Emily Mortola and Manyuan Long have just published an article in American Scientist about Turning Junk into Us: How Genes Are Born. The article contains a lot of misinformaton about junk DNA that I'll discuss below.

Emily Mortola is a freelance science writer who worked with Manyuan Long when she was an undergraduate (I think). Manyuan Long is the Edna K. Papazian Distinguished Service Professor of Ecology and Evolution in the Department of Ecology and Evolution at the University of Chicago. His main research interest is the origin of new genes. It's reasonable to suspect that he's an expert on genome structure and evolution.

The article is behind a paywall so most of you can't see anything more than the opening paragraphs so let's look at those first. The second sentence is ...

As we discovered in 2003 with the conclusion of the Human Genome Project, a monumental 13-year-long research effort to sequence the entire human genome, approximately 98.8 percent of our DNA was categorized as junk.

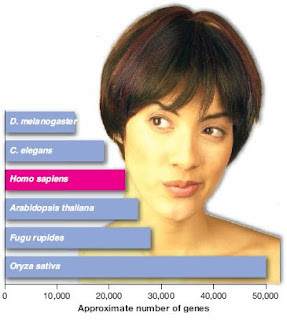

This is not correct. The paper on the finished version of the human genome sequence was published in October 2004 (Finishing the euchromatic sequence of the human genome) and the authors reported that the coding exons of protein-coding genes covered about 1.2% of the genome. However, the authors also noted that there are many genes for tRNAs, ribosomal RNAs, snoRNAs, microRNAs, and probably other functional RNAs. Although they don't mention it, the authors must also have been aware of regulatory sequences, centromeres, telomeres, origins of replication and possibly other functional elements. They never said that all noncoding DNA (98.8%) was junk because that would be ridiculous. It's even more ridiculous to say it in 2021 [Stop Using the Term "Noncoding DNA:" It Doesn't Mean What You Think It Means].

The part of the article that you can see also lists a few "Quick Takes" and one of them is ...

Close to 99 percent of our genome has been historically classified as noncoding, useless “junk” DNA. Consequently, these sequences were rarely studied.

This is also incorrect as many scientists have pointed out repeatedly over the past fifty years or so. At no time in the past 50 years has any knowledgeable scientist ever claimed that all noncoding DNA is junk. I'm sorely tempted to accuse the authors of this article of lying because they really should know better, especially if they're writing an article about junk DNA in 2021. However, I reluctantly defer to Hanlon's razor.

Mortola and Long claim that mammalian genomes have between 85% to 99% junk DNA and wonder if it could have a function.

To most geneticists, the answer was that it has no function at all. The flow of genetic information—the central dogma of molecular biology—seems to leave no role for all of our intergenic sequences. In the classical view, a gene consists of a sequence of nucleotides of four possible types--adenine, cytosine, guanine, and thymine--represented by the letters A, C, G, and T. Three nucleotides in a row make up a codon, with each codon corresponding to a specific amino acid, or protein subunit, in the final protein product. In active genes, harmful mutations are weeded out by selection and beneficial ones are allowed to persist. But noncoding regions are not expressed in the form of a protein, so mutations in noncoding regions can be neither harmful nor beneficial. In other words, "junk" mutations cannot be steered by natural selection.

Those of you who have read this far will cringe when reading that. There are so many obvious errors in that paragraph that applying Hanlon's razor seems very complimentary. Imagine saying in the 21st centurey that the Central Dogma leaves no role at all for regulatory sequences or ribosomal RNA genes! But there's more; the authors double-down on their incorrect understanding of "gene" in order to fit their misunderstanding of the Central Dogma.

What Is a Gene, Really?

In our de novo gene studies in rice, to truly assess the potential significance of de novo genes, we relied on a strict definition of the word "gene" with which nearly every expert can agree. First, in order for a nucleotide sequence to be considered a true gene, an open reading frame (ORF) must be present. The ORF can be thought of as the "gene itself"; it begins with a starting mark common for every gene and ends with one of three possible finish line signals. One of the key enzymes in this process, the RNA polymerase, zips along the strand of DNA like a train on a monorail, transcribing it into its messenger RNA form. This point brings us to our second important criterion: A true gene is one that is both transcribed and translated. That is, a true gene is first used as a template to make transient messenger RNA, which is then translated into a protein.

Five Things You Should Know if You Want to Participate in the Junk DNA DebateThe authors admit in the next paragraph that some pseudogenes may produce functional RNAs that are never translated into proteins but they don't mention any other types of gene. I can understand why you might concentrate on protein-coding genes if you are studying de novo genes but why not just say that there are two types of genes and either one can arise de novo? But there's another problem with their definition: they left out a key property of a gene. It's not sufficient that a given stretch of DNA is transcribed and the RNA is translated to make a protein: the protein has to have a function before you can say that the stretch of DNA is a gene [What Is a Gene?]. We'll see in a minute why this is important.

The main point of the paper is the birth of de novo genes and the authors discuss their work with the rice genome. They say they've discovered 175 de novo genes but they don't say how many have a real biological function. This is an important problem in this field and it would have been fascinating to see a description of how they go about assigning a function to their, mostly small, pepides [The evolution of de novo genes]. I'm guessing that they just assume a function as soon as they recognize an open reading frame in a transcript.

As you can see from the title of the article, the emphasis is on the idea that de novo genes can arise from junk DNA—a concept that's not seriously disputed. The one good thing about the article is that the authors do not directly state that the reason for junk DNA is to give rise to new genes but this caption is troubling.

The Human Genome Project was a 13-year-long research effort aimed at mapping the entire human genetic sequence. One of its most intriguing findings was the observation that the number of protein-coding genes estimated to exist in humans--approximately 22,300--represents a mere 1.2 percent of our whole genome, with the other 98.8 percent being categorized as noncoding, useless junk. Analyses of this presumed junk DNA in diverse species are now revealing its role in the creation of genes.

Why do science writers continue to spread misinformation about junk DNA when there's so much correct information out there? All you have to do is look [More misconceptions about junk DNA - what are we doing wrong?].