Mendel's Garden #14 has been posted on Epigenetic News.

Walther Hermann Nernst won the Nobel Prize in 1920 for his work in understanding the energy of reactions. The main work is summarized in the presentation speech,

Walther Hermann Nernst won the Nobel Prize in 1920 for his work in understanding the energy of reactions. The main work is summarized in the presentation speech,Before Nernst began his actual thermochemical work in 1906, the position was as follows. Through the law of the conservation of energy, the first fundamental law of the theory of heat, it was possible on the one hand to calculate the change in the evolution of heat with the temperature. This is due to the fact that this change is equal to the difference between the specific heats of the original and the newly-formed substances, that is to say, the amount of heat required to raise their temperature from 0° to 1° C. According to van't Hoff, one could on the other hand calculate the change in chemical equilibrium, and consequently the relationship with temperature, if one knew the point of equilibrium at one given temperature as well as the heat of reaction.Today, Nernst is known for his other contributions to thermodynamics. In biochemistry he is responsible for the Nernst equation that relates standard reduction potentials and Gibbs free energy.

The big problem, however, that of calculating the chemical affinity or the chemical equilibrium from thermochemical data, was still unsolved.

With the aid of his co-workers Nernst was able through extremely valuable experimental research to obtain a most remarkable result concerning the change in specific heats at low temperatures.

That is to say, it was shown that at relatively low temperatures specific heats begin to drop rapidly, and if extreme experimental measures such as freezing with liquid hydrogen are used to achieve temperatures approaching absolute zero, i.e. in the region of -273° C, they fall almost to zero.

This means that at these low temperatures the difference between the specific heats of various substances comes even closer to zero, and thus that the heat of reaction for solid and liquid substances practically becomes independent of temperature at very low temperatures.

where n is the number of electrons transferred and ℱ (F) is Faraday’s constant (96.48 kJ V-1 mol-1). ΔE°ʹ is defined as the difference in volts between the standard reduction potential of the electron-acceptor system and that of the electron-donor system. The Δ (delta) symbol indicates a change or a difference between two values.

where n is the number of electrons transferred and ℱ (F) is Faraday’s constant (96.48 kJ V-1 mol-1). ΔE°ʹ is defined as the difference in volts between the standard reduction potential of the electron-acceptor system and that of the electron-donor system. The Δ (delta) symbol indicates a change or a difference between two values. You may recall that electrons tend to flow from half-reactions with a more negative standard reduction potential to those with a more positive one. For example, in the pyruvate dehydrogenase reaction electrons flow from pyruvate (E°' = -0.48 V) to NAD+ (E°' = -0.32 V). We can calculate the change in standard reduction potentials; it's equal to +0.16 V [-0.32 - (-0.48) = +0.16].

You may recall that electrons tend to flow from half-reactions with a more negative standard reduction potential to those with a more positive one. For example, in the pyruvate dehydrogenase reaction electrons flow from pyruvate (E°' = -0.48 V) to NAD+ (E°' = -0.32 V). We can calculate the change in standard reduction potentials; it's equal to +0.16 V [-0.32 - (-0.48) = +0.16].  Just as the actual Gibbs free energy change for a reaction is related to the standard Gibbs free energy change by this equation, an observed difference in reduction potentials (ΔE) is related to the difference in the standard reduction potentials (ΔE°') by the Nernst equation.

Just as the actual Gibbs free energy change for a reaction is related to the standard Gibbs free energy change by this equation, an observed difference in reduction potentials (ΔE) is related to the difference in the standard reduction potentials (ΔE°') by the Nernst equation.  For a reaction involving the oxidation and reduction of two molecules, A and B,

For a reaction involving the oxidation and reduction of two molecules, A and B, the Nernst equation is

the Nernst equation is where [Aox] is the concentration of oxidized A inside the cell. The Nernst equation tells us the actual difference in reduction potential (ΔE) and not the artificial standard change in reduction potential (ΔE°ʹ).

where [Aox] is the concentration of oxidized A inside the cell. The Nernst equation tells us the actual difference in reduction potential (ΔE) and not the artificial standard change in reduction potential (ΔE°ʹ). where Q represents the ratio of the actual concentrations of reduced and oxidized species. To calculate the electromotive force of a reaction under nonstandard conditions, use the Nernst equation and substitute the actual concentrations of reactants and products. Keep in mind that a positive E value indicates that an oxidation-reduction reaction will have a negative value for the standard Gibbs free energy change.

where Q represents the ratio of the actual concentrations of reduced and oxidized species. To calculate the electromotive force of a reaction under nonstandard conditions, use the Nernst equation and substitute the actual concentrations of reactants and products. Keep in mind that a positive E value indicates that an oxidation-reduction reaction will have a negative value for the standard Gibbs free energy change. and

and Since the NAD+ half-reaction has the more negative standard reduction potential, NADH is the electron donor and oxygen is the electron acceptor. The net reaction is

Since the NAD+ half-reaction has the more negative standard reduction potential, NADH is the electron donor and oxygen is the electron acceptor. The net reaction is and the change in standard reduction potential is

and the change in standard reduction potential is Using the equations described above we get

Using the equations described above we get What this tells us is that a great deal of energy can be released when electrons are passed from NADH to oxygen provided the conditions inside the cell resemble those for the standard reduction potentials (they do). The standard Gibbs free energy change for the formation of ATP from ADP + Pi is -32 kJ mol-1 (the actual free-energy change is greater under the conditions of the living cell, it's about -45 kJ mol-1). This strongly suggests that the energy released during the oxidation of NADH under cellular conditions is sufficient to drive the formation of several molecules of ATP. Actual measurements reveal that the oxidation of NADH can be connected to formation of 2.5 molecules of ATP giving us confidence that the theory behind oxidation-reduction reactions is sound.

What this tells us is that a great deal of energy can be released when electrons are passed from NADH to oxygen provided the conditions inside the cell resemble those for the standard reduction potentials (they do). The standard Gibbs free energy change for the formation of ATP from ADP + Pi is -32 kJ mol-1 (the actual free-energy change is greater under the conditions of the living cell, it's about -45 kJ mol-1). This strongly suggests that the energy released during the oxidation of NADH under cellular conditions is sufficient to drive the formation of several molecules of ATP. Actual measurements reveal that the oxidation of NADH can be connected to formation of 2.5 molecules of ATP giving us confidence that the theory behind oxidation-reduction reactions is sound.Then there's the problem on the other side -- among the atheists such as Richard Dawkins who have been labelled "fanatics." Now, it is absolutely true that Dawkins' tone is often as charming as fingernails dragged slowly down a chalkboard. But just what is the core of Dawkins' radical message?[Hat Tip: PZ Myers]

Well, it goes something like this: If you claim that something is true, I will examine the evidence which supports your claim; if you have no evidence, I will not accept that what you say is true and I will think you a foolish and gullible person for believing it so.

That's it. That's the whole, crazy, fanatical package.

When the Pope says that a few words and some hand-waving causes a cracker to transform into the flesh of a 2,000-year-old man, Dawkins and his fellow travellers say, well, prove it. It should be simple. Swab the Host and do a DNA analysis. If you don't, we will give your claim no more respect than we give to those who say they see the future in crystal balls or bend spoons with their minds or become werewolves at each full moon.

And for this, it is Dawkins, not the Pope, who is labelled the unreasonable fanatic on par with faith-saturated madmen who sacrifice children to an invisible spirit.

This is completely contrary to how we live the rest of our lives. We demand proof of even trivial claims ("John was the main creative force behind Sergeant Pepper") and we dismiss those who make such claims without proof. We are still more demanding when claims are made on matters that are at least temporarily important ("Saddam Hussein has weapons of mass destruction" being a notorious example).

So isn't it odd that when claims are made about matters as important as the nature of existence and our place in it we suddenly drop all expectation of proof and we respect those who make and believe claims without the slightest evidence? Why is it perfectly reasonable to roll my eyes when someone makes the bald assertion that Ringo was the greatest Beatle but it is "fundamentalist" and "fanatical" to say that, absent evidence, it is absurd to believe Muhammad was not lying or hallucinating when he claimed to have long chats with God?

None of the reactions of glycolysis result in the direct reduction of molecular oxygen. In all cases, the release of electrons when glucose is broken down to CO2 is coupled to temporary electron storage in various coenzymes. We have already encountered several of these electron storage molecules such as ubiquinone, FMN & FAD, and NADPH.

None of the reactions of glycolysis result in the direct reduction of molecular oxygen. In all cases, the release of electrons when glucose is broken down to CO2 is coupled to temporary electron storage in various coenzymes. We have already encountered several of these electron storage molecules such as ubiquinone, FMN & FAD, and NADPH. How do we know which direction electron are going to flow? For example, if ubiquinone is reduced to ubiquinol by acquiring two electrons then where do the electrons come from? Can NADH pass electrons to ubiquinone or does ubiquinol pass its two electrons to NAD+? And where does FAD+ fit? Can it receive electrons from NADH?

How do we know which direction electron are going to flow? For example, if ubiquinone is reduced to ubiquinol by acquiring two electrons then where do the electrons come from? Can NADH pass electrons to ubiquinone or does ubiquinol pass its two electrons to NAD+? And where does FAD+ fit? Can it receive electrons from NADH? The direction of the current through the circuit in the figure indicates that Zn is more easily oxidized than Cu (i.e., Zn is a stronger reducing agent than Cu). The reading on the voltmeter represents a potential difference—the difference between the reduction potential of the reaction on the left and that on the right. The measured potential difference is the electromotive force.

The direction of the current through the circuit in the figure indicates that Zn is more easily oxidized than Cu (i.e., Zn is a stronger reducing agent than Cu). The reading on the voltmeter represents a potential difference—the difference between the reduction potential of the reaction on the left and that on the right. The measured potential difference is the electromotive force. The table below gives the standard reduction potentials at pH 7.0 (E̊́) of some important biological half-reactions. Electrons flow spontaneously from the more readily oxidized substance (the one with the more negative reduction potential) to the more readily reduced substance (the one with the more positive reduction potential). Therefore, more negative potentials are assigned to reaction systems that have a greater tendency to donate electrons (i.e., systems that tend to oxidize most easily).

The table below gives the standard reduction potentials at pH 7.0 (E̊́) of some important biological half-reactions. Electrons flow spontaneously from the more readily oxidized substance (the one with the more negative reduction potential) to the more readily reduced substance (the one with the more positive reduction potential). Therefore, more negative potentials are assigned to reaction systems that have a greater tendency to donate electrons (i.e., systems that tend to oxidize most easily).

It's important to note the direction of all these reactions is written in the form of a reduction or gain of electrons. That's not important when it comes to determining the direction of electron flow. For example, note that the reduction of acetyl-CoA to pyruvate is at the top of the list (E̊́= -0.48 V). This is the reaction catalyzed by pyruvate dehydrogenase. Electrons released by the oxidation of pyruvate will flow to any half reaction that has a higher (less negative) standard reduction potential. In this case the electrons end up in NADH (E̊́ = -0.32 V).

It's important to note the direction of all these reactions is written in the form of a reduction or gain of electrons. That's not important when it comes to determining the direction of electron flow. For example, note that the reduction of acetyl-CoA to pyruvate is at the top of the list (E̊́= -0.48 V). This is the reaction catalyzed by pyruvate dehydrogenase. Electrons released by the oxidation of pyruvate will flow to any half reaction that has a higher (less negative) standard reduction potential. In this case the electrons end up in NADH (E̊́ = -0.32 V). When two atoms of hydrogen combine to form H2 both atoms succeed in filling their outer shells with two electron by sharing electrons. The shared pair of electrons is the covalent bond. The type of structures shown in the equation are called Lewis Structures. The dots represent electrons in the outer shell of the atom.

When two atoms of hydrogen combine to form H2 both atoms succeed in filling their outer shells with two electron by sharing electrons. The shared pair of electrons is the covalent bond. The type of structures shown in the equation are called Lewis Structures. The dots represent electrons in the outer shell of the atom. In this example, oxygen with six electrons in the valence shell is combining with two hydrogen atoms to form water (H2O). By sharing electrons both the hydrogen atoms and the oxygen atom will complete their outer shells of electrons—hydrogen with two electrons and oxygen with eight.

In this example, oxygen with six electrons in the valence shell is combining with two hydrogen atoms to form water (H2O). By sharing electrons both the hydrogen atoms and the oxygen atom will complete their outer shells of electrons—hydrogen with two electrons and oxygen with eight.

Carbon has an atomic number of 6, which means that it has two electrons in the inner shell and only four electrons in the outer shell. Carbon can combine with four other atoms to fill up its outer shell with eight electrons. This ability to combine with several different atoms is one of the reasons why carbon is such a versatile atom. The structure of ethanol (CH3CH2OH, left) illustrates this versatility. Note that each atom has a complete outer shell of electrons and that each carbon atom is covalently bonded to four other atoms.

Carbon has an atomic number of 6, which means that it has two electrons in the inner shell and only four electrons in the outer shell. Carbon can combine with four other atoms to fill up its outer shell with eight electrons. This ability to combine with several different atoms is one of the reasons why carbon is such a versatile atom. The structure of ethanol (CH3CH2OH, left) illustrates this versatility. Note that each atom has a complete outer shell of electrons and that each carbon atom is covalently bonded to four other atoms. The outline of the enzyme is shown in blue. One of the key concepts in biochemistry is that enzymes speed up reactions, in part, by supplying and storing electrons. In this case an electron withdrawing group (X) pulls electrons from oxygen and this weakens the carbon-oxygen double bond (keto group). Carbon #2, in turn, pulls an electron from carbon #3 weakening the C3-C4 bond that will be broken. (Aldolase cleaves a six-carbon compound into two three-carbon compounds as shown here. It also preforms the reverse reaction where two three-carbon compounds are combined to form a six-carbon compound.)

The outline of the enzyme is shown in blue. One of the key concepts in biochemistry is that enzymes speed up reactions, in part, by supplying and storing electrons. In this case an electron withdrawing group (X) pulls electrons from oxygen and this weakens the carbon-oxygen double bond (keto group). Carbon #2, in turn, pulls an electron from carbon #3 weakening the C3-C4 bond that will be broken. (Aldolase cleaves a six-carbon compound into two three-carbon compounds as shown here. It also preforms the reverse reaction where two three-carbon compounds are combined to form a six-carbon compound.) According to the US Defense Department, Canada is planting coins containing secret radio transmitters on US Defense contractors travelling in Canada ['Poppy quarter' behind spy coin alert]. The coins are the 2004 commemorative quarters issued to remember those who died in Canada's wars. The coins have a red poppy in the center [In Flanders Fields].

According to the US Defense Department, Canada is planting coins containing secret radio transmitters on US Defense contractors travelling in Canada ['Poppy quarter' behind spy coin alert]. The coins are the 2004 commemorative quarters issued to remember those who died in Canada's wars. The coins have a red poppy in the center [In Flanders Fields].WASHINGTON - An odd-looking Canadian quarter with a bright red flower was the culprit behind a false espionage warning from the Defense Department about mysterious coins with radio frequency transmitters, The Associated Press has learned.I can see why the contractors were confused. American coins and paper money are so boring they probably thought every country had boring money.

ADVERTISEMENT

The harmless "poppy quarter" was so unfamiliar to suspicious U.S. Army contractors traveling in Canada that they filed confidential espionage accounts about them. The worried contractors described the coins as "filled with something man-made that looked like nano-technology," according to once-classified U.S. government reports and e-mails obtained by the AP.

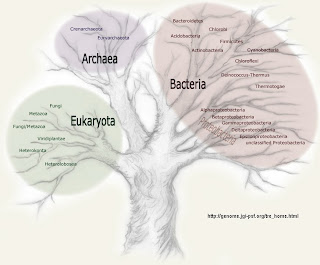

This is a series of postings that describe the Three Domain Hypothesis. The Three Domain Hypothesis is the idea that life is divided into three domains—bacteria, archaebacteria, and eukaryotes—and that the archaebacteria and eukaryotes share a common ancestor. An example of this tree of life is shown on the Dept. of Energy (USA) Joint Genome Initiative website [JGI Microbial Genomes] (left).

This is a series of postings that describe the Three Domain Hypothesis. The Three Domain Hypothesis is the idea that life is divided into three domains—bacteria, archaebacteria, and eukaryotes—and that the archaebacteria and eukaryotes share a common ancestor. An example of this tree of life is shown on the Dept. of Energy (USA) Joint Genome Initiative website [JGI Microbial Genomes] (left).

Name this molecule. We need the exact name since it's pretty easy to guess one of the trivial names.

Name this molecule. We need the exact name since it's pretty easy to guess one of the trivial names. Mike Lake is the Canadian member of parliament for Edmonton-Mill Woods-Beaumont. He belongs to the Conservative Party of Stephen Harper.

Mike Lake is the Canadian member of parliament for Edmonton-Mill Woods-Beaumont. He belongs to the Conservative Party of Stephen Harper. Pharmacologists at the recent Experimental Biology meeting in Washington were excited about their Abel numbers [Six degrees of pharmacology]. The Abel number represents the number of links to John J. Abel, the founder of modern pharmacology. In this case the links have to be through authors on a publication.

Pharmacologists at the recent Experimental Biology meeting in Washington were excited about their Abel numbers [Six degrees of pharmacology]. The Abel number represents the number of links to John J. Abel, the founder of modern pharmacology. In this case the links have to be through authors on a publication. Friday's Urban Legend: FALSE

Friday's Urban Legend: FALSEAre you a Non- Smoker or Against smoking all together ?Another version has "them" putting MSG in the coffee instead of nicotine. That's the version that I received this week from well-meaning, but not very skeptical, friends.

Do you ever wonder why you have to have your coffee every morning?

** TIM HORTON'S SHOCKER **

A man from Arkansas came up to Canada for a visit only to find himself in the hospital after a couple of days. Doctor's told him that he had suffered of cardiac arrest. He was allergic to Nicotine. The man did not understand why that would of happened as he does not smoke knowing full well he was allergic to Nicotine. He told the doctor that he had not done anything different while he was on vacation other than having Tim Horton's coffee. The man then went back to Tim Horton's and asked what was in their coffee. Tim Horton's refuses to divulge that information. After threatening legal action, Tim Horton's finally admitted.....

*** THERE IS NICOTINE IN TIM HORTON'S COFFEE ***

A girl I know was on the patch to quit smoking. After a couple of days she was having chest pains & was rushed to the hospital. The doctor told her that she was on a Nicotine overload. She swore up & down that she had not been smoking. SHE WAS HAVING HER COFFEE EVERY MORNING.

Now imagine a women who quits smoking because she finds out that she is pregnant, but still likes to have her Tim Horton's once in a while.

THIS IS NOT A JOKE, PLEASE PASS THIS ALONG.... YOU MIGHT SEE THIS ON THE NEWS SOON.

You scored as Modernist. Modernism represents the thought that science and reason are all we need to carry on. Religion is unnecessary and any sort of spirituality halts progress. You believe everything has a rational explanation. 50% of Americans share your world-view.

What is Your World View? created with QuizFarm.com |

According to Woolhandler, by looking at already ill patients, the researchers eliminated any Canadian lifestyle advantage and just examined the degree to which the two systems affected patient deaths. (Mortality was the one kind of data they could extract from a disparate pool of 38 papers examining everything from kidney failure to rheumatoid arthritis.)These studies are never conclusive. There will always be people who quibble about this or that and just as you might expect there is the obligatory complaint about wait times in Canada.

Overall, the results favored Canadians, who were 5 percent less likely than Americans to die in the course of treatment. Some disorders, such as kidney failure, favored Canadians more strongly than Americans, whereas others, such as hip fracture, had slightly better outcomes in the U.S. than in Canada. Of the 38 studies the authors surveyed, which were winnowed down from a pool of thousands, 14 favored Canada, five the U.S., and 19 yielded mixed results.

The study's authors highlight the fact that per capita spending on health care is 89 percent higher in the U.S. than in Canada. "One thing that people generally know is that the administration costs are much higher in the U.S.," Groome notes. Indeed, one study by Woolhandler published in The New England Journal of Medicine in 2003 found that 31 percent of spending on health care in the U.S. went to administrative costs, whereas Canada spent only 17 percent on the same functions.I suspect there are many European countries with health care systems that are just as good as the one in America. I suspect that Japan, New Zealand, and Australia have good health care as well. I've never seen any data that shows that the quality of health care in America is better than everywhere else in the world. It seems to be one of those myths of American superiority that has no basis in fact. The myth prevents Americans from joining the rest of the civilized world and adopting socialized medicine.