenters. These compartments are depleted of transcription factors, RNA polymerase II, and co-activators.

Even if a heterochromatic region transiently becomes more accessible at the nucleosome level, it remains physically separated from transcriptional hubs. This spatial insulation drastically reduces the probability that RNA polymerase will engage the DNA during these brief accessibility events.

@Anonymous: Transcripts from just about the entire human genome have been detected by analyzing RNAs from a wide variety of tissues. The ones outside of known genes are present at very low levels and are rapidly degraded in the nucleus. The vast majority of corresponding DNA sequences are not conserved and do not have any of the characteristic of functional genes.

Spurious or accidental transcription has been documented in several species and we know that random DNA sequences are transcribed at the same low level seen for naturally occurring DNA. There is abundant evidence that most of our genome is junk suggesting that the transcripts are not biologically relevant.

We know that when new genes are transcribed, the relevant promoter regions must transition from heterochromatin to open chromatin and the only plausible mechanism is localized breathing that allows newly produced transcription factors to bind and initiate transcription.

In spite of all this, you maintain that heterochromatic regions are so strictly maintained that only genuine promoter regions can be activated and spurious transcription is impossible. You maintain that genes cover almost 100% of the human genome because any region of DNA that is transcribed must be part of a biologically relevant gene.

I think your position makes no sense.

Sorry, but your criteria for detecting non-coding RNA functionallity including ( purifying selection of sequence, RNA abundance and lifespan), don't seem persuasive to me. Because we have found numerous functional Non-coding RNAs with exactly those properties. I even think they need to be in low abundance and short-active, to do their regulatory jobs effectively. In summery:

Lack of strong sequence conservation does not preclude function, as regulatory roles are often preserved through genomic position, transcriptional context, secondary structure, or interaction networks rather than nucleotide sequence alone.

Similarly, short RNA half-life reflects a design for transient, context-dependent regulation, enabling rapid response to stimuli and precise temporal and spatial control, rather than indicating transcriptional noise.

Low abundance is also typical for these RNAs; functional effects often depend on cis-acting mechanisms, local chromatin interactions, or stoichiometric binding with protein partners, rather than high molecular concentration.

Collectively, these features are descriptive properties of regulatory ncRNAs and should not be interpreted as evidence of non-functionality

"The timescale of repressive mark re-establishment is faster than the timescale required for transcription initiation, elongation, and transcript stabilization.

On average? Possibly. But in the brownian environment of the cell, it's not clear why that would fully prevent spurious transcription. Please reference an experimental test that demonstrates that it does.

"This spatial insulation drastically reduces the probability that RNA polymerase will engage the DNA during these brief accessibility events."

To zero percent? How much? Data please.

"Lack of strong sequence conservation does not preclude function"

Nobody says it precludes it. It is nevertheless evidence on the side of the scale for non-function over function.

"Similarly, short RNA half-life reflects a design for transient, context-dependent regulation, enabling rapid response to stimuli and precise temporal and spatial control, rather than indicating transcriptional noise."

Cool story bro. Please cite the experimental work that shows the "rapid-response, precise temporal-spatial control" functions of these extremely short-lived transcripts. What function did they accomplish? Sure sounds fancily technical but I'm strongly suspecting you're just storytelling. Evidence, got any?

Enhancer RNAs (eRNAs) are a well-established example of functional non-coding RNAs that exhibit rapid-response, precise temporal and spatial regulation. eRNAs are transcribed from active enhancers in a stimulus- or cell type-specific manner, and their expression often precedes or coincides with activation of nearby target genes, demonstrating tight temporal control. Despite their short half-lives and low abundance, eRNAs facilitate critical regulatory functions, including enhancer-promoter looping, recruitment of transcriptional co-activators such as Mediator, and modulation of chromatin accessibility, which require precise spatial localization near their sites of transcription. Importantly, many eRNAs show poor sequence conservation, indicating that their function relies more on transcriptional activity and genomic context than on primary sequence. Collectively, these features illustrate that rapid turnover, low abundance, and poor conservation do not indicate “junk” RNA, but rather are consistent with dynamic, functional regulatory roles.

Reference:

Sartorelli, V., & Lauberth, S. M. (2020). Enhancer RNAs are an important regulatory layer of the epigenome. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, 27(6), 521–528. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41594-020-0446-0

Why I am not surprised that suddenly the term "design" shows up

Hello Mehrshad, thanks for finally logging in.

Nevertheless, that was a review article on lncRNA and enhancers, not what I asked for specifically. I can't be bothered looking through the hundreds of references in that paper to try to guess which one might have the specific evidence (the experiments and the data they produce) I asked you for.

Optimized Quantitative Assessment of Enhancer RNA Stability in Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells

Jiin Moon et al. J Vis Exp. 2025.

I don't have full access to that paper, but from what I can gather it simply seems to show eRNA turnover rates in mouse embryonic stemcells. It's far from clear to me that this shows that "short RNA half-life reflects a design for transient, context-dependent regulation, enabling rapid response to stimuli and precise temporal and spatial control" for any purported lncRNA genes. Much less is it clear they are showing any pervasive function for poorly conserved, low-level transcripts.

I think you just told us stories.

For no particular reason, I thought I'd remind everybody of a logical fallacy known as ad hoc rescue or ad hoc hypothesis.

"In science and philosophy, an ad hoc hypothesis is a hypothesis added to a theory in order to save it from being falsified."

"Scientists are often skeptical of theories that rely on frequent, unsupported adjustments to sustain them. This is because, if a theorist so chooses, there is no limit to the number of ad hoc hypotheses that they could add. Thus the theory becomes more and more complex, but is never falsified. This is often at a cost to the theory's predictive power, however."

Ad hoc hypothesis

"Very often we desperately want to be right and hold on to certain beliefs, despite any evidence presented to the contrary. As a result, we begin to make up excuses as to why our belief could still be true, and is still true, despite the fact that we have no real evidence for what we are making up."

Ad hoc Rescue

"Ad hoc rescue (or fallacy) is a flawed tactic where someone creates a new, often baseless, explanation or excuse to protect a cherished belief or theory from being disproven by contradictory evidence, essentially "making it up on the spot" to save the original idea, rather than accepting error or offering real support. It's a way to defend a position by adding unsupported assumptions, like saying leprechauns are invisible to explain why no one sees them." (Google AI)

Just as a footnote, the evidence behind the recent increase in lncRNA is from this (currently) BioRxiv paper on long-read sequencing from the GENCODE consortium: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39554180/

It is also the analysis that has lead to the massive expansion in alternative transcripts in coding genes in this release and what will be GENCODE v50. The results of the analysis affect both human and mouse gene sets.

Couple of interesting claims in the abstract, and I wonder if they're true. "Novel gene annotations display evolutionary constraints, have well-formed promoter regions, and link to phenotype-associated genetic variants." And "Crucially, our targeted design assigned human-mouse orthologs at a rate beyond previous studies, tripling the number of human disease-associated lncRNAs with mouse orthologs."

@Michael Tress: That''s a preprint from October 2024. It still hasn't been published as far as I can tell.

It looks to me like GENCODE is just annotating transcripts. It seems unlikely that they have uncovered publications demonstrating function for tens of thousands of non-coding genes.

Mudge, J.M. et al. (2025) GENCODE 2025: reference gene annotation for human and mouse. Nucleic acids research 53:D966-D975. [doi: 10.1093/nar/gkae1078]

That is correct. GENCODE have annotated all these transcripts on the back of the analysis that I referenced. There is reliable evidence for all these coding and non-coding transcripts from long-read sequencing and GENCODE annotates evidence-based transcripts. This is a huge undertaking and GENCODE are not making much functional inference beyond recording the transcription, though we have validated peptides for a few novel coding genes.

The paper is not officially published, but I guess it will be sooner rather than later, at some point early to mid 2026.

"This is a huge undertaking and GENCODE are not making much functional inference beyond recording the transcription"

I find that statement hard to reconcile with the claims made in the abstract you linked, the claims I noted above. Please explain.

I am not sure whether these exact statements will be in the final abstract. But the claims are largely to do with the quality of the analysis (these lncRNA transcripts seem to be better supported than previously annotated models) and the sheer numbers of transcripts detected for human and mouse. For example, the lncRNA catalogue has expanded so much here (both in human and mouse) that it is unsurprising that it links many more disease-associated lncRNAs to mouse orthologs.

The new lncRNAs do appear to have greater conservation than both decoys and the previously annotated lncRNAs, though it is still low compared to coding genes. Still, this does suggest that at least proportion of these novel lncRNA transcripts may be functional one way or another.

I think I did, above. And if you go to the bioRxiv website you can look at the paper as it was originally.

But the point I am making is that GENCODE annotators annotate transcripts based on transcription evidence, not functionality. The authors of the paper have provided evidence for transcription. The transcripts have been annotated by GENCODE because they are expressed, not because they are functional. They may be functional, but that is not the reason they are annotated.

Now, what is written in the paper is an entirely different matter. Beyond the detection of the new transcripts. the authors have also carried out bulk analyses of the new transcripts. It is suggested that these newly annotated transcripts may have relatively more functional importance than those lncRNA that are already annotated.

"It is suggested that these newly annotated transcripts may have relatively more functional importance than those lncRNA that are already annotated."

Who suggested it and why? Does that mean that the lncRNAs that are already annotate are not functional?

OK, you will have to read the paper because I am not going into detail here.

This paper has lead to the addition of (approx.) another 130,000 lncRNA transcripts in human and not many fewer in mouse. Suffice to say that there are multiple indicators from that data that suggest that a higher proportion of the new cohort of long read sequencing derived lncRNA may be functional compared to the lncRNAs already annotated.

And no, it doesn't mean the lncRNAs already annotated are not functional. It remains the case that for the vast majority of lncRNA genes/transcripts we have no idea whether they are functional or not.

@Michael Tress: We all agree that GENCODE has identified transcripts that they refer to as lncRNAs. That's not the problem.

The problem is that they assume these transcripts come from genes. Here's what they say in the abstract, "Altogether 17,931 novel human genes (140,268 novel transcripts) and 22,784 novel mouse genes (136,169 novel transcripts) have been added to the GENCODE catalog ..."

The authors don't tell us their definition of a gene and they don't tell us what criteria they used to distinguish between genuine genes and spurious transcripts. It's true that they give us a hint when they discuss sequence conservation but the average reader (like me) can't figure out the data. It seems like their new algorithms detect more conservation than previous attempts but it also seems clear that only a subset of their new "genes" show some low level of conservation.

What about the non-conserved transcripts that they classify as genes?

If you read the discussion it looks like the authors are confused about the difference between annotating transcripts and calling them genes. I'm disappointed that they never comes to grips with the possibility that many of these transcripts are spurious and they never discuss how to tell the difference between real genes and junk RNA.

It's curious that they reference John Mattick (ref #52) but they don't reference this paper.

Ponting, C.P. and Haerty, W. (2022) Genome-Wide Analysis of Human Long Noncoding RNAs: A Provocative Review. Annual review of genomics and human genetics 23:153-172. [doi : 10.1146/annurev-genom-112921-123710]

Do long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) contribute little or substantively to human biology? To address how lncRNA loci and their transcripts, structures, interactions, and functions contribute to human traits and disease, we adopt a genome-wide perspective. We intend to provoke alternative interpretation of questionable evidence and thorough inquiry into unsubstantiated claims. We discuss pitfalls of lncRNA experimental and computational methods as well as opposing interpretations of their results. The majority of evidence, we argue, indicates that most lncRNA transcript models reflect transcriptional noise or provide minor regulatory roles, leaving relatively few human lncRNAs that contribute centrally to human development, physiology, or behavior. These important few tend to be spliced and better conserved but lack a simple syntax relating sequence to structure and mechanism, and so resist simple categorization. This genome-wide view should help investigators prioritize individual lncRNAs based on their likely contribution to human biology.

I suspect Mehrshad's comments are from an LLM.

Hi Larry,

Well, it is standard practice in gene annotation to group related transcripts together under the umbrella definition of a single gene. This is generally fairly simple for protein coding genes (read-through "genes" excepted), but defining genes around lncRNA transcripts can be quite complex. So, all the newly detected lncRNA transcripts will belong to a gene, though some of them will map to exisiting lncRNA genes.

If it is not clear from the abstract that the authors have detected the expression of transcripts and then grouped these transcripts into genes, it should certainly be made more obvious. And it ought to be made clear that almost all of the newly annotated genes from this paper are lncRNA genes if it isn't already.

As you said the conservation levels are still low even with the apparent increased conservation of the new transcripts. But I don't think that the analysis is showing that LncRNA is suddenly much more important than we thought, just that the new transcripts detected by long read sequencing are probably overall higher quality transcripts than were there previously.

As for the reference, I am not surprised that the authors did not use Ponting and Haerty. After you have carried out all that work to detect and carefully check the quality of hundreds of thousands of new transcripts in human and mice, you are hardly likely to refer to a paper that claims that "most lncRNA transcript models reflect transcriptional noise".

In any case, these new lncRNA transcripts are a step forward because they will provide opportunities to test theories about how many are likely to be functional.

@Michael Tress says, "In any case, these new lncRNA transcripts are a step forward because they will provide opportunities to test theories about how many are likely to be functional."

But the authors have already decided that they are functional because they declare that the transcripts come from genes. And lots of other scientists are using the GENCODE annotation to look at other features of "genes": for example, several groups are trying to define promoters and regulatory sequences by assuming that all of the lnc "gene" promoters are genuine biologically relevant promoters.

Other scientists and science writers are using the GENCODE definition to declare a revolution in our understanding of biology because we now know that there are more non-coding genes than coding genes. Still other scientists are using it to "overthrow" our understanding of molecular evolution because large segments of our genome are functional but not conserved and not under purifying selection.

The GENCODE decision has consequences. That's why they should have been more careful.

As for the missing Ponting and Haerty reference, I was taught that scientists are supposed to address all data that might conflict with their hypothesis. I thought this was supposed to be standard practice.

Details that could throw doubt on your interpretation must be given, if you know them. You must do the best you can — if you know anything at all wrong, or possibly wrong — to explain it. If you make a theory, for example, and advertise it, or put it out, then you must also put down all the facts that disagree with it, as well as those that agree with it.

Richard Feynman in "Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman": Adventures of a Curious Character.

The remit of GENCODE is to annotate all evidence-based features in the human and mouse genomes. So, new transcripts are only annotated when there is evidence for their expression.

Since this large-scale GENCODE-based analysis has provided evidence from tissues for hundreds of thousands of novel transcripts, they are annotated by GENCODE.

Novel transcripts are always defined within genes. It is a technical decision. The numbers of lncRNA genes has risen substantially because many of the novel lncRNA transcripts fell outside of previously annotated lncRNA genes.

(At the same time, GENCODE have also annotated hundreds of thousands of novel alternative transcripts for protein coding genes based on this analysis, but almost all are within currently defined coding genes, so not many novel coding genes have been added.)

What GENCODE cannot do (based on its remit) when it detects evidence for hundreds and thousands of novel lncRNA and protein transcripts is decide not to annotate them because they might not be functional enough.

Transcripts annotated in Ensembl/GENCODE are there because there is evidence for their expression.

Yes, there are plenty of interested scientists out there, but the large numbers of novel sequences found in long-read sequencing analyses is a reality, so this data would have been used with or without any GENCODE annotation.

@Michael Tress: You and your colleagues at GENCODE have characterized and annotated regions of the human genome that are transcribed. Nobody really objects to that part of your work although some of us wonder whether it's worth the expense and effort. (Maybe it's time to stop?)

However, many us object strongly to your decision to call these transcribed regions "genes" without providing evidence of function or making it clear that you are using a non-standard definition of "gene" that probably includes spurious transcription.

These objections have been raised repeatedly over the past two decades and I find it puzzling and annoying that you have not addressed them. Do you have an explanation?

Can you give me, right now, the definition of "gene" that you are using - the one that allows you to declare that there are more than 35,000 lncRNA genes in the human genome?

All this reminds me of a valuable lesson taught by remote sensing. I once watched a tv programme about a group of archaeologists digging an ancient Egyptian site north of Cairo. In order to identify the size and shape of the structures they were digging, they used a new technique - airborne Lidar (laser imaging, detection, and ranging). It was very successful in showing the shape and extent of the structures, and surrounding structures. The group then used the technique over a large area and claimed the results found hundreds of new archaeological sites. Except they hadn't. We were taught that remote sensing will provide results based on the algorithm used to analyze the data. It produces TARGETS, potential finds, not examples of what you are looking for. To confirm what has been found is what you think it is, you need to GROUND TRUTH it. Boots on the ground, go there and confirm what has been found. That is where the hard work begins. That's what the Archaeologists failed to do, and hence could not differentiate true archaeological structures from modern ones in the data.

Which brings us to GENCODE. They have identified thousands of TARGETS, not genes. What they need to do now is CELL TRUTH it. Show that the targets do have a function and conform to a reasonable definition of a gene, and are not spurious transcriptions or produce things that are rapidly degraded by the cell. Unfortunately, that is where the hard work begins.

Well said. The data produced by GENCODE is certainly useful as a springboard to decide where to start looking for potentially functional genes. It is the first step in that process, but it is a far cry from having even remotely substantiated that they are, in fact, functional genes.

Agree with Chris and Mikkel, and as far as I can see the only substantial difference I have with Larry is the use of the word "gene". Unfortunately or not, I think that ship has sailed. Gene has been used by annotators for collections of lncRNAtranscripts, with or without attached known functions for ten years or so. Unless you can convince the people who work with RNA to walk it back somehow, there is not much to be done.

So, anyway, here's the Ensembl definition of a gene "Genomic locus where transcription occurs. A gene may have one or more transcripts, which may or may not encode proteins."

The RefSeq definition is a bit harder to pin down, but the NIH website says this "A more expansive definition of a gene includes those segments of DNA that encode information for making an RNA molecule that functions in some fashion other than directly coding for a protein; these are sometimes referred to as RNA genes." and admits "The exact definition of the word gene has long been a source of scientific debate."

It's not just lncRNA "genes" either, there are plenty of predicted protein coding transcripts in genes that are almost certainly not functional either, but they be referred to as coding genes until proven otherwise (i.e. more or less forever).

As a PS, originally annotators used loci to describe a collection of lncRNA transcripts.

The change to using lncRNA gene instead of locus seems to have started in 2010 with a number of papers from the Lipovich group. Interested databases such as LncVar and Lncipedia (really) jumped on board from 2013/2014 onwards.

GENCODE started referring to lncRNA loci as genes in this 2012 Genome Research paper "The GENCODE v7 catalog of human long noncoding RNAs: analysis of their gene structure, evolution, and expression". Oddly enough, Leonard Lipovich was a co-author.

@Michael Tress: You and your GENCODE/ENCODE colleagues are free to make up a definition of gene that conforms to your biases. However you know full well that your definition conflicts with the common textbook definition requiring that the gene transcript must have a function. You know, or should know, that many scientists do not agree with your definition because it includes junk DNA sequences that are transcribed by accident.

You have an obligation to declare and explain your definition in all your publications and point out to your readers that it differs from another common definition. You have an obligation to make it clear to your readers that you do not distinguish between functional transcripts and spurious transcripts.

You can't skip over that scientific obligation just because you think "that ship has sailed" when what you really mean is that a small group of scientists has convinced themselves that they can use a non-standard definition just because they've been doing it for many years.

I may not be able to convince you to "walk back" your definition but I hope to at least convince you to be honest about stating it clearly in your papers and pointing out how it differs from another common definition that includes function.

Hi Larry,

I understand where you are coming from, and it would be great if we could get everyone not to change the meaning of words, but meanings do evolve even if we don't want them to. Here's another example, try explaining to a most RNA/computer scientists that "isoform" was not invented so they don't have to say "alternative transcript", and all you will get is a blank look. Or they might suggest using "transcript isoform" instead.

In these cases one can insist on the correct use of words if refereeing a paper, but once misuse has become commonplace you might as well be King Canute attempting to stop the waves.

The misuse of "isoform" has gone too far now, but maybe its not too late to revert the change in use of "gene". It's only been 12 years. Maybe someone can start a media campaign involving important scientists to revert to the original meaning. Perhaps a start would be leaving a comment on the BioRxiv paper before it is published - pre-publication to a certain extent is a way of allowing everyone to referee a paper.

One thing that I would advise is to stop making this conversation quite so personal. This is not my definition of a gene. I am not advocating this use of the word gene. Nothing I do will change what Ensembl thinks is the definition of the word gene.

GENCODE has not been part of ENCODE for well over a decade (despite the similarity of the name) and I am no longer part of GENCODE (despite appearing as an author in this paper).

In any case, I will repeat that the paper is a really impressive technical achievement, which I only mentioned because you asked where all the new lncRNA had come from. I only had a small role in the paper, related to protein coding genes not lncRNA.

@Michael Tress: Your name is on several GENCODE papers that use the word "gene" in a non-standard way. I simply assumed that as an author you take responsibility for every paper you publish.

And let's be clear about one thing. The definition of "gene" has not changed. There are no textbooks that now define a gene as any DNA sequence that's transcribed even if the RNA has no function.

Some people, for various reasons, may have a different understanding of "gene" but that doesn't mean they have succeeded in changing the consensus definition. It just means that they don't understand the problem.

I also have a problem with using "alternative splicing" for transcripts that may simply be splicing errors.

The term "lncRNA" is also a problem since it's come to imply a special kind of functional RNA. It would be better to just call them transcripts; that way you aren't tempted to refer to the transcribed DNA as "transcript genes."

Hi Larry. Yes, I am on several of the annual GENCODE consortium update papers that use the word gene in the way you are not fond of. It’s not my part of the paper, our section has nothing to do with LncRNA, and I really don’t have strong opinions about the use of gene in this way.

It doesn’t seem like anyone else is too upset about this use of the word either because I don’t see any comments on the BiorXiv paper web page.

No, the initial definition of gene hasn’t changed and I apologise if I gave the impression that I thought that. What has changed (is changing?) is its use. There are now more than 800 papers in PubMed that use one form or other of the word “LncRNA gene(s)” in their abstract. By way of comparison ”LncRNA locus/loci” was used just 140 times. “LncRNA” on its own is a lot more common, but gene is clearly preferred to locus when referring to collections of LncRNA transcripts.

Again, I am not arguing that this use of "gene" is right, I am just providing data.

Post a Comment