Science writers have always had articles published in the leading science journals such as Science and Nature but over the past few decades their role seems to have increased so that now even lesser journals employ them to write articles, commentary, and press releases. I recently posted an example of where this can go horribly wrong [Society for Molecular Biology and Evolution (SMBE) spreads misinformation about junk DNA].

The role of science writers has come to dominate the pages of Science and Nature so that we now have a situation where only two thirds of the pages in a typical issue are devoted to actual science publications and most readers are concentrating on the news and opinons in the front part of the journal. In some cases, the science writers control the image of these journals as happened at Nature during the ENCODE publicity campaign in 2012. Over at Science, Elisabeth Pennisi has done more to spread misinformation than any scientist in the field of molecular biology.

These are cases where science writers have sacrificed sustance for style. They write nice readable articles that promote the image of their journal but are scientifcally incorrect.

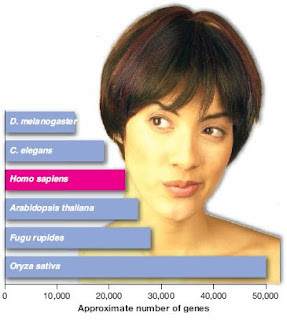

Let's look at a specific example. Back in 2005 Science celebrated its 125th anniversary by publishing "125 Questions: What We Don't Know." One of those questions was "Why Do Humans Have So Few Genes?"—a question that scientists had adequately answered in 2005 but you wouldn't know that from the short article written by Elizabeth Pennisi [SCIENCE Questions: Why Do Humans Have So Few Genes?]. The article was full of untruths and misinformation. There were lots of other questions in that issue that were just as ridiculous if you knew the topics.

Now, you might imagine that these questions were posed by the leading researchers in their fields but you would be wrong. The list of questions was drawn up by editors and science writers as described in the anniversary issue [SCIENCE Questions: Asking the Right Question].

We began by asking Science’s Senior Editorial Board, our Board of Reviewing Editors, and our own editors and writers to suggest questions that point to critical knowledge gaps. The ground rules: Scientists should have a good shot at answering the questions over the next 25 years, or they should at least know how to go about answering them. We intended simply to choose 25 of these suggestions and turn them into a survey of the big questions facing science. But when a group of editors and writers sat down to select those big questions, we quickly realized that 25 simply wouldn’t convey the grand sweep of cutting-edge research that lies behind the responses we received. So we have ended up with 125 questions, a fitting number for Science’s 125th anniversary.

Isn't it remrkable that editors and writers are being asked to evaluate science (substance) as if their opinions were more important than those of the scientists?

Has Science learned from these mistakes? No, because a few months ago they published a new list of 125 questions in collaboration with the 125th anniversary of Shanghai Jiao Tong University: 125 Questions: Exploration and Discovery. The list of questions hasn't gotten any better; it includes questions like, "How do organisms evolve?"; "What genes make us uniquely human?"; and "How are biomolecules organized in cells to function orderly and effectively?" Many of you can imagine what the short accompanying explanation looks like and you would be right.

Pennisi's original question has disappeared but there's a very similar question in the 2021 list.

Why are some genomes so big and others very small?

Genome size, which is the amount of DNA in a cell nucleus, is extremely diverse across animals and plants, and varies more than 64,000-fold. The smallest genome recorded exists in the microsporidian Encephalitozoon intestinalis (a parasite in certain mammals), and the largest genome belongs to a flowering plant known as Paris japonica, which has 150 billion base pairs of DNA per cell (50 times larger than that of a human). Plants are interesting in that their genome size plays an important role in their biology and evolution. But as the authors of a 2017 paper in Trends in Plant Sciences wrote: “Although we now know the major contributors to genome size diversity are non-protein coding, often highly repetitive DNA sequences, why their amounts vary so much still remains enigmatic.”

Sandwalk readers know that knowledgeable scientists came up with good answers to that question about 50 years ago. One answer is that different species have different amounts of junk DNA because some species don't have large enough populations to eliminate it by natural selection. In other cases, the differences are due to polyploidization.

You would think that after all the criticism of Science over their past coverage of genomes and junk DNA that the writers and editors would know this. But they don't, and that's because science writers and editors seem to be remarkably immune to scientific criticism. (The topic probably doesn't come up when they get together at their science writers' conventions.) I'm making the case that they are so focused on style (science writing) that they just don't care about substance (scientific accuracy).

The major journals have a serious problem that they don't recognize. A lot of the stuff that appears in their journals is not scientifically accurate or, at the very least, is misleading. They're not going to fix this problem if their editorial staff is dominated by science journalists.