It's theoretically possible that the presence of abundant transposon fragments in a genome could provide a clade with a selective advantage at the level of species sorting. Is this an important contribution to the junk DNA debate?

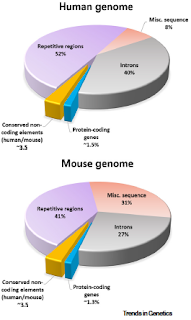

As I explained in Function Wars Part IX, we need to maintain a certain perspective in these debates over function. The big picture view is that 90% of the human genome qualifies as junk DNA by any reasonable criteria. There's lots of evidence to support that claim but in spite of the evidence it is not accepted by most scientists.

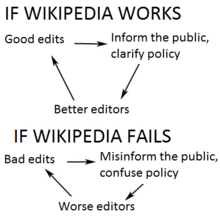

Most scientists think that junk DNA is almost an oxymoron since natural selection would have eliminated it by now. Many scientists think that most of our genome must be functional because it is transcribed and because it's full of transcription factor binding sites. My goal is to show that their lack of understanding of population genetics and basic biochemistry has led them astray. I am trying to correct misunderstandings and the false history of the field that have become prominent in the scientific literature.

For the most part, philosophers and their friends have a different goal. They are interested in epistemology and in defining exactly what you mean by 'function' and 'junk.' To some extent, this is nitpicking and it undermines my goal by lending support, however oblique, to opponents of junk DNA.1

As I've mentioned before, this is most obvious when it comes to the ENCODE publicity campaign of 2012 [see: Revising history and defending ENCODE]. The reason why the ENCODE researchers were wrong is that they didn't understand that many transcription factor binding sites are unimportant and they didn't understand that many transcripts could be accidental. These facts are explained in the best undergraduate textbooks and they were made clear to ENCODE researchers in 2007 when they published their preliminary results. They were wrong because they didn't understand basic biochemistry. [ENCODE 2007]

Some people are trying to excuse ENCODE on the grounds that they simply picked an inappropriate definition of function. In other words, ENCODE made an epistemology error not a stupid biochemistry mistake. Here's another example from a new paper by Ford Doolittle in Biology and Philosophy. He says,

However, almost all of these developments in evolutionary biology and philosophy passed molecular genetics and genomics by, so that publicizers of the ENCODE project’s results could claim in 2012 that 80.4% of the human genome is “functional” (Ecker et al 2012) without any well thought-out position on the meaning of ‘function’. The default assumption made by ENCODE investigators seemed to have been that detectable activities are almost always products of selection and that selection almost always serves the survival and reproductive interests of organisms. But what ENCODE interpreted as functionality was unclear—from a philosophical perspective. Charitably, ENCODE’s principle mistake could have been a too broad and level-ignorant reading of selected effect (SE) “function” (Garson 2021) rather than the conflation of SE and causal role (CR) definitions of “the F-word”, as it is often seen as being (Doolittle and Brunet 2017).

My position is that this is far too "charitable." ENCODE's mistake was not in using the wrong definition of function; their mistake was in assuming that all transcripts and all transcription factor binding sites were functional in any way. That was a stupid assumption and they should have known better. They should have learned from the criticism they got in 2007.

This is only a small part of Doolittle's paper but I wanted to get that off my chest before delving into the main points. I find it extremely annoying that there's so much ink and electrons being wasted on the function wars when the really important issues are a lack of understanding of population genetics and basic biochemistry. I fear that the function wars are contributing to the existing confusion rather than clarifying it.

Doolittle, F. (2022) All about levels: transposable elements as selfish DNAs and drivers of evolution. Biology & Philosophy 37: article number 24 [doi: 10.1007/s10539-022-09852-3]

The origin and prevalence of transposable elements (TEs) may best be understood as resulting from “selfish” evolutionary processes at the within-genome level, with relevant populations being all members of the same TE family or all potentially mobile DNAs in a species. But the maintenance of families of TEs as evolutionary drivers, if taken as a consequence of selection, might be better understood as a consequence of selection at the level of species or higher, with the relevant populations being species or ecosystems varying in their possession of TEs. In 2015, Brunet and Doolittle (Genome Biol Evol 7: 2445–2457) made the case for legitimizing (though not proving) claims for an evolutionary role for TEs by recasting such claims as being about species selection. Here I further develop this “how possibly” argument. I note that with a forgivingly broad construal of evolution by natural selection (ENS) we might come to appreciate many aspects of Life on earth as its products, and TEs as—possibly—contributors to the success of Life by selection at several levels of a biological hierarchy. Thinking broadly makes this proposition a testable (albeit extraordinarily difficult-to-test) Darwinian one.

The essence of Ford's argument builds on the idea that active transposable elements (TEs) are examples of selfish DNA that propagate in the genome. This is selection at the level of DNA. Other elements of the genome, such as genes, regulatory sequences, and origins of replication, are examples of selection at the level of the organism and individuals within a population. Ford points out that some transposon-related sequences might be co-opted to form functional regions of the genome that are under purifying selection at the level of organisms and populations. He then goes on to argue that species with large amounts of transposon-related sequences in their genomes might have an evolutionary advantage because they have more raw material to work with in evolving new functions. If this is true, then this would be an example of species level selection.

These points are summarized near the end of his paper.

Thus TE families, originating and establishing themselves abundantly within a species through selection at their own level may wind up as a few relics retained by purifying selection at the level of organisms. Moreover, if this contribution to the formation of useful relics facilitated the diversification of species or the persistence of clades, then we might also say that these TE families were once “drivers” of evolution at these higher levels, and that their possession was once an adaptation at each such higher level.

There are lots of details that we could get into later but I want to deal with the main speculation; namely, that species with lots of TE fragments in their genome might have an adaptive advantage over species that don't.

This is challenging topic because lots of people have expressed their opinions on many of the topics that Ford covers in his article. None of their opinions are identical and many of them are based on different assumptions about things like evolvability, teleology, the significance of the problem, how to define species sorting, and whether hierachy theory is important . Many of those people are very smart (as is Ford Doolittle) and it hurts my brain trying to figure out who is correct. I'll try and explain some of the issues and the controversies.

A solution in search of a problem?

What's the reason for speculating that abundant bits of junk DNA might be selected because they will benefit the species at some time in the next ten million years or so? Is there a problem that this speculation explains?

The standard practice in science is to suggest hypotheses that account for an unexplained observation; for example, the idea of abundant junk DNA explained the C-value Paradox and the mutation load problem. Models are supposed to have explanatory power—they are supposed to explain something that we don't understand.

Ford thinks there's is a reason for retaining junk DNA. He writes,

Eukaryotes are but one of the many clades emerging from the prokaryotic divergence. Although such beliefs may be impossible to support empirically it is widely held that that was a special and evolutionarily important event....

Assuming this to be true (but see Booth and Doolittle 2015) we might ask if there are reasons for this differential evolutionary success, and are these reasons clade- level properties that have been selected for at this high level? Is one of them the possession of large and variable families of TEs?

You'll have to read his entire paper to see his full explanation but this is the important part. Ford, thinks that the diversity and success of eukaryotes requires an explanation because it can't be accounted for by standard evolutionary theory. I don't see the problem so I don't see the need for an explanation.

Of course there doesn't have to be a scientific problem that needs solving. This could just be a theoretical argument showing that excess DNA could lead to species level selection. That puts it more in the realm of philosophy and Ford does make the point in his paper that one of his goals is simply to defend multilevel selection theory (MLST) as a distinct possibility. The main proponents of this idea (Hierarchy Theory) are Niles Eldredge and Stephen Jay Gould and the theory is thoroughly covered in Gould's book The Structure of Evolutionary Theory. I was surprised to discover that this book isn't mentioned in the Doolittle paper.

I don't have a problem with Hierarchy Theory (or Multilevel Selection Theory, or group selection) as a theoretical possibility. The important question, as far as I'm concerned, is whether there's any evidence to support species selection. As Ford notes, "such beliefs may be impossible to support empirically" and that may be true; however, there's a danger in promoting ideas that have no empirical support because that opens a huge can of worms that less rigorous scientists are eager to exploit.

With respect to the role of transposon-related sequences, the important question, in my opinion, is: Would life look substantially less diverse or less complex if no transposon-related sequences had ever been exapted to form elements that are now under purifying selection? I suspect that the answer is no—life would be different but no less diverse or complex.

Species selection vs species sorting

Speculations about species-level evolution are usually discussed in the context of group selection and species selection or, more broadly, as the levels-of-selection debate. Those are the terms Doolittle uses and he is very much interested in explaining junk DNA as contributing to adaptation at the species level.

But if the insertion of [transcription factor binding sites] TFBSs helps species to innovate and thus diversify (speciate and/or forestall extinction) and is a consequence of TFBS-bearing TE carriage, then such carriage might be cast as an adaptation at the level of species and maintained at that level too, by the differential extinction of TE-deficient species (Linquist et al 2020; Brunet et al 2021).

I think it's unfortunate that we don't use the term 'species sorting' instead of 'species selection' because as soon as you restrict your discussion to selection, you are falling into the adaptationist trap. Elisabeth Vrba, backed by Niles Eldredge, preferred 'species sorting' partly in order to avoid this trap.

I am convinced, on the basis of Vrba's analysis, that we naturalists have been saying 'species selection' when we really should have been calling the phenomenon 'species sorting.' Species sorting is extremely common, and underlies a great deal of evolutionary patterns, as I shall make clear in this narrative. On the other hand, true species selection, in its properly more restricted sense, I now believe to be relatively rare. (Niles Eldredge, in Reinventing Darwin (1995) p. 137)

As I understand it, the difference between 'species sorting' and 'species selection' is that the former term does not commit you to an adaptationist explanation.2 Take the Galapagos finches as an example. There has been fairly rapid radiation of these species from a small initial population that reached the islands. This radiation was not due to any intrinsic propery of the finch genome that made finches more successful at speciation; it was just a lucky accident. Similary, the fact that there are many marsupial species in Australia is probably not because the marsupial genome is better suited to evolution; it's probably just a founder effect at the species level.

Gould still prefers 'species selection' but he recognizes the problem. He points out that whenever you view species as evolving entities within a larger 'population' of other species, you must consider species drift as a distinct possibility. And this means that you can get evolution via a species-level founder effect that has nothing to do with adapation.

Low population (number of species in a clade) provides the enabling criterion for important drift ... at the species level. The analogue of genetic drift—which I shall call 'species drift' must act both frequently and powerfully in macroevolution. Most clades do not contain large numbers of species. Therefore, trends may often originate for effectively random reasons. (Stephen J. Gould, in The Structure of Eolutionary Theory (2001) p. 736)

Let's speculate how this might relate to the current debate. It's possible that the apparent diversity and complexity of large multicellular eukaryotes is mostly due to the fact that they have small populations and long generation times. This means that there were plenty of opportunities for small isolated populations to evolve distinctive features. Thus, we have, for example, more than 1000 different species of bats because of species drift (not species selection). What this means is that the evolution of new species is due to the same reason (small populations) as the evolution of junk DNA. One phenomenon (junk DNA) didn't cause the other (speciation); instead, both phenomena have the same cause.

Michael Lynch has written about this several times, but the important, and mind-hurting, paper is Lynch (2007) where he says,

Under this view, the reductions in Ng that likely accompanied both the origin of eukaryotes and the emergence of the animal and land-plant lineages may have played pivotal roles in the origin of modular gene architectures on which further develomental complexity was built.

Lynch's point is that we should not rule out nonadaptive processes (species drift) in the evolution of complexity, modularity, and evolvability.

If we used species sorting instead of species selection, it would encourage a more pluralsitic perspective and a wider variety of speculations. I don't mean to imply that this issue is ignored by Ford Doolittle, only that it doesn't get the attention it deserves.

Evolvability and teleology

Ford is invoking evolvability as the solution to the evolved complexity and diversity of multicellular eukaryotes. This is not a new idea: it is promoted by James Shapiro, by Mark Kirschner and John Gerhart, and by Günter Wagner, among others. (None of them are referenced in the Doolittle paper.)

The idea here is that clades with lots of TEs should be more successful than those with less junk DNA. It would be nice to have some data the address this question. For example, is the success of the bat clade due to more transposons than other mammals? Probably not, since bats have smaller genomes than other mammals. What about birds? There are lots of bird species but birds seem to have smaller genomes than some of their reptilian ancestors.

There are dozens of Drosophila species and they all have smaller genome sizes than many other flies. In this case, it looks like the small genome had an advantage in evolvability but that's not the prediction.

The concept of evolvability is so attractive that even a staunch gene-centric adaptationist like Richard Dawkins is willing to consider it (Dawkins, 1988). Gould devotes many pages (of course) to the subject in his big Structure book. Both Dawkins and Gould recognize that they are possibly running afoul of teleology in the sense of arguing that species have foresight. Here's how Dawkins puts it ...

It is all too easy for this kind of argument to be used loosely and unrespectably. Sydney Brenner justly ridiculed the idea of foresight in evolution, specifically the notion that a molecule, useless to a lineage of organisms in it own geological era, might nevertheless be retained in the gene pool because of its possible usefulness in some future era: "It might come in handy in the Cretaceous!" I hope I shall not be taken as saying anything like that. We certainly should have no truck with suggestions that individual animals might forego their selfish advantage because of posssible long-term benefits to their species. Evolution has no foresight. But with hindsight, those evolutionary changes in embryology that look as though they were planned with foresight are the ones that dominate successful forms of life.

I interpret this to mean that we should not be fooled by hindsight into looking for causes when what we are seeing is historical contingency. If you have not already read Wonderful Life by Stephen Jay Gould then I highly recommend that you get a copy and read it now in order to understand the role of contingency in the evolution of animals. You should also brush up on the more recent contributions to the tape-of-life debate in order to put this discussion about evolvability into the proper context [Replaying life's tape].

Ford also recognizes the teleological problem and even quotes Sydney Brenner! Here's how Ford explains the relationship between transposon-related sequences and species selection.

As I argue here, organisms took on the burden of TEs not because TE accumulation, TE activity or TE diversity are selected-for traits within any species, serving some current or future need, but because lower-level (intragenomic) selection creates and proliferates TEs as selfish elements. But also, and just possibly, species in which this has happened speciate more often or last longer and (even more speculatively still) ecosystems including such species are better at surviving through time, and especially through the periodic mass extinctions to which this planet has been subjected (Brunet and Doolittle 2015). ‘More speculatively still’ because the adaptations at higher levels invoked are almost impossible to prove empirically. So what I present are again only ‘how possibly’, not ‘how actually’ arguments (Resnick 1991).

This is diving deeply into the domain of abstract thought that's not well-connected to scientific facts. As I mentioned above, I tend to look on these speculations as solutions looking for a problem. I would like to see more evidence that the properties of genomes endow certain species with more power to diversify than species with different genomic properties. Nevertheless, the idea of evolvability is not going away so let's see if Ford's view is reasonable.

As usual, Stephen Jay Gould has thought about this deeply and come up with some useful ideas. His argument is complicated but I'll try and explain it in simple terms. I'm relying mostly on the section called "Resolving the paradox of Evolvability and Defining the Exaptive Pool" in The Structure of Evolutionary Theory pages 1270-1295.

Gould argues that in Hierarchy Theory, the properties at each level of evolution must be restricted to that level. Thus, you can't have evolution at the level of DNA impinging on evolution at the level of the organism. For example, you can't have selection between transposons within a genome affecting evolution at the level of organisms and population. Similarly, selection at the level of organisms can't directly affect species sorting.

What this means in terms of genomes full of transposon-related sequences is the following. Evolution at the level of species involves sorting (or selection) between different species or clades. Each of these species have different properties that may or may not make them more prone to speciations but those properties are equivalent to mutations, or variation, at the level of organisms. Some species may have lots of transposon sequences in their genome and some may have less and this difference arises just by chance as do mutations. There is no foresight in generating mutations and there is no foresight in having different sized genomes.

During species sorting, the differences may confer some selective advantage so species with, say, more junk DNA are more likely to speciate but the differences arose by chance in the same sense that mutations arise by chance (i.e. with no foresight). For example, in Lenski's long-term evolution experiment, certain neutral mutations became fixed by chance so that new mutations arising in this background became adaptive [Contingency, selection, and the long-term evolution experiment]. Scientists and philosophers aren't concerned about whether those neutral mutations might have arisen specifically in order to potentiate future evolution.

Similarly, it is inappropriate to say that transposons, or pervasive transcription, or splicing errors, arose BECAUSE they encouraged evolution at the species level. Instead, as Dawkins said, those features just look with hindsight as though they were planned. They are fortuitous accidents of evolution.

Gould also makes the point, again, that we could just as easily be looking at species drift as species selection and we have to be careful not to resort to adaptive just-so stories in the absence of evidence for selection.

Here's how Gould describes his view of evolvability using the term "spandrel" to describe potentiating accidents.

Thus, Darwinians have always argued that mutational raw material must be generated by a process other than organismal selection, and must be "random" (in the crucal sense of undirected towards adaptive states) with respect to realized pathways of evolutionary change. Traits that confer evolvability upon species-individuals, but arise by selection upon organisms, provide a precise analog at the species level to the classical role of mutation at the organismal level. Because these traits of species evolvability arise by a different process (organismal selection), unrelated to the selective needs of species, they may emerge as the species level as "random" raw material, potentially utilizable as traits for species selection.

The phenotypic effects of mutation are, in exactly the same manner, spandrels at the organismal level—that is, nonadaptive and automatic manifestations at a higher level of different kinds of causes acting directly at a lower level. The exaptation of a small and beneficial subset of these spandrels virtually defines the process of natural selection. Why else do we so commonly refer to the theory of natural selection as as interplay of "chance" (for the spandrels of raw material in mutational variation) and "necessity" (for the locally predictable directions of selection towards adaptation). Similarly, species selection operates by exapting emergent spandrels from causal processes acting upon organisms.

This is a difficult concept to gasp so I urge interested readers to study the relevant chapter in Gould's book. The essence of his argument is that species sorting can only be understood at the level of species as individuals and the properties of species as the random variation upon which species sorting operates.

Michael Lynch is also skeptical about evolvability but for slightly different reasons (Lynch, 2007). Lynch is characteristically blunt about how he views anyone who disagrees with him. (I have been on the losing side of one of those disagreement and I still have the scars to prove it.)

Four of the major buzzwords in biology today are complexity, modularity, evolvability, and robustness, and it is often claimed that ill-defined mechanisms not previously appreciated by evolutionary biologists must be invoked to explain the existence of emergent properties that putatively enhance the long-term success of extant taxas. This stance is not very different from the intelligent-design philosophy of invoking unknown mechanisms to explain biodiversity.

This is harsh and somewhat unfair since nobody would accuse Ford Doolittle of ulterior motives. Lynch's point is that evolvability must be subjected to the same rigorous standards that he applies to population genetics. He questions the idea that "the ability to evolve itself is actively promoted by directional selection" and raises four objections.

- Evolvability doesn't meet the stringent conditions that a good hypothesis demands.

- It's not clear that the ability to evolve is necessarily advantageous.

- There's no evidence that differences between species are anything other than normal variation.

- "... comparative genomics provides no support for the idea that genome architectural changes have been promoted in multicellular lineages so as to enhance their ability to evolve.

Why transposon-related sequences?

One of the problems that occurred to me was why there was so much emphasis on transposon sequences. Don't the same arguments apply to pseudogenes, random duplications, and, especially, genome doublings? They do, but the paper appears to be part of a series that arose out of a 2018 meeting on Evolutionary Roles of Transposable Elements: The Science and Philosophy organized by Stefan Linquist and Ford Doolittle. That's why there's a focus on transposons. I assume that Ford could make the same case for other properties of large genomes such as pervasive transcription, spurious transcription binding sites, and splicing errors even if they had nothing to do with transposons.

Is this an attempt to justify junk?

I argue that genomes are sloppy and junk DNA accumulates just because it can. There's no ulterior motive in having a large genome full of junk and it's far more likely to be slightly deleterious than neutral. I believe that all the evidence points in that direction.

This is not a popular view. Most scientists want to believe that all that of excess DNA is there for a reason. If it doesn't have a direct functional role then, at the very least, it's preserved in the present because it allows for future evolution. The arguments promoted by Ford Doolittle in this article, and by others in related articles, tend to support those faulty views about the importance of junk DNA even though that wasn't the intent. Doolittle's case is much more sophisticated than the naive views of junk DNA opponents but, nevertheless, you can be sure that this paper will be referenced frequently by those opponents.

Normal evolution is hard enough but multilevel selection is even harder, especially for molecular biologists who would never think of reading The Structure of Evolutionary Theory, or any other book on evolution. That's why we have to be really careful to distinguish between effects that are adaptations for species sorting and effects that are fortuitous and irrelevant for higher level sorting.

Function Wars

(My personal view of the meaning of function is described at the end of Part V.)

1. The same issues about function come up in the debate over alternative splicing [Alternative splicing and evolution].

2. See Vrba and Gould (1986) for a detailed discussion of species sorting and species seletion and how it pertains to the hierarchical perspective.

Dawkins, R. (1988) The Evolution of Evolvability. Artifical Life, The proceedings of an Interdisciplinary Workshp on The Synthesis and Simulation of Living Systems held September 1987 in Los Alamos, New Mexico. C. G. Langton, Addison-Wesley Publishing Company: 201-220.

Lynch, M. (2007) The frailty of adaptive hypotheses for the origins of organismal complexity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104:8597-8604. [doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702207104

Vrba, E.S. and Gould, S.J. (1986) The hierarchical expansion of sorting and selection: sorting and selection cannot be equated. Paleobiology 12:217-228. [doi: 10.1017/S0094837300013671]