Casey Luskin has posted an email message that he recently sent to someone who inquired about Intelligent Design Creationism. It describes his view of the debate between Intelligent Design Creationists and scientists [Personal Attacks Against ID Proponents Say More About the Attackers than the Abused].

With that, please let me give you a little introduction to how this debate works. Evolutionists regularly accuse their critics of being "dishonest" and "deceiving." It's a primary tactic they use to respond to criticism and intimidate critics into silence. You're not allowed to dissent from their view and be (a) informed, and (b) honest. Many of them can't fathom the possibility that a person on the other side of the debate could be both.

Here's a fact you might ponder: Virtually every single major person who has criticized the Darwinian viewpoint has faced personal attacks on his or her character. It happens to everyone, myself included. So one of two things are true: Either (1) virtually every single critic of Darwinism (of which there are many) is "dishonest" and "deceiving," or (2) evolutionists habitually respond to scientific challenges with personal attacks.

There's more than two choices here. Let's list the possibilities. Most creationist critics of evolution are ....

- Uninformed and honest

- Uniformed and dishonest

- Informed and honest

- Informed and dishonest

There are creationist critics of evolution who fit into all categories but category #3 is the least populated. I think Michael Denton and Michael Behe qualify. They seem to have a pretty good knowledge of evolutionary biology and they seem to be sincere in their criticism

Category #4 is tricky. There are some creationist critics of evolution who should be informed but they still say some very silly things. This leads me to suspect that they are being dishonest. Jonathan Wells is a good example.

Categories #1 and #2 contain the vast majority of creationist critics of evolution. They really don't know what they're talking about but it doesn't prevent them from talking. I think most of them are honest IDiots—Casey Luskin is an example and so is Phillip Johnson. Some of them are uniformed and dishonest, that's where I would place Bill Dembski and David Berlinski.

Casey Luskin is wrong when he claims that we accuse all creationist critics of evolution of being dishonest and deceitful. Mostly we just accuse them of being uninformed but acting as if they were.1 That's probably due to stupidity and not malevolence.

I've left out a huge number of creationists, including the theistic evolutionists who fall mostly into category #3: informed, honest, but wrong.

Where do the rest of them fit in?

1. Being uninformed is perfectly okay. Most of us are uniformed about a lot of things. You aren't stupid or an idiot just because you don't know something. You become an IDiot when you don't recognize how little you know about a subject but still feel qualified to tell the experts that they are wrong.

A few months ago I posted an exam question from my course on evolution [Exam Question #1]. It was designed to test student's understanding of phylogenetic trees—a serious problem in evolutionary biology. That post generated quite a few comments.

Take a look at this figure from a 2008 issue of Nature. Do you see the problems?

If not, read David Morrison's guest post on Scientipoia: Ambiguity on Phylogenies. He patiently explains all the common misconceptions about phylogenetic trees and references all the important articles in the scientific and pedagogical literature. Once you read his article you will never look at trees the same way again.

You will also be astonished at how bad the scientific literature has become when it comes to explaining phylogenies based on these trees. You would think that evolutionary biologists would have long ago stopped thinking about directions in evolution but it's surprising how often the great chain of being creeps into modern scientific papers.

[Hat Tip: Mike the Mad Biologist]

If you've been watching the Olympics, you've heard the story many times from coaches, athletes, and even team doctors. They all tell you that the performance of endurance athletes is limited by the buildup of lactic acid in their muscles and this is what causes the pain and limits their ability to win a gold medal.

It's the acid that does it and that acid is caused by synthesis of lactic acid taking place during anaerobic exercise, or so the story goes. That happens under extreme conditions when the energy needed by working muscles exceeds the ability to produce it by normal aerobic oxidation. It all sounds so logical ... and so biochemical.

It's all a myth. Lactic acid has nothing to do with acidosis (the buildup of acid in the muscles). In fact, it's not even clear that acidosis is the problem, but let's deal with that another time.

Assuming that acid buildup in muscles is what causes the pain of the long distance runner, where does that acid comes from? In order to answer that question we need a brief lesson on acids.

The word "stasis" entered our consciousness when Gould and Eldredge promoted the concept of punctuated equilibria (see Darwin on Gradualism ). Their observations of the fossil record showed that the morphology of many species remains unchanged for millions of years. Change occurs during speciation by cladogenesis when the new daughter species fixes morphological change, thereby allowing us to recognize it as a different species.

Stasis is an important observation. Here's how Gould describes it in The Structure of Evolutionary Theory (p. 759).

Abrupt appearance may record an absence of information but stasis is data. Eldredge and I became so frustrated by the failure of may colleagues to grasp this evident point—though a quarter century of subsequent debate has finally propelled our claim to general acceptance (while much about punctuated equilibrium remains controversial)—that we ureged the incorporation of this little phrase as a mantra or motto. Say it ten times before breakfast every day for a week, and the argument will surely seep in by osmosis: "stasis is data; stasis is data ..."

Okay, we get it.

What causes stasis? There are many possible explanations. One of the most common is stabilizing selection or the idea that a species is so well-adapted to its environment that any change will be detrimental. According to this view, evolution only occurs when the environment changes.

It's often quite difficult to imagine how a new enzyme activity could have evolved "from scratch." After all, aren't enzymes highly complex proteins with very specific folds? What's the probability of stringing together just the right amino acids by chance in order to get a new enzyme?

In many cases, new enzymes evolve from primitive enzymes that catalyzed similar reactions [see The Evolution of Enzymes from Promiscuous Precursors]. It's quite easy to see how this could happen by gene duplication and there are tons of examples.

But what about the first primitive enzymes themselves? Presumably, they evolved all on their own. When scientists think of this problem, they usually think in terms of evolving a specific modern enzyme. This looks like a long shot, similar to the probability that a specific person will win the lottery tomorrow. What they don't realize is that this is an unnecessarily restrictive scenario.

We're getting close to the beginning of the semester in the northern hemisphere. That means a lot of high school students will be experiencing university for the first time.

In many cases, students will have graduated from high school with only a rudimentary knowledge of some important topics. This isn't necessarily a bad thing as long as they realize that they still have lots to learn. It becomes a bad thing when they think they know the subject but what they know is wrong.

Universities are places that challenge your beliefs and force you to think. New students should embrace this challenge and look forward to giving up misconceptions and ideas that can't stand up to critical analysis. The last thing you want to do as a new student is to begin university with the idea that your high school ideas are always right.

Which brings us to creationism. A large number of students enter university with little or no knowledge of evolution but they are convinced that it's wrong. They will soon encounter teachers who try to convince them that evolution is true. How should students react to this challenge?

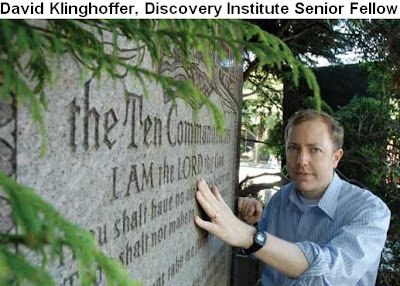

David Klinghoffer1 proposes one solution on the Intelligent Design Creationist blog Evolution News & Views. Here's his advice [A Piece of Unsolicited Advice to Students].

The practical question is nearly self-answering. You should be very, very circumspect about even hinting at your views to people who will end up giving you grades. But beyond that fairly obvious and uninteresting advice, I wanted to add that you should, in your own mind, strive to give respect to your Darwinist teachers no matter how firmly convinced you are that they are wrong.

If I were a professor and had a student who walked into my class intending to inform me that my fundamental views on the subject of my professional training were in error, I can well imagine thinking the kid deserved a good smack. Unfair? Yes, but true. Overturning scientific theories is not the job of an undergraduate student. A student's job is to learn what his teacher has to teach him, so that perhaps later when the student is intellectually ripened, he can lead or participate in a revolution. It's not at all that you need a PhD to hold a dissenting view, but age, thought and experience count for a lot.

At an emotional and personal level, I can sympathize with the Darwinist prof who resents his openly Darwin-doubting student. What arrogance, it must seem, to imagine that what I spent decades mastering, you a little pipsqueak think you're ready to discard half-way into the semester. Imagine yourself in your teacher's place. To him, this is about you, in your ignorance and arrogance or at best innocence, sitting in judgment of the system to which he's devoted his professional life.

In other words, hide your views because your professor might punish you. Recognize that your professor thinks he/she knows more than you do but be confident that they're wrong. Realize that when you encounter professors in class they probably don't understand their subject even though they've devoted their lives to studying it. They might be a bit angry if you exposed them so keep you mouth shut.

Above all, resist the temptation to learn and to question your beliefs. You already know the right answer. University is not the a place for learning.

Here's my advice. It you don't want to learn then don't go to university. If your belief in creationism is really strong then don't ever take a biology class—it might turn you into an atheist and your parents will be very upset. If you need the grade, then take the class, but be prepared to fail. It takes courage to openly stand up for what you believe, especially if there might be consequences. But it's the Christian thing to do.

Most professors love it when students challenge their ideas in class. We prefer those kind of students even if they are wrong. You will never fail a course because of your ideas and beliefs as long as they don't conflict directly with scientific facts. If you believe that the Earth is 6000 years old then you will not pass a geology course or a biology, unless you lie. If you dispute the existence of junk DNA then you could get an excellent grade as long as you get your facts correct.

1. I don't think Klinghoffer has ever been to university. None of the creationist websites mention any university degrees.

According to plant geneticist, John Sanford, the human race is degenerating rapidly. It's one of the trade secrets of biology. Every population geneticists knows that it's true.

Sanford has even written a book about this trade secret: Genetic Entropy and the Mystery of the Genome

Now if humans are degenerating at the rate of 1% or so per year then this must mean that they were perfect only a short time ago—like maybe 6000 years?

Are humans doomed just as described in scripture? Yes. Is there any hope for us? Our only hope is Christ.

Interesting. Sanford doesn't exactly say exactly what Christ will do to fix all the mutations in our genome. Will He invert better DNA repair enzymes? What's taking Him so long? And why weren't we better designed to begin with?

[Hat Tip: Uncommon Descent]

This month marks the 50th edition of Carnival of Evolution. The latest version is hosted on Teaching Biology. Read it at: Carnival of Evolution 50: The Teaching Edition

Welcome to the 50th edition of the Carnival of Evolution! In keeping with the name of the blog, this edition will have an educational theme to it. The posts are categorised into modules. Each module has an introduction by me about why it’s important to learn about it, and each post has a short blurb by me on the post’s content and, if appropriate, personal comments. I include a further reading list with links to relevant books and review papers for further discussion/background information. Most of these papers are behind draconian paywalls. If you don’t have institutional access, my e-mail can be found here. Just saying.

I've got seven posts from Sandwalk on the list. That's a record for me and it means one of two things: (a) my posts are getting more interesting, or (b) they were hard up for posts this month.

The next Carnival of Evolution (August) will be hosted by The Stochastic Scientist. If you want to volunteer to host others, contact Bjørn Østman. Bjørn is always looking for someone to host the Carnival of Evolution. He would prefer someone who has not hosted before. Contact him at the Carnival of Evolution blog. You can send articles directly to him or you can submit your articles at Carnival of Evolution.

I am an atheist. What does that mean? It means that I have never seen any evidence that supernatural beings exist. I don't think the devil exists, I don't think that Zeus exists, or Thor, or Gitche Manitou. I don't believe that the god of the Bible exists.

There are thousands of gods that I don't believe in. Some of them have imaginary reputations of cruelty, some of them are supposed to be kind, and some of them are indifferent. It doesn't matter to me because the one thing they all have in common is that they don't exist.

I'm told that some people believe in gods who are supposed to be kind. Those people have trouble understanding why the world is evil. It's a problem that has spawned an entire discipline called theodicy. Bully for them. It's their problem, not mine. I don't accept their premise.

For reasons that seem incomprehensible to me, there are some atheists who really like to talk about the problem of evil as though it were a real problem. Jason Rosenhouse is one of them. You can read his latest at: The Only Reasonable Reply to the Problem of Evil. Jerry Coyne is another. See his post from yesterday at: More Sophisticated Theology: The world’s worst theodicy.

Well, maybe not all the IDiots really like me but David Klinghoffer is sure a big fan [You Go, Larry Moran!]

Just think. Imagine you're one of those undecided fence-sitters on the Darwin question that he thinks he's appealing to. Or say you're a journalist, reflexively pro-Darwin but one who's never had an occasion to follow the controversy in the past. Now something's come up in the news that touches on evolution and you figure you'll sample the arguments on both sides with a view to writing on it.

You stumble upon the blog, named in honor of Charles Darwin's famous "Sandwalk," of a University of Toronto biochemist and man of mature years who writes this way, over and over and over. He will, for example, reproduce a photo of an Internet Darwin critic with the words "I'm an IDiot" superimposed. This same biochemistry professor and Darwin advocate writes blog posts trying to defend and recommend this approach, including his favorite term "IDiot," to others. Are you impressed? That's a self-answering question.

Of course it would be different if Moran were not a guy who teaches in a relevant scientific field at a university you've heard of. If he were just another one of those pseudonyms that populate comment boxes around the Internet, and who dish out their own vicious/viscous stuff, no one would care. Much as it's distasteful to read Moran's blog (as I very rarely do), there's reason to be grateful for its existence.

Now watch, he's going to trawl the Internet for a picture of me and write "I'm an IDiot" on it and post that.

If I were purely strategic, I would say: Give us more, Larry Moran! Pour it on. Please!

Happy to oblige.

Cells require both a source of energy and a source of building blocks for synthesis of organic (carbon-containing) molecules. Some of the most interesting species are those that only need inorganic molecules to survive. They can make all their carbon compounds from carbon dioxide (CO2) by "fixing" it into more complex molecules like sugars.

These species are called "autotrophs'" The most familiar are the plants. As most of you know, plants can grow quite successfully in a glass of water (with minerals). Animals are the most obvious example of "heterotrophs," species that need to be supplied with complex organic molecules in order to survive. We can't survive on water alone. We need to get sugars and a host of other compounds from eating other (mostly dead) species.

Oscar Miller died last January. Steven McKnight, Ann Beyer, and Joseph Gall (2012) wrote up a nice tribute to their former mentor.

Those of us so fortunate as to have worked under his guidance learned how to think freely, yet rigorously, and how to dream big and gamble on new adventures. We learned from Oscar how to free ourselves from convention, yet abide by the principles of science as crafted by its most honorable pillars. We remember two pieces of advice given by Oscar: “Don't believe everything you read in the scientific literature” and “There are a thousand Ph.D. thesis projects in a mound of dung.” The latter brings to mind the famous phrase of Vannevar Bush that science is an “endless frontier.” Oscar Miller was comfortable on the frontier of the unknown; he taught us that it is only on the frontier that discoveries of significance can be made. Our community of science will miss Oscar, as will all his dear friends and family. A good man has passed.

Most of you have never heard of Oscar Miller but you've seen his work. He invented a technique for looking at genes in the electron microscope. The beauty of his technique, called "chromatin spreads" is that it shows genes in action. They are captured in the act of being transcribed and you can see the RNA being produced.

His photographs are in all the textbooks. The example shown here is ribosomal RNA genes being transcribed in the nucleolus. The "Christmas tree" structures are due to multiple transcription complexes transcribing the same gene. (Ribosomal RNA genes are very active.) The newly synthesized RNA is splayed out on either side of the DNA being transcribed. It would look like a cone inside the cell but it appears two dimensional here because it has been spread out on an electron microscope grid.

The initial transcripts are quite short but as the transcription complexes progress along the gene they get longer and longer giving rise to the Christmas tree structure. You can learn a lot from looking at these fantastic pictures. Notice that there are multiple ribosomal RNA genes arranged in tandom along the genome with relatively short spacers between them. These photos were taken before cloning and sequencing were invented so it was our among our first clues about gene organization in eukaryotes.

There's not much actual data from the 1960s that's still shown in modern textbooks. Remember Oscar Miller the next time you see his work.

McKnight, S., Beyer, A., and Gall, J. (2012) Retrospective. Oscar Miller (1925-2012). Science 335:1457. [DOI: 10.1126/science.1220681

Last week we discovered two chemically similar reactions that were catalyzed by related enzymes of the same gene family [Monday's Molecule #178]. Today's molecule is a lot more important than any of the four molecules from last week although you won't find it in most biochemistry textbooks. (Surprise! It's in my book.)

What is this molecule (IUBMB name) and why is it important?

Post your answer as a comment. I'll hold off releasing any comments for 24 hours. The first one with the correct answer wins. I will only post mostly correct answers to avoid embarrassment. The winner will be treated to a free lunch with a very famous person, or me.

There could be two winners. If the first correct answer isn't from an undergraduate student then I'll select a second winner from those undergraduates who post the correct answer. You will need to identify yourself as an undergraduate in order to win. (Put "undergraduate" at the bottom of your comment.)

Some past winners are from distant lands so their chances of taking up my offer of a free lunch are slim. (That's why I can afford to do this!)

In order to win you must post your correct name. Anonymous and pseudoanonymous commenters can't win the free lunch.

Winners will have to contact me by email to arrange a lunch date. Please try and beat the regular winners. Most of them live far away and I'll never get to take them to lunch. This makes me sad.

Comments are invisible for 24 hours. Comments are now open.

UPDATE: The molecule is 2-carboxy-3-ketoarabinitol 1,5-bisphosphate, an intermediate in the reaction catalyzed by rubisco (ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carbozylase-oxygenase). This is the main enzyme responsible for carbon dioxide fixation in plants and one of the most enzymes on the planet.

This week's winners are Bill Chaney and Raul A. Félix de Sousa.

Winners

Nov. 2009: Jason Oakley, Alex Ling

Oct. 17: Bill Chaney, Roger Fan

Oct. 24: DK

Oct. 31: Joseph C. Somody

Nov. 7: Jason Oakley

Nov. 15: Thomas Ferraro, Vipulan Vigneswaran

Nov. 21: Vipulan Vigneswaran (honorary mention to Raul A. Félix de Sousa)

Nov. 28: Philip Rodger

Dec. 5: 凌嘉誠 (Alex Ling)

Dec. 12: Bill Chaney

Dec. 19: Joseph C. Somody

Jan. 9: Dima Klenchin

Jan. 23: David Schuller

Jan. 30: Peter Monaghan

Feb. 7: Thomas Ferraro, Charles Motraghi

Feb. 13: Joseph C. Somody

March 5: Albi Celaj

March 12: Bill Chaney, Raul A. Félix de Sousa

March 19: no winner

March 26: John Runnels, Raul A. Félix de Sousa

April 2: Sean Ridout

April 9: no winner

April 16: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

April 23: Dima Klenchin, Deena Allan

April 30: Sean Ridout

May 7: Matt McFarlane

May 14: no winner

May 21: no winner

May 29: Mike Hamilton, Dmitri Tchigvintsev

June 4: Bill Chaney, Matt McFarlane

June 18: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

June 25: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

July 2: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

July 16: Sean Ridout, William Grecia

July 23: Raul A. Félix de Sousa

July 30: Bill Chaney and Raul A. Félix de Sousa

I can't believe it was almost five years ago that I posted a quotation from Stephen Fry on the differences between dinner conversations in Britain and America [Two Cultures].

Here it is again because it's relevant to our discussion about IDiots. It's from: Getting Overheated (Nov. 19, 2007).

We must begin with a few round truths about myself: when I get into a debate I can get very, very hot under the collar, very impassioned, and I dare say, very maddening, for once the light of battle is in my eye I find it almost impossible to let go and calm down. I like to think I’m never vituperative or too ad hominem but I do know that I fall on ideas as hungry wolves fall on strayed lambs and the result isn’t always pretty. This is especially dangerous in America. I was warned many, many years ago by the great Jonathan Lynn, co-creator of Yes Minister and director of the comic masterpiece My Cousin Vinnie, that Americans are not raised in a tradition of debate and that the adversarial ferocity common around a dinner table in Britain is more or less unheard of in America. When Jonathan first went to live in LA he couldn’t understand the terrible silences that would fall when he trashed an statement he disagreed with and said something like “yes, but that’s just arrant nonsense, isn’t it? It doesn’t make sense. It’s self-contradictory.” To a Briton pointing out that something is nonsense, rubbish, tosh or logically impossible in its own terms is not an attack on the person saying it – it’s often no more than a salvo in what one hopes might become an enjoyable intellectual tussle. Jonathan soon found that most Americans responded with offence, hurt or anger to this order of cut and thrust. Yes, one hesitates ever to make generalizations, but let’s be honest the cultures are different, if they weren’t how much poorer the world would be and Americans really don’t seem to be very good at or very used to the idea of a good no-holds barred verbal scrap. I’m not talking about inter-family ‘discussions’ here, I don’t doubt that within American families and amongst close friends, all kinds of liveliness and hoo-hah is possible, I’m talking about what for good or ill one might as well call dinner-party conversation. Disagreement and energetic debate appears to leave a loud smell in the air.

Have you ever been at a social gathering and heard someone proclaim, somewhat proudly, that they just don't "get" math? They dropped it in high school as soon as they could. If so, you probably resisted telling them how sorry you are that they are stupid and you probably avoided getting into a discussion about people who say the same thing about history or literature. You know that those same people would be appalled to hear you say that you don't "get" the arts and dropped them as soon as you could.

If Andrew Hacker has his way, people who can't pass a simple math course will never have to apologize again. He proposes, in the New York Times, no less, to eliminate algebra from high school [Is Algebra Necessary?]. (Andrew Hacker is a former professor of political science.)