The first Star Wars movie was released on this day in 1977. I was living in Geneva, Switzerland at the time and I didn't get to see the movie until July or August.

More Recent Comments

Friday, May 25, 2012

Wednesday, May 23, 2012

Better Biochemistry: The Perfect Enzyme

The Biologic Institute is a "research" facility funded by The Discovery Institute of Seattle, WA (USA). From time to time they post articles on their website. A few years ago they posted the following article: Physicists Finding Perfection… in Biology.

I want to address one particular point in that article.

ERV picked up on this theme in a 2009 posting: Having your Ford Pinto and Crashing it Too. That posting seemed to concede the point that enzymes are perfect.

That's the issue I want to discuss.

I want to address one particular point in that article.

For decades enzymologists have recognized that certain enzymes are catalytically perfect—meaning that they process reactant molecules as rapidly as these molecules can reach them by diffusion. [1] That hinted at a principle of physical perfection in biology, but no one anticipated its breadth until recently.The point of the article is that some things in biology are "perfect" but this presents a problem for "Darwinism." According to the "scientists" at the Biologic Institute. perfection is beyond the reach of a "Darwinian mechanism." The fact that we observe perfection in biology is evidence for design.

ERV picked up on this theme in a 2009 posting: Having your Ford Pinto and Crashing it Too. That posting seemed to concede the point that enzymes are perfect.

That's the issue I want to discuss.

Flunk the IDiots

Casey Luskin recently offered advice on the The Top Three Flaws in Darwinian Evolution. [see The Top Three Flaws In Evolutionary Theory ] At the end of that post he referred readers to The College Student's Back-to-School Guide to Intelligent Design. This is a remarkable document. It's designed to teach students how to debate their professors and/or disguise their true beliefs in order to pass a class.

Why do the IDiots need such advice? It's because Intelligent Design Creationism is under attack from dogmatic professors who can't think critically and who don't have open minds. The opening section lists examples, such as ...

Why do the IDiots need such advice? It's because Intelligent Design Creationism is under attack from dogmatic professors who can't think critically and who don't have open minds. The opening section lists examples, such as ...

A professor of biochemistry and leading biochemistry textbook author at the University of Toronto stated that a major public research university “should never have admitted” students who support ID, and should “just flunk the lot of them and make room for smart students.”

Tuesday, May 22, 2012

Free/Cheap Textbooks for Students

Sean Caroll, the physicist, has a blog called Cosmic Variance on the Discover Magazine website.1

Yesterday Sean posted an article by a guest blogger, Marc Sher, a physicist who teaches introductory physics at the College of William and Mary. Marc Sher is promoting something called the nonprofit textbook movement [Guest Post: Marc Sher on the Nonprofit Textbook Movement].

Here's what he says ...

Yesterday Sean posted an article by a guest blogger, Marc Sher, a physicist who teaches introductory physics at the College of William and Mary. Marc Sher is promoting something called the nonprofit textbook movement [Guest Post: Marc Sher on the Nonprofit Textbook Movement].

Here's what he says ...

The textbook publishers’ price-gouging monopoly may be ending.Now, I usually think of myself as a socialist, so it's a little uncomfortable for me to be defending capitalism, but here goes.

For decades, college students have been exploited by publishers of introductory textbooks. The publishers charge about $200 for a textbook, and then every 3-4 years they make some minor cosmetic changes, reorder some of the problems, add a few new problems, and call it a “new edition”. They then take the previous edition out of print. The purpose, of course, is to destroy the used book market and to continue charging students exorbitant amounts of money.

Monday, May 21, 2012

Monday's Molecule #171

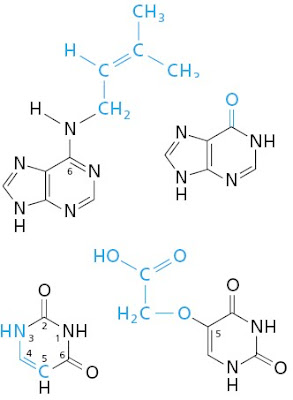

Today's molecule is four molecules. You need to correctly identify each one. Then you need to tell me whether each molecule (or a derivative) is found in living cells, and if so, where. That's a total of nine answers.

Post your answers as a comment. I'll hold off releasing any comments for 24 hours. The first one with the correct answers wins. I will only post mostly correct answers to avoid embarrassment. The winner will be treated to a free lunch with a very famous person, or me.

There could be two winners. If the first correct answer isn't from an undergraduate student then I'll select a second winner from those undergraduates who post the correct answer. You will need to identify yourself as an undergraduate in order to win. (Put "undergraduate" at the bottom of your comment.)

Some past winners are from distant lands so their chances of taking up my offer of a free lunch are slim. (That's why I can afford to do this!)

In order to win you must post your correct name. Anonymous and pseudoanonymous commenters can't win the free lunch.

Winners will have to contact me by email to arrange a lunch date.

Comments are invisible for 24 hours. Comments are now open.

UPDATE:The molecules are: N6-isopentyladenine, hypoxanthine, uridine, and 5-oxyacetic acid uridine. Uridine is found in all RNAs and the other three are found in various tRNA molecules.

There are no winners this week!!!

Winners

Nov. 2009: Jason Oakley, Alex Ling

Oct. 17: Bill Chaney, Roger Fan

Oct. 24: DK

Oct. 31: Joseph C. Somody

Nov. 7: Jason Oakley

Nov. 15: Thomas Ferraro, Vipulan Vigneswaran

Nov. 21: Vipulan Vigneswaran (honorary mention to Raul A. Félix de Sousa)

Nov. 28: Philip Rodger

Dec. 5: 凌嘉誠 (Alex Ling)

Dec. 12: Bill Chaney

Dec. 19: Joseph C. Somody

Jan. 9: Dima Klenchin

Jan. 23: David Schuller

Jan. 30: Peter Monaghan

Feb. 7: Thomas Ferraro, Charles Motraghi

Feb. 13: Joseph C. Somody

March 5: Albi Celaj

March 12: Bill Chaney, Raul A. Félix de Sousa

March 19: no winner

March 26: John Runnels, Raul A. Félix de Sousa

April 2: Sean Ridout

April 9: no winner

April 16: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

April 23: Dima Klenchin, Deena Allan

April 30: Sean Ridout

May 7: Matt McFarlane

May 14: no winner

May 21: no winner

Post your answers as a comment. I'll hold off releasing any comments for 24 hours. The first one with the correct answers wins. I will only post mostly correct answers to avoid embarrassment. The winner will be treated to a free lunch with a very famous person, or me.

There could be two winners. If the first correct answer isn't from an undergraduate student then I'll select a second winner from those undergraduates who post the correct answer. You will need to identify yourself as an undergraduate in order to win. (Put "undergraduate" at the bottom of your comment.)

Some past winners are from distant lands so their chances of taking up my offer of a free lunch are slim. (That's why I can afford to do this!)

In order to win you must post your correct name. Anonymous and pseudoanonymous commenters can't win the free lunch.

Winners will have to contact me by email to arrange a lunch date.

UPDATE:The molecules are: N6-isopentyladenine, hypoxanthine, uridine, and 5-oxyacetic acid uridine. Uridine is found in all RNAs and the other three are found in various tRNA molecules.

There are no winners this week!!!

Winners

Nov. 2009: Jason Oakley, Alex Ling

Oct. 17: Bill Chaney, Roger Fan

Oct. 24: DK

Oct. 31: Joseph C. Somody

Nov. 7: Jason Oakley

Nov. 15: Thomas Ferraro, Vipulan Vigneswaran

Nov. 21: Vipulan Vigneswaran (honorary mention to Raul A. Félix de Sousa)

Nov. 28: Philip Rodger

Dec. 5: 凌嘉誠 (Alex Ling)

Dec. 12: Bill Chaney

Dec. 19: Joseph C. Somody

Jan. 9: Dima Klenchin

Jan. 23: David Schuller

Jan. 30: Peter Monaghan

Feb. 7: Thomas Ferraro, Charles Motraghi

Feb. 13: Joseph C. Somody

March 5: Albi Celaj

March 12: Bill Chaney, Raul A. Félix de Sousa

March 19: no winner

March 26: John Runnels, Raul A. Félix de Sousa

April 2: Sean Ridout

April 9: no winner

April 16: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

April 23: Dima Klenchin, Deena Allan

April 30: Sean Ridout

May 7: Matt McFarlane

May 14: no winner

May 21: no winner

The Top Three Flaws In Evolutionary Theory

Casey Luskin is one of the leading IDiots of the Discovery Institute. He posts frequently on Evolution News & Views. Here's one of his recent posts where he lets us in one the The Top Three Flaws in Evolutionary Theory.

If you've ever wondered why I call them IDiots, this will help you understand.

If you've ever wondered why I call them IDiots, this will help you understand.

Unfortunately most public schools do NOT teach about the flaws in evolutionary theory. Instead, they censor this information, hiding from students all of the science that challenges Darwinian evolution. But in a perfect world, if the evidence against Darwinian theory were taught, these would be my top three choices:

- Tell students that the fossil record often lacks transitional forms and that there are "explosions" of new life forms, a pattern of radiations that challenges Darwinian evolutionary theory.

- Tell students that many scientists have challenged the ability of random mutation and natural selection to produce complex biological features.

- Tell students that many lines of evidence for Darwinian evolution and common descent are weak:

a. Vertebrate embryos start out developing very differently, in contrast with the drawings of embryos often found in textbooks which mostly appear similar.

b. DNA evidence paints conflicting pictures of the "tree of life". There is no such single "tree."

c. Evidence of small-scale changes, such as the modest changes in the size of finch-beaks or slight changes in the color frequencies in the wings of "peppered moths", shows microevolution, NOT macroevolution.

Sunday, May 20, 2012

Time to Re-write the Textbooks: RNA has a Fifth Base!!!

From Science Daily via a press release from NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center/Weill Cornell Medical College: RNA Modification Influences Thousands of Genes: Revolutionizes Understanding of Gene Expression.

Edmund BurkeWe've known about modified bases in DNA since the early 1970s so there aren't any modern textbooks that don't mention them. If your high school genetics course didn't mention modified bases it isn't because scientists didn't know of their existence—unless, of course, you graduated from high school more than forty years ago.

We've known about the presence of N6-methyladenosine in mRNA for several decades. Here's the introduction to a 1984 paper by Horowitz et al. (1984).

Not only that, textbooks also contain references to two other modified bases in mRNA. N7-methylguanylate is common in cap structures and several mRNAs are known to contain inosine (I), a modified form of adenylate.

I blame the science writers at Cornell Medical Center for writing something that is not true and I blame the authors of the paper for hype and exaggeration and for not correcting the press release before it was published. That's not how science is supposed to work.

Over the past decade, research in the field of epigenetics has revealed that chemically modified bases are abundant components of the human genome and has forced us to abandon the notion we've had since high school genetics that DNA consists of only four bases.Those who don't know history are destined to repeat it.

Now, researchers at Weill Cornell Medical College have made a discovery that once again forces us to rewrite our textbooks. This time, however, the findings pertain to RNA, which like DNA carries information about our genes and how they are expressed. The researchers have identified a novel base modification in RNA which they say will revolutionize our understanding of gene expression.

Their report, published May 17 in the journal Cell, shows that messenger RNA (mRNA), long thought to be a simple blueprint for protein production, is often chemically modified by addition of a methyl group to one of its bases, adenine. Although mRNA was thought to contain only four nucleobases, their discovery shows that a fifth base, N6-methyladenosine (m6A), pervades the transcriptome.

Edmund BurkeWe've known about modified bases in DNA since the early 1970s so there aren't any modern textbooks that don't mention them. If your high school genetics course didn't mention modified bases it isn't because scientists didn't know of their existence—unless, of course, you graduated from high school more than forty years ago.

We've known about the presence of N6-methyladenosine in mRNA for several decades. Here's the introduction to a 1984 paper by Horowitz et al. (1984).

The most prevalent internal methylated nucleoside in eukaryotic mRNA is N6-methyladenosine (m6A). This modified nucleoside is found in RNAs of higher eukaryotic organisms (1-6), plants (7-9), and viruses (3, 10-12), and occurs at two specific sequences: Gpm6ApC and Apm6ApC (13-17).Refereences 1-5 are from 1975 meaning that in the published scientific literature the presence of m6A dates back 37 years. That's more than enough time to make it into the textbooks. It's in the textbooks.

Not only that, textbooks also contain references to two other modified bases in mRNA. N7-methylguanylate is common in cap structures and several mRNAs are known to contain inosine (I), a modified form of adenylate.

I blame the science writers at Cornell Medical Center for writing something that is not true and I blame the authors of the paper for hype and exaggeration and for not correcting the press release before it was published. That's not how science is supposed to work.

[Hat Tip: Uncommon Descent: Is there a fifth base in RNA?]

Horowitz, S., Horowitz, A., Nilsen, T.W., Munns, T.W. and Rottman, F.M. (1984) Mapping of N6-methyladenosine residues in bovine prolactin mRNA. PNAS 81:5667-5671. [PDF]

Advice for High School Graduates

The Chicago Tribune has an opinion piece on Open letter to high school grads. You really should read the entire thing but here's part of it ...

If you haven't posted a good academic performance in high school, don't believe a university, its leadership, advertisements or admissions officers who co-sign your promissory note with no responsibility for its payment obligation. They need paying students.Who wrote this? It's Walter V. Wendler, who is listed as director of the School of Architecture and former chancellor at Southern Illinois University.

Stoking a deceitful dream on life support — an underappreciated, overfinanced, media-hyped charade — is the real deception, and the weight falls on your back, not theirs.

A shameful, elaborate sham, when one out of two college graduates this year are unemployable in their chosen field.

Look carefully at the costs and benefits of a university education. University officials may not tell you the truth: Enrollments could drop. Bankers will not tell you the truth: Interest income will fall off. Elected officials will not tell you the truth: Elections will be lost. Listen to those really concerned for you carefully.

Friday, May 18, 2012

On the Significance of Student Evaluations

I been interested in the efficacy of students evaluations for a long time [Student Evaluations] [Student Evaluations] [Student Evaluations Don't Mean Much].

I been interested in the efficacy of students evaluations for a long time [Student Evaluations] [Student Evaluations] [Student Evaluations Don't Mean Much]. There's an extensive pedagogical literature on the issue [Student Evaluations: A Critical Review] [New Research Casts Doubt on Value of Student Evaluations of Professors] [Does Professor Quality Matter? Evidence from Random Assignment of Students to Professors] [Evaluating Methods for Evaluating Instruction: The Case of Higher Education] [Of What Value are Student Evaluations?] [Why Student Evaluations of Teachers are Bullshit, Some Sources ].

Much of this literature points out what is obvious to any university instructor; students evaluations are not very good at measuring teaching effectiveness.

Thursday, May 17, 2012

All IDiots Believe in Evolution!

The title of this post may shock you but bear with me for a minute. I've been trying for years to educate creationists on the meaning of evolution and the strawman term "Darwinism." I've pointed out repeatedly that the the standard minimal definition of evolution ("Evolution is a process that results in heritable changes in a population spread over many generations") should be perfectly acceptable to any IDiot. They don't really reject all of evolution, just the part that causes particular problems for their religion.

Finally, we have an Intelligent Design Creationist who is willing to take the bull by the horns and point out the obvious. Johnnyb explains how his fellow IDiots should think about evolution [How to Talk to Your Professors About Your Darwin Doubts].

I'm willing to bet that the vast majority will still never admit that evolution, as defined, is a fact because we can directly observe it happening right before our eyes.

Finally, we have an Intelligent Design Creationist who is willing to take the bull by the horns and point out the obvious. Johnnyb explains how his fellow IDiots should think about evolution [How to Talk to Your Professors About Your Darwin Doubts].

So what is one to do? Well, thankfully, our friends the evolutionists have given us a way out. In their zeal to claim consensus on the “fact of evolution,” they have had to steamroll together such a large diversity of opinion into the single term “evolution”, that the word “evolution” no longer has the grand meaning it used to. The only real meaning everyone can agree on is “change in allele frequency over time” – and that is a definition that literally everyone can agree with.Let's see how many of his fellow creationists take this advice to heart. Are you listening Denyse?

In other words, even if you are a young earth creationist, if your professor asks if you believe in evolution, the legitimate answer is “yes”. Given the common definition of “evolution,” the only thing they are really asking with that question is, “do you believe in genetics?”

Therefore, here is how you can, and, I say, should frame yourself – you believe in evolution. However, there are a few parts of the theory that you disagree with. Don’t be obnoxious, but don’t be overly shy either. Just be frank. Do you believe in evolution? “Yes, but I disagree that common ancestry is universal.” Do you believe in evolution? “Yes, but I don’t think that natural selection alone as a mechanism sufficiently explains life’s diversity.” You don’t even have to put the “yes” and the objection in the same sentence. What do you think about evolution? “The study of evolution is fascinating!” How do you think multicellularity evolved? “I think that multicellularity is a fundamental property of certain organisms, and can’t be evolved piecemeal from the presumed single-celled ancestors.” But you do believe in evolution? “Yes, of course.” Do you think multi-cellular organisms evolved? “Certainly!” From what? “Other multi-cellular organisms.”

If someone challenges you on the definition of evolution, simply challenge them back. What definition of evolution are you using? “I’m using the standard population genetics definition of evolution as the change in gene frequencies over time.” That’s not what evolution is. “What is your definition of evolution?” Evolution means natural selection and common ancestry! “Well, that’s a pretty narrow view of evolution in modern biology. So, while I agree with evolution in general, I don’t agree with your specific view of it.” What’s your specific view? “I’m still learning! But I do find it interesting that….[put your favorite evolutionary or non-evolutionary feature of biology here]”

I'm willing to bet that the vast majority will still never admit that evolution, as defined, is a fact because we can directly observe it happening right before our eyes.

David Klinghoffer Will Bust Your Mark VIII Irony Meter

Back in the days of newsgroups (last century) the howlers in talk.origins developed a running joke about irony meters.

Back in the days of newsgroups (last century) the howlers in talk.origins developed a running joke about irony meters.The lastest version (Mark VIII) is pretty sturdy but from time to time the IDiots come up with a real challenge. You might want to turn off your irony meter before reading any further and especially before following the link.

Here's David Klinghoffer's latest posting on the "prestigious" IDiot site, Evolution News & Views [What Is It about Professors and Reading Comprehension?].

How is it that many professors in the humanities and the sciences seem unable to read an opinion they don't like and then accurately relate the argument -- say it back to their interlocutor -- before trying to rebut it? This is a basic skill in communication that comes in handy in many areas of life, including personal relationships

The Problem with Psychology

Ed Yong of Not Exactly Rocket Science has just published a scathing criticism of the entire field of psychology [Replication studies: Bad copy]. The fact that this article appears in Nature should be of great concern to all psychologists. Here's the two opening paragraphs.

One of the most remarkable things about Ed Yong's paper is that he doesn't even mention evolutionary psychology! I think that the absurdity of most evolutionary psychology papers is more than sufficient reason to question whether the entire field is fatally flawed [Boobies and Evolutionary Psychologists].

There's clearly something wrong. Can it be possible that an entire discipline has gone off the rails?1

For many psychologists, the clearest sign that their field was in trouble came, ironically, from a study about premonition. Daryl Bem, a social psychologist at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, showed student volunteers 48 words and then abruptly asked them to write down as many as they could remember. Next came a practice session: students were given a random subset of the test words and were asked to type them out. Bem found that some students were more likely to remember words in the test if they had later practised them. Effect preceded cause.There's lots more where that comes from. Read the entire article.

Bem published his findings in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (JPSP) along with eight other experiments1 providing evidence for what he refers to as “psi”, or psychic effects. There is, needless to say, no shortage of scientists sceptical about his claims. Three research teams independently tried to replicate the effect Bem had reported and, when they could not, they faced serious obstacles to publishing their results. The episode served as a wake-up call. “The realization that some proportion of the findings in the literature simply might not replicate was brought home by the fact that there are more and more of these counterintuitive findings in the literature,” says Eric-Jan Wagenmakers, a mathematical psychologist from the University of Amsterdam.

One of the most remarkable things about Ed Yong's paper is that he doesn't even mention evolutionary psychology! I think that the absurdity of most evolutionary psychology papers is more than sufficient reason to question whether the entire field is fatally flawed [Boobies and Evolutionary Psychologists].

There's clearly something wrong. Can it be possible that an entire discipline has gone off the rails?1

1. Saying that there's a problem with a discipline is not the same as saying that there's a problem with every single psychologist. What I'm saying is that the good psychologists don't seem to have the same influence that good biochemists and good evolutionary biologist (mostly) have on their respective disciplines.

Wednesday, May 16, 2012

Cellphones in the Classroom

Here's an interesting video clip on the advantages (?) of encouraging students to use cellphones in the classroom.

Students have been using laptops in my classes for more than a dozen years. They were never using them for the sole purpose of taking notes, especially since the installation of WiFi. Smart phones don't change anything.

If you teach a class that engages students and gets them to debate and discuss the issues then they won't have time to live tweet or do anything else on their smart phones. If you are teaching difficult and challenging concepts and principles, then you are likely to keep their attention. If you teach a class that allows students to busy themselves with lots of other tasks during the lecture, and still get a good grade, then they will do that.

I pose the following question ... if your students can spend a considerable amount of time using their smart phones during class then they are not giving the class their full attention. Are you teaching effectively?

And whatever happened to note-taking? How can you take notes with a smart phone in your hand? Is taking notes an old fashioned concept that should be abandoned?

Students have been using laptops in my classes for more than a dozen years. They were never using them for the sole purpose of taking notes, especially since the installation of WiFi. Smart phones don't change anything.

If you teach a class that engages students and gets them to debate and discuss the issues then they won't have time to live tweet or do anything else on their smart phones. If you are teaching difficult and challenging concepts and principles, then you are likely to keep their attention. If you teach a class that allows students to busy themselves with lots of other tasks during the lecture, and still get a good grade, then they will do that.

I pose the following question ... if your students can spend a considerable amount of time using their smart phones during class then they are not giving the class their full attention. Are you teaching effectively?

And whatever happened to note-taking? How can you take notes with a smart phone in your hand? Is taking notes an old fashioned concept that should be abandoned?

On Changing Education Because It's What the Students Want

In a previous post I mentioned an article by Sidneyeve Matrix who advocates changing the "traditional" form of undergraduate university education by incorporating more technology [Challenges, Opportunities, and New Expectations]. In that post, I concentrated on one of the arguments for online courses [On the Quality of Online Courses].

In this post I want to bring up one of the arguments for introducing new technology into a course. I'm going to pick a quote from Sidneyeve Matrix's article but she's not the only one who brings it up.

The third statement says that it's "undeniable" that students expect to see some technology in their class. What does this mean? Will they be satisfied if they see a power point presentation and a website? Do they expect their professors to befriend them on facebook or follow their tweets? We don't know. The statement is devoid of meaning.

However, what seems to be "undeniable" is that there are some professors who think that it's important to give students whatever they want. These professors seem to think that it's the students, not them, who are the experts on undergraduate education. Is there any evidence for that?

Of course not. The reason for giving students what they want is clearly spelled out in the last sentence. If you give them what they want then you'll get good student evaluations.

In fairness, she also mentions "engagement." If student engagement is one of your goals—it's one of mine—then that's a reason for exploring technology options. That may, or may not, be associated with student satisfaction. My experience suggests that it's not. I first started an online discussion forum for students in 1987-88 using a usenet forum running on a VAX. Very few students used it but the ones who did liked it a lot.

Over the last 25 years, I've tried various ways of encouraging student engagement on the internet including, in the last iteration, trying to get students to read and comment on blogs. The result is always the same. A subset of the class has a great time "engaging" and a larger subset resists all attempts to draw them in. The most effective way to encourage, and reward, engagement is to do it in class with the students right there with you. The downside is that a good chunk of your class are miserable because they don't want to "engage" in their own learning. They would rather be passive learners.

Option three: (3) make the professor change the course in order to cater to the student's view of how a course should be taught, is not a reasonable option.

Many of these debates and discussions about the use of new technology in the classroom assume that there's resistance from old professors who are uncomfortable with new technology and/or social media. That may be true of some professors but many of my mature colleagues have been computer literate since before many young professors were born. Many of my colleagues have been using email for thirty years. They have had webpages, including course webpages, since the web was created twenty years ago. In spite of the fact that they are not intimidated by technology—what science professor is intimidated by new technology?—they have not radically transformed their way of teaching in the past several decades. Why is that? Is it because they have the wisdom and experience to know that new technology is not the best way to improve undergraduate education?

In this post I want to bring up one of the arguments for introducing new technology into a course. I'm going to pick a quote from Sidneyeve Matrix's article but she's not the only one who brings it up.

There’s a torrent of research demonstrating the costs and benefits of using social, mobile, and digital technology enhancements to teach; yet it’s inconclusive whether these result in higher student outcomes. Of course, there are multiple bottom lines to consider. What’s undeniable is that even though digital divides exist, today’s students expect to see some technology used in their classes. It follows that we can expect increased engagement and higher student satisfaction when profs power-up. In my experience, exceedingly positive end-of-term student surveys and reviews in my ed-tech enhanced courses document a beneficial halo effect.The first statement is true, as far as I know. There are no sound pedagogical reasons for incorporating social media and other technologies into a course. That means there must be other, not-pedagogical, reasons for change.

The third statement says that it's "undeniable" that students expect to see some technology in their class. What does this mean? Will they be satisfied if they see a power point presentation and a website? Do they expect their professors to befriend them on facebook or follow their tweets? We don't know. The statement is devoid of meaning.

However, what seems to be "undeniable" is that there are some professors who think that it's important to give students whatever they want. These professors seem to think that it's the students, not them, who are the experts on undergraduate education. Is there any evidence for that?

Of course not. The reason for giving students what they want is clearly spelled out in the last sentence. If you give them what they want then you'll get good student evaluations.

In fairness, she also mentions "engagement." If student engagement is one of your goals—it's one of mine—then that's a reason for exploring technology options. That may, or may not, be associated with student satisfaction. My experience suggests that it's not. I first started an online discussion forum for students in 1987-88 using a usenet forum running on a VAX. Very few students used it but the ones who did liked it a lot.

Over the last 25 years, I've tried various ways of encouraging student engagement on the internet including, in the last iteration, trying to get students to read and comment on blogs. The result is always the same. A subset of the class has a great time "engaging" and a larger subset resists all attempts to draw them in. The most effective way to encourage, and reward, engagement is to do it in class with the students right there with you. The downside is that a good chunk of your class are miserable because they don't want to "engage" in their own learning. They would rather be passive learners.

In order for professors to engage in podcasting or online lectures or tweeting, or supporting their colleagues who opt to publish in open source journals or participate in online conferences, they must see real benefits and an immediate, significant return on investment. Perhaps for some profs evidence of increased student satisfaction and engagement will win them over.I hope that "increased student satisfaction" will never be a primary motive for change. It may be a secondary benefit but that's not the same thing. Our job is to teach effectively. If the proper teaching methods don't "please" the students then our job is to convince them that they need to change their minds about what gives them pleasure. If they can't do that then they might have only two choices: (1) be miserable throughout their stay in university, or (2) drop out.

Option three: (3) make the professor change the course in order to cater to the student's view of how a course should be taught, is not a reasonable option.

Many of these debates and discussions about the use of new technology in the classroom assume that there's resistance from old professors who are uncomfortable with new technology and/or social media. That may be true of some professors but many of my mature colleagues have been computer literate since before many young professors were born. Many of my colleagues have been using email for thirty years. They have had webpages, including course webpages, since the web was created twenty years ago. In spite of the fact that they are not intimidated by technology—what science professor is intimidated by new technology?—they have not radically transformed their way of teaching in the past several decades. Why is that? Is it because they have the wisdom and experience to know that new technology is not the best way to improve undergraduate education?

Tuesday, May 15, 2012

On the Quality of Online Courses

Are online courses a good thing, a bad thing, or relatively neutral? There's much to debate.

The main issue, as far as I'm concerned, is pedagogical. Are online courses a good way to teach critical thinking—the primary goal of undergraduate education?

There are tangential issues that often get in the way of dealing with the important questions and I'd like to deal with one of them here.

In a previous post [Is Canada Lagging Behind in Online Education?] I criticized a newspaper article by Michael Geist because he made an incorrect assumption. He assumed that any online course from a "top-tier" university would be serious competition for the average Canadian school. I selected two courses from MIT and showed that the quality of their biochemistry teaching was not a threat.

This point needs to be emphasized. Just because an online undergraduate course comes from Harvard, MIT, or Stanford does not mean that it's a good quality course. In my own field of biochemistry I know of many, many teachers in small schools throughout North America who can teach biochemistry better than famous research professors at the so-called "top-tier" schools.

It still may be true that students will flock to the Harvard, MIT, and Stanford courses and pay those schools for biochemistry credits but let's not assume, without justification, that they are getting a better education.

Today I received a copy of Academic Matters: OCUFA's Journal of Higher Education, a magazine published by the Ontario Federation of University Faculty Associations (OCUFA). The articles are devoted to technology in the classroom ("Professor 2.0." ugh!). An article by Sidneyeve Matrix [Challenges, Opportunities, and New Expectations] caught my eye. She says,

University Academy offer an online course in biochemistry that it's necessarily a good course.

The MIT examples I highlighted in my previous post says that this is a a bad assumption. You can look at the Stanford University Courses and make up your own mind.

Here's the important point: don't just assume that because an online course exists, it is necessarily a good course. You may have legitimate reasons for thinking that online courses are good things, but that doesn't excuse you from actually looking at the quality of an online course before declaring that the producers of such a course did a good job. Putting a bad course online is worse than putting no course online no matter what you might think of online courses.

The main issue, as far as I'm concerned, is pedagogical. Are online courses a good way to teach critical thinking—the primary goal of undergraduate education?

There are tangential issues that often get in the way of dealing with the important questions and I'd like to deal with one of them here.

In a previous post [Is Canada Lagging Behind in Online Education?] I criticized a newspaper article by Michael Geist because he made an incorrect assumption. He assumed that any online course from a "top-tier" university would be serious competition for the average Canadian school. I selected two courses from MIT and showed that the quality of their biochemistry teaching was not a threat.

This point needs to be emphasized. Just because an online undergraduate course comes from Harvard, MIT, or Stanford does not mean that it's a good quality course. In my own field of biochemistry I know of many, many teachers in small schools throughout North America who can teach biochemistry better than famous research professors at the so-called "top-tier" schools.

It still may be true that students will flock to the Harvard, MIT, and Stanford courses and pay those schools for biochemistry credits but let's not assume, without justification, that they are getting a better education.

Today I received a copy of Academic Matters: OCUFA's Journal of Higher Education, a magazine published by the Ontario Federation of University Faculty Associations (OCUFA). The articles are devoted to technology in the classroom ("Professor 2.0." ugh!). An article by Sidneyeve Matrix [Challenges, Opportunities, and New Expectations] caught my eye. She says,

When Stanford University offers massively open online courses (MOOCs) in science and engineering, in one case drawing over 150,000 participants, people take notice. When the Khan Academy wins significant Microsoft funding, posts 3,000 instructional videos online, and attracts massive traffic, stories proliferate about the future of self-directed, online, informal e-learning. ... Critics ask, what’s the value of having students attend a lecture in real time if essentially the same material is covered by world-renowned professors on professional-quality video courtesy of free services at TED-Ed or YouTube Education? ... Why pay enormous fees to learn from faculty in an accredited university program, when MITx offers free online courseware with options for students to get peer-to-peer and professor feedback, assessment and earn branded certificates of achievement? What is the return on investment for students (and perhaps their parents) opting to earn their credentials at a bricks-and-mortar university when they could join the 30,000 others enrolled at the London School of Business and Finance in their Global MBA program—delivered online via a Facebook app?There's a myth here that needs exposing. The quality of undergraduate education in the sciences1 should be judged by the content of the course and not the prestige of the university that offers it. Let's not get bamboozled into thinking that just because Stanford and Khan

The MIT examples I highlighted in my previous post says that this is a a bad assumption. You can look at the Stanford University Courses and make up your own mind.

Here's the important point: don't just assume that because an online course exists, it is necessarily a good course. You may have legitimate reasons for thinking that online courses are good things, but that doesn't excuse you from actually looking at the quality of an online course before declaring that the producers of such a course did a good job. Putting a bad course online is worse than putting no course online no matter what you might think of online courses.

1. I restricted myself to the sciences because we are presumably judging quality by the ability to teach critical thinking and factually correct material. There may well be degrees and programs where this isn't important. For example, it may not be important who teaches MBA courses since the goal is just to get a degree to put on your CV. In that case the prestige of the London School of Business and Finance may be far more important than whether you are actually learning something useful, or correct.

Subscribe to:

Comments

(

Atom

)