Most Sandwalk readers will recognize Mattick as one of the few remaining vocal opponents of junk DNA. He is probably best known for his dog-ass plot but this is only one of the ways he misrepresents science.

More Recent Comments

Friday, September 27, 2024

John Mattick's seminar at the University of Toronto

Friday, March 15, 2024

Nils Walter disputes junk DNA: (9) Reconciliation

I'm discussing a recent paper published by Nils Walter (Walter, 2024). He is arguing against junk DNA by claiming that the human genome contains large numbers of non-coding genes.

This is the ninth and last post in the series. I'm going to discuss Walker's view on how to tone down the dispute over the amount of junk in the human genome. Here's a list of the previous posts.

- Nils Walter disputes junk DNA: (1) The surprise

- Nils Walter disputes junk DNA: (2) The paradigm shaft

- Nils Walter disputes junk DNA: (3) Defining 'gene' and 'function'

- Nils Walter disputes junk DNA: (4) Different views of non-functional transcripts

- Nils Walter disputes junk DNA: (5) What does the number of transcripts per cell tell us about function?

- Nils Walter disputes junk DNA: (6) The C-value paradox

- Nils Walter disputes junk DNA: (7) Conservation of transcribed DNA

- Nils Walter disputes junk DNA: (8) Transcription factors and their binding sites

"Conclusion: How to Reconcile Scientific Fields"

Walter concludes his paper with some thoughts on how to deal with the controversy going forward. I'm using the title that he choose. As you can see from the title, he views this as a squabble between two different scientific fields, which he usually identifies as geneticists and evolutionary biologists versus biochemists and molecular biologists. I don't agree with this distinction. I'm a biochemist and molecular biologist, not a geneticist or an evolutionary biologist, and still I think that many of his arguments are flawed.

Let's see what he has to say about reconciliation.

Science thrives from integrating diverse viewpoints—the more diverse the team, the better the science.[107] Previous attempts at reconciling the divergent assessments about the functional significance of the large number of ncRNAs transcribed from most of the human genome by pointing out that the scientific approaches of geneticists, evolutionary biologists and molecular biologists/biochemists provide complementary information[42] was met with further skepticism.[74] Perhaps a first step toward reconciliation, now that ncRNAs appear to increasingly leave the junkyard,[35] would be to substitute the needlessly categorical and derogative word RNA (or DNA) “junk” for the more agnostic and neutral term “ncRNA of unknown phenotypic function”, or “ncRNAupf”. After all, everyone seems to agree that the controversy mostly stems from divergent definitions of the term “function”,[42, 74] which each scientific field necessarily defines based on its own need for understanding the molecular and mechanistic details of a system (Figure 3). In addition, “of unknown phenotypic function” honors the null hypothesis that no function manifesting in a phenotype is currently known, but may still be discovered. It also allows for the possibility that, in the end, some transcribed ncRNAs may never be assigned a bona fide function.

First, let's take note of the fact that this is a discussion about whether a large percentage of transcripts are functional or not. It is not about the bigger picture of whether most of the genome is junk in spite of the fact that Nils Walter frames it in that manner. This becomes clear when you stop and consider the implications of Walter's claim. Let's assume that there really are 200,000 functional non-coding genes in the human genome. If we assume that each one is about 1000 bp long then this amounts to 6.5% of the genome—a value that can easily be accommodated within the 10% of the genome that's conserved and functional.

Now let's look at how he frames the actual disagreement. He says that the groups on both sides of the argument provide "complementary information." Really? One group says that if you can delete a given region of DNA with no effect on the survival of the individual or the species then it's junk and the other group says that it still could have a function as long as it's doing something like being transcribed or binding a transcription factor. Those don't look like "complimentary" opinions to me.

His first step toward reconciliation starts with "now that ncRNAs appear to increasingly leave the junkyard." That's not a very conciliatory way to start a conversation because it immediately brings up the question of how many ncRNAs we're talking about. Well-characterized non-coding genes include ribosomal RNA genes (~600), tRNA genes (~200), the collection of small non-coding genes (snRNA, snoRNA, microRNA, siRNA, PiWi RNA)(~200), several lncRNAs (<100), and genes for several specialized RNAs such as 7SL and the RNA component of RNAse P (~10). I think that there are no more than 1000 extra non-coding genes falling outside these well-known examples and that's a generous estimate. If he has evidence for large numbers that have left the junkyard then he should have presented it.

Walter goes on to propose that we should divide non-coding transcripts into two categories; those with well-characterized functions and "ncRNA of unknown function." That's ridiculous. That is not a "agnostic and neutral term." It implies that non-conserved transcripts that are present at less that one copy per cell could still have a function in spite of the fact that spurious transcription is well-documented. In fact, he basically admits this interpretation at the end of the paragraph where he says that using this description (ncRNA of unknown function) preserves the possibility that a function might be discovered in the future. He thinks this is the "null hypothesis."

The real null hypothesis is that a transcript has no function until it can be demonstrated. Notice that I use the word "transcript" to describe these RNAs instead of "ncRNA" or "ncRNA of unknown phenotypic function." I don't think we lose anything by using the word "transcript."

Walter also address the meaning of "function" by claiming that different scientific fields use different definitions as though that excuses the conflict. But that's not an accurate portrayal of the problem. All scientists, no matter what field they identify with, are interested in coming up with a way of identifying functional DNA. There are many biochemists and molecular biologists who accept the maintenance definition as the best available definition of function. As scientists, they are more than willing to entertain any reasonable scientific arguments in favor of a different definition but nobody, including Nils Walter, has come up with such arguments.

Now let's look at the final paragraph of Walter's essay.

Most bioscientists will also agree that we need to continue advancing from simply cataloging non-coding regions of the human genome toward characterizing ncRNA functions, both elementally and phenotypically, an endeavor of great challenge that requires everyone's input. Solving the enigma of human gene expression, so intricately linked to the regulatory roles of ncRNAs, holds the key to devising personalized medicines to treat most, if not all, human diseases, rendering the stakes high, and unresolved disputes counterproductive.[108] The fact that newly ascendant RNA therapeutics that directly interface with cellular RNAs seem to finally show us a path to success in this challenge[109] only makes the need for deciphering ncRNA function more urgent. Succeeding in this goal would finally fulfill the promise of the human genome project after it revealed so much non-protein coding sequence (Figure 1). As a side effect, it may make updating Wikipedia and encyclopedia entries less controversial.

I agree that it's time for scientists to start identifying those transcripts that have a true function. I'll go one step further; it's time to stop pretending that there might be hundreds of thousands of functional transcripts until you actually have some data to support such a claim.

I take issue with the phrase "solving the enigma of human gene expression." I think we already have a very good understanding of the fundamental mechanisms of gene expression in eukaryotes, including the transitions between open and closed chromatin domains. There may be a few odd cases that deviate from the norm (e.g. Xist) but that hardly qualifies as an "enigma." He then goes on to say that this "enigma" is "intricately linked to the regulatory roles of ncRNAs" but that's not a fact, it's what's in dispute and why we have to start identifying the true function (if any) of most transcripts. Oh, and by the way, sorting out which parts of the genome contain real non-coding genes may contribute to our understanding of genetic diseases in humans but it won't help solve the big problem of how much of our genome is junk because mutations in junk DNA can cause genetic diseases.

Sorting out which transcripts are functional and which ones are not will help fill in the 10% of the genome that's functional but it will have little effect on the bigger picture of a genome that's 90% junk.

We've known that less than 2% of the genome codes for proteins since the late 1960s—long before the draft sequence of the human genome was published in 2001—and we've known for just as long that lots of non-coding DNA has a function. It would be helpful if these facts were made more widely known instead of implying that they were only dscovered when the human genome was sequenced.

Once we sort out which transcripts are functional, we'll be in a much better position to describe the all the facts when we edit Wikipedia articles. Until that time, I (and others) will continue to resist the attempts by the students in Nils Walter's class to remove all references to junk DNA.

Walter, N.G. (2024) Are non‐protein coding RNAs junk or treasure? An attempt to explain and reconcile opposing viewpoints of whether the human genome is mostly transcribed into non‐functional or functional RNAs. BioEssays:2300201. [doi: 10.1002/bies.202300201]

Thursday, March 14, 2024

Nils Walter disputes junk DNA: (8) Transcription factors and their binding sites

I'm discussing a recent paper published by Nils Walter (Walter, 2024). He is arguing against junk DNA by claiming that the human genome contains large numbers of non-coding genes.

This is the seventh post in the series. The first one outlines the issues that led to the current paper and the second one describes Walter's view of a paradigm shift/shaft. The third post describes the differing views on how to define key terms such as 'gene' and 'function.' In the fourth post I discuss his claim that differing opinions on junk DNA are mainly due to philosophical disagreements. The fifth, sixth, and seventh posts address specific arguments in the junk DNA debate.

- Nils Walter disputes junk DNA: (1) The surprise

- Nils Walter disputes junk DNA: (2) The paradigm shaft

- Nils Walter disputes junk DNA: (3) Defining 'gene' and 'function'

- Nils Walter disputes junk DNA: (4) Different views of non-functional transcripts

- Nils Walter disputes junk DNA: (5) What does the number of transcripts per cell tell us about function?

- Nils Walter disputes junk DNA: (6) The C-value paradox

- Nils Walter disputes junk DNA: (7) Conservation of transcribed DNA

Friday, February 09, 2024

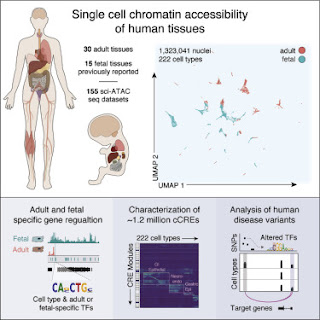

Open and closed chromatin domains (and epigenetics)

Gene expression in eukaryotes is influenced by the state of chromatin. Tightly packed nucleosomes inhibit the binding of transcription factors and RNA polymerase so that genes in these regions are "repressed." From time to time these regions loosen up a bit allowing access to transcription complexes and subsequent transcription.

The tightly packed regions are known as closed domains and the accessible regions are open domains. Some authors add an intermediate domain called a permissive domain. This model of eukaryotic gene expression has been around for 50 years and the important mechanisms controlling the switch were worked out in the 1980s. I found a recent review that covers this issue in the context of epigenetics and the image below comes from that paper (Klemm et al., 2019).

Tuesday, September 05, 2023

John Mattick's new dog-ass plot (with no dog)

Mattick, J.S. (2023) RNA out of the mist. TRENDS in Genetics 39:187-207. [doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2022.11.001,/p>

RNA has long been regarded primarily as the intermediate between genes and proteins. It was a surprise then to discover that eukaryotic genes are mosaics of mRNA sequences interrupted by large tracts of transcribed but untranslated sequences, and that multicellular organisms also express many long ‘intergenic’ and antisense noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs). The identification of small RNAs that regulate mRNA translation and half-life did not disturb the prevailing view that animals and plant genomes are full of evolutionary debris and that their development is mainly supervised by transcription factors. Gathering evidence to the contrary involved addressing the low conservation, expression, and genetic visibility of lncRNAs, demonstrating their cell-specific roles in cell and developmental biology, and their association with chromatin-modifying complexes and phase-separated domains. The emerging picture is that most lncRNAs are the products of genetic loci termed ‘enhancers’, which marshal generic effector proteins to their sites of action to control cell fate decisions during development.

Wednesday, February 15, 2023

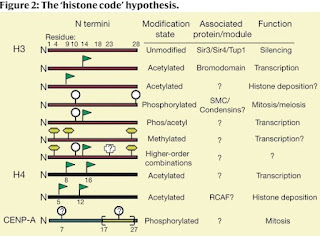

David Allis (1951 - 2023) and the "histone code"

C. David Allis died on January 8, 2023. You can read about his history of awards and accomplishments in the Nature obituary with the provocative subtitle Biologist who revolutionized the chromatin and gene-expression field. This refers to his work on histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and his ideas about the histone code.

The key paper on the histone code is,

Strahl, B. D., and Allis, C. D. (2000) The language of covalent histone modifications. Nature, 403:41-45. [doi: 10.1038/47412]

Histone proteins and the nucleosomes they form with DNA are the fundamental building blocks of eukaryotic chromatin. A diverse array of post-translational modifications that often occur on tail domains of these proteins has been well documented. Although the function of these highly conserved modifications has remained elusive, converging biochemical and genetic evidence suggests functions in several chromatin-based processes. We propose that distinct histone modifications, on one or more tails, act sequentially or in combination to form a ‘histone code’ that is, read by other proteins to bring about distinct downstream events.

They are proposing that the various modifications of histone proteins can be read as a sort of code that's recognized by other factors that bind to nucleosomes and regulation gene expression.

This is an important contribution to our understanding of the relationship between chromatin structure and gene expression. Nobody doubts that transcription is associated with an open form of chromatin that correlates with demethylation of DNA and covalent modifications of histone and nobody doubts that there are proteins that recognize modified histones. However, the key question is what comes first; the binding of transcription factors followed by changes to the DNA and histones, or do the changes to DNA and histones open the chromatin so that transcription factors can bind? These two models are referred to as the histone code model and the recruitment model.

Strahl and Allis did not address this controversy in their original paper; instead, they concentrated on what happens after histones become modified. That's what they mean by "downstream events." Unfortunately, the histone code model has been appropriated by the epigenetics cult and they do not distinguish between cause and effect. For example,

The “histone code” is a hypothesis which states that DNA transcription is largely regulated by post-translational modifications to these histone proteins. Through these mechanisms, a person’s phenotype can change without changing their underlying genetic makeup, controlling gene expression. (Shahid et al. (2022)

The language used by fans of epigenetics strongly implies that it's the modification of DNA and histones that is the primary event in regulating gene expression and not the sequence of DNA. The recruitment model states that regulation is primarily due to the binding of transcription factors to specific DNA sequences that control regulation and then lead to the epiphenomenon of DNA and histone modification.

The unauthorized expropriation of the histone code hypothesis should not be allowed to diminish the contribution of David Allis.

Wednesday, June 29, 2022

The Function Wars Part XII: Revising history and defending ENCODE

I'm very disappointed in scientists and philosophers who try to defend ENCODE's behavior on the grounds that they were using a legitimate definition of function. I'm even more annoyed when they deliberately misrepresent ENCODE's motive in launching the massive publicity campaign in 2012.

Here's another new paper on the function wars.

Ratti, E. and Germain, P.-L. (2021) A Relic of Design: Against Proper Functions in Biology. Biology & Philosophy 37:27. [doi: 10.1007/s10539-022-09856-z]

The notion of biological function is fraught with difficulties - intrinsically and irremediably so, we argue. The physiological practice of functional ascription originates from a time when organisms were thought to be designed and remained largely unchanged since. In a secularized worldview, this creates a paradox which accounts of functions as selected effect attempt to resolve. This attempt, we argue, misses its target in physiology and it brings problems of its own. Instead, we propose that a better solution to the conundrum of biological functions is to abandon the notion altogether, a prospect not only less daunting than it appears, but arguably the natural continuation of the naturalisation of biology.

Friday, April 01, 2022

Illuminating dark matter in human DNA?

A few months ago, the press office of the University of California at San Diego issued a press release with a provocative title ...

Illuminating Dark Matter in Human DNA - Unprecedented Atlas of the "Book of Life"

The press release was posted on several prominent science websites and Facebook groups. According to the press release, much of the human genome remains mysterious (dark matter) even 20 years after it was sequenced. According to the senior author of the paper, Bing Ren, we still don't understand how genes are expressed and how they might go awry in genetic diseases. He says,

A major reason is that the majority of the human DNA sequence, more than 98 percent, is non-protein-coding, and we do not yet have a genetic code book to unlock the information embedded in these sequences.

We've heard that story before and it's getting very boring. We know that 90% of our genome is junk, about 1% encodes proteins, and another 9% contains lots of functional DNA sequences, including regulatory elements. We've known about regulatory elements for more than 50 years so there's nothing mysterious about that component of noncoding DNA.

Wednesday, June 09, 2021

Let's analyze the Newsweek lab leak conspiracy theory article

Lots of people have been sucked in to the lab leak conspiracy theory based on reporting in newspapers and magazines. One of the widely-cited sources is an article published in Newsweek on June 2, 2021. The focus of the article is on How Amateur Sleuths Broke the Wuhan Lab Story and Embarrassed the Media. Those "amateur sleuths" go by the name "Decentralized Radical Autonomous Search Team Investigating COVID-19" or DRASTIC. I'm not interested in them; I'm interested in scientific facts so let's look at all of the so-called "facts" in the Newsweek article. I'll leave it up to you, dear reader, to judge whether the media should be embarrassed by this story.

Newsweek statment #1: Thanks to DRASTIC, we now know that the Wuhan Institute of Virology had an extensive collection of coronaviruses gathered over many years of foraging in the bat caves, and that many of them—including the closest known relative to the pandemic virus, SARS-CoV-2—came from a mineshaft where three men died from a suspected SARS-like disease in 2012.

Some of this is correct. The WIV scientists and their collaborators have been collecting samples from bats all over China and Indochina for several years and many of them have been examined for the presence of coronaviruses. WIV scientists routinely sampled bats from the Yunnan mine cave from 2012 to 2015 after they were informed that four people had been admitted to hospital with severe respiratory disease in 2012 (one of them died). The workers tested negative for Ebola, Nipah virus, and coronavirus so the scientists were looking for a likely unknown virus that caused the infection. (The serum samples were subsequently tested for SARS-CoV-2 and they were negative.)

Several coronaviruses were detected in the bat samples based on short PCR sequences (370 bp) from the RdRp gene and they were classified as either alphacoronaviruses or betacoronaviruses. The data was published in 2016 (Ge et al., 2016) and the sequences were deposited in GenBank in 2016. Improvements in sequencing technology in 2018 prompted a re-examination of those bat samples and an almost full-length sequence of a betacoronavirus was obtained (missing the 5′ and 3′ ends). This virus was named RaTG13 and one of the short GenBank sequences identified as BtCoV/4491 (Accession #KP876546) comes from that virus (Zhou et al., 2020 Addendum).

The bat virus is RaTG13 and it is 96% similar in sequence to SARS-CoV-2—that means that they probably shared a common ancestor about 50 years ago (Zhou et al. 2020). The sequence was deposited in GenBank as Accession #Mn996532. There are parts of SARS-CoV-2 that are not closely related to RaTG13 and this includes the spike protein gene, which is essential for infecting humans. The spike gene sequence is most closely related to a coronavirus from pangolins, Pangolin-Cov.

The data is consistent with a recombination event between different strains of coronaviruses giving rise to SARS-CoV-2 or its immediate ancestors. Such recombinations are a common feature of coronavirus propagation in various animals, including bats. What's clear is that none of the currently known coronavirus sequences could possibly be the ancestors of SARS-CoV-2 so the hunt is on to locate those viruses.

Recently, the scientists at WIV and their collaboratore at the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing looked at some of the other samples from bat anal swabs collected in Yunnan in 2015. This in depth analysis was prompted by the discovery of SARS-CoV-2 and the pandemic. They found a number of other bat coronavisus sequences and some of them were more closely related to SARS-CoV-2 in the ORF1b regions but not in other parts of the genome. Again, this is consistent with frequent recombination events that have been documented over the past few decades. Surprisingly, some of these new bat coronavisuses were able to use the bat angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as a receptor, but they did not bind to human ACE2. (These assays take a lot of time and effort.) This and other data show that the evolution of ACE2 binding can occur in bats giving rise to a generalist virsus, SARS-CoV-2, than can bind to ACE2 from many different species. (MacLean et al., 2021; Guo et al., 2021).

A group of scientists from France, United States, Vietnam, and Cambodia looked at bat samples that were collected in Cambodia in 2010 and found coronaviruses from another species of bats that were cloesly related to SARS-CoV-2 across most of the genome except for a small region of the spike protein gene. In some parts of the genome (ORF1a and ORF8) these viruses were more closely related to SARS-CoV-2 than RATG13 (Hu et al. 2021). The evolutionary history of the Cambodian viruses indicate that they are mosaic viruses due to recombination events. This data indicates that SARS-CoV-2 related viruses are found in Southeast Asia as well as China—that's signficant since pangolins are only found in Southeast Asia and not in China.

SARS-CoV-2-like viruses have also been found in Thailand (Wacharapluesadee et al., 2021).

A group centered in Taian, China, has recently examined coronaviruses from bats at the botanical garden in Mengal county in Yunnan. They have identified four additional SARS-CoV-2 related viruses including one, RpYN06, that is the closest relative to SARS-CoV-2 outside of the spike gene. This is now the leading candidate for the "backbone" that might have given rise to the pandemic virus (Zhou et al., 2021).

CONCLUSION: The Newsweek statement is not wrong but it is highly misleading. The WIV labs had bat samples that contained coronaviruses but so did lots of labs all over the world. In that sense, these labs have an "extensive collection of coronaviruses" but they are stored in bat poop at -80° C! They identified two coronavirus, RaTG13 and RmYN02, by sequencing PCR fragments but the sequences were not complete. It's misleading for Newsweek to imply that the WIV labs had an RaTG13 coronavirus in their labs because that implies that they were working with active viruses. It's true that the RaTG13 virus came from a place where several workers had gotten sick with respiratory disease a few years before the sample was collected. One of these men died (not three) but none of the patients tested positive for coronavirus.

Newsweek statement #2: We know that the WIV was actively working with these viruses, using inadequate safety protocols, in ways that could have triggered the pandemic, and that the lab and Chinese authorities have gone to great lengths to conceal these activities.

CONCLUSION: This is misleading. As far as I know, the scientists are WIV were not actively working with the RaTG13 virus because they had never isolated that virus. Furthermore, it's almost impossible to create SARS-CoV-2 from RaTG13 [Could scientists use the bat coronavirus RaTG13 to engineer SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, in a lab?]. They were working with other bat coronaviruses but none of them were closely related to SARS-CoV-2 so it's extremely misleading to imply that the escape of these viruses could have triggered the pandemic. They were not using inadequate safety protocols because all of the work with bat coronaviruses was carried out in level 2 labs, exactly as required. There's no evidence that the scientists at the WIV labs have concealed anything. You can only accuse someone of concealing something if you have strong evidence that they did something that they deny doing.

Newsweek statement #3: We know that the first cases appeared weeks before the outbreak at the Huanan wet market that was once thought to be ground zero.

CONCLUSION: This is correct. Chinese scientists and health workers identified a number of earlier cases that appear to be unrelated to the seafood market and they published their results in scientific journals over a year ago. They now conclude that the virus was circulating in the Wuhan population for more than a month before the superspreader event at the market ignited the pandemic. This appears to be a case where Newsweek trusts the work of Chinese scientists.

Newsweek statement #4: The Newsweek article talks a lot about the DRASTIC group as though they have uncovered a huge conspriacy theory. One of their "discoveries" relates to the bat coronavirus RaTG13 that's first mentioned in the paper where the SARS-CoV-2 sequence was published. Here's what Newsweek wrote: "The paper was vague about where RaTG13 had come from. It didn't say exactly where or when RaTG13 had been found, just that it had previously been detected in a bat in Yunnan Province, in southern China.

The paper aroused Deigin's suspicions. He wondered if SARS-CoV-2 might have emerged through some genetic mixing and matching from a lab working with RaTG13 or related viruses. His post was cogent and comprehensive. The Seeker posted Deigin's theory on Reddit, which promptly suspended his account permanently."

CONCLUSION: This is written like it's a big mystery that was uncovered by some clever sleuthing. It's true that the origin of RaTG13 was not discussed in the SARS-CoV-2 paper in January 2020 other than to say that it was found in a bat in Yunnan. I assume that the authors didn't think it was important (and still don't). The origin was explained in November 2020 in an Addendum to the Nature article (Zhou et al., 2020, Addendum). It was one of the viruses discoverd in the bats from the Yunnan mine cave and a partial sequence had been published earlier (Ge et al., 2016). It's not particulary close to SARS-CoV-2 and there's no reason to speculate that it was artificially created unless you are trying to create a conspiracy.

Newsweek statement #5: The key facts quickly came together. The genetic sequence for RaTG13 perfectly matched a small piece of genetic code posted as part of a paper written by Shi Zhengli years earlier, but never mentioned again. The code came from a virus the WIV had found in a Yunnan bat. Connecting key details in the two papers with old news stories, the DRASTIC team determined that RaTG13 had come from a mineshaft in Mojiang County, in Yunnan Province, where six men shoveling bat guano in 2012 had developed pneumonia. Three of them died. DRASTIC wondered if that event marked the first cases of human beings being infected with a precursor of SARS-CoV-2—perhaps RaTG13 or something like it.

In a profile in Scientific American, Shi Zhengli acknowledged working in a mineshaft in Mojiang County where miners had died. But she avoided connecting it to RaTG13 (an omission she had made in her scientific papers as well), claiming that a fungus in the cave had killed the miners.

This reads just like a typical conspiracy theory where "clever" sleuths (i.e. internet anateurs) uncover information that was hidden or covered up by those they are accusing. The origin of RaTG13 was explained in an addendum to the publication of the SARS-CoV-2 sequence in February 2020. The addendum was added in November 2020 in reponse to questions about the origin of RaTG13 but that information was widely known. The sequence of a short fragment of this virus was obtained earlier as explained above.

The WIV scientists were very concerned about the Yunnan mine workers because they had symptoms that were similar to those of SARS patients and that's why they tested serum from the patients. They were negative for all the viruses, including the original SARS-CoV-1. (The serum is also negative for SARS-CoV-2.) The WIV scientists were worried that the infections were due to an unknown virus that could cause a pandemic so they went back to the mine every year to collect samples from the bats. The RaTG13 sequence came from one of those samples but by then the scientists knew that there was no connection between the bat coronaviruses and the sick mine workers. (They were probably disappointed at the lack of connection because they were looking for the cause of the 2002 SARS outbreak.)

The WIV scientists now believe that the Yunnan mine workers had contracted a fungal infection from the fungus growing on the bat guano. There is no reason to connect RaTG13 to the mine workers because it's been known for many years that the workers were not infected with any coronavirus.

The RaTG13 virus is from the bat species Rhinolophus affinis (hence the designation "Ra") but up until the beginning of the pandemic the WIV scientists were much more interested in another cave in Yunnan populated by a number of different species. They reported that this cave represents the most diverse collection of bat coronaviruses in the world. Most of the ones that are SARS-like were from a different species of bat, Rhinolophus sinicus and many of these bound the same ACE2 receptor that SARS-CoV-1 used—the same one used by the more recent SARS-CoV-2 (Hu et al. 2017; Cui et al., 2019).

CONCLUSION: The Newsweek article is repeating innuendos and conspiracies that have been discredited in the past. The DRASTIC team is deliberately making up connections between coroanvirus and the mine workers but all of the data shows that there's no direct connection. It just happened that one of the bat coronaviruses collected in that mine happened to be the one closest to SARS-CoV-2, in part because that was a pretty extensive collection. The RaTG13 sequence is not similar enough to SAS-CoV-2 to be the direct ancestor and, besides, there are now known to be other virus sequences from as far away as Cambodia that are just as similar to SARS-CoV-2.

Newsweek statement #6: That explanation didn't sit well with the DRASTIC group. They suspected a SARS-like virus, not a fungus, had killed the miners and that, for whatever reason, the WIV was trying to hide that fact. It was a hunch, and they had no way of proving it.

At this point, The Seeker revealed his research powers to the group. In his online explorations, he'd recently discovered a massive Chinese database of academic journals and theses called CNKI. Now he wondered if somewhere in its vast circuitry might be information on the sickened miners.

Working through the night at his bedside table on phone and laptop, fueled by chai and using Chinese characters with the help of Google Translate, he plugged in "Mojiang"—the county where the mine was located—in combination with every other word he could think of that might be relevant, instantly translating each new flush of results back to English. "Mojiang + pneumonia"; "Mojiang + WIV"; "Mojiang + bats"; "Mojiang + SARS." Each search brought back thousands of results and half a dozen different databases for journals, books, newspapers, master's theses, doctoral dissertations. He combed through these results, night after night, but never found anything useful. When he ran out of energy, he broke for arcade games and more chai.

He was on the verge of calling it quits, he says, when he struck gold: a 60-page master's thesis written by a student at Kunming Medical University in 2013 titled "The Analysis of 6 Patients with Severe Pneumonia Caused by Unknown Viruses." In exhaustive detail, it described the conditions and step-by-step treatment of the miners. It named the suspected culprit: "Caused by SARS-like [coronavirus] from the Chinese horseshoe bat or other bats."

CONCLUSION: Move along folks; there's nothing to see here. The WIV scientists suspected that the miners were infected with an unknown virus and that's why they were concerned in 2012. They knew that coronavirus wasn't responsible and neither was any other known virus. This is why they went back every year to test the bats in the mine shaft. The know that the stored serum from these workers is negative for SARS-CoV-2, which is not a surprise. They now suspect that the mine workers had contracted a fungl infection and not a viral infection. It's not particulary surprising that a student reported the suspected cause of the symptoms back in the beginning of the investigation.

Newsweek statement #7: Ribera was responsible for solving another piece of the RaTG13 puzzle. Had the WIV been actively working on RaTG13 during the seven years since they discovered it? Peter Daszak said no: they had never used the virus because it wasn't similar enough to the original SARS. "We thought it's interesting, but not high-risk," he told Wired. "So we didn't do anything about it and put it in the freezer."

Ribera disproved that account. When a new science paper on genetics is published, the authors must upload the accompanying genetic sequences to an international database. By examining some metadata tags that had been accidentally uploaded by the WIV along with its genetic sequences for RaTG13, Ribera discovered that scientists at the lab had indeed been actively studying the virus in 2017 and 2018—they hadn't stuck it in a freezer and forgotten about it, after all.

I don't know what this means. The WIV scientists sequenced a bit of what turned out to be the RaTG13 virus when they catagorized all the other viruses back in 2012-2015 (Ge et al. 2016). They then completed an almost whole genome sequence later on in 2018 when their sequencing techniques improved. It's important keep in mind that the WIV never worked with the RaTG13 virus as emphasized by Frutos et al. (2021): "One must remember that SARS-CoV-2 was never found in the wild and that RaTG13 does not exist as a real virus but instead only as a sequence in a computer. It is a virtual virus which thus cannot leak from a laboratory." 1

CONCLUSION: The scientists at WIV were "working with" the RaTG13 PCR fragments in 2017 and 2018 as they assembled the whole genome sequence. They also assembled the sequences of seveal other viruses at the same time. To say that they were "actively studying" the virus is very misleading and to accuse Peter Daszek of lying is irresponsible.

Newsweek statement #8: In fact, the WIV had been intensely interested in RaTG13 and everything else that had come from the Mojiang mineshaft. From his giant Sudoku puzzle, Ribera determined that they made at least seven different trips to the mine, over many years, collecting thousands of samples. Ribera's guess is that their technology had not been good enough in 2012 and 2013 to find the virus that had killed the miners, so they kept going back as the techniques improved.

He also made a bold prediction. Cross-referencing snippets of information from multiple sources, Ribera guessed, in a Twitter thread dated August 1, 2020, that a cluster of eight SARS-related viruses mentioned briefly in an obscure section of one WIV paper had actually also come from the Mojiang mine. In other words, they hadn't found one relative of SARS-CoV-2 in that mineshaft; they'd found nine. In November 2020, Shi Zhengli confirmed many of DRASTIC's suspicions about the Mojiang cave in an addendum to her original paper on RaTG13 and in a talk in February 2021.

The mine shaft is located in Mojiang county, Yunnan—a map of the location was published in Ge et al. (2016). It contains six different bat species and many of them were infected with coronaviruses. The WIV scientists collected many samples over a number of years in order to determine the phylogeny of the viruses and which species were infected. They also did longitudinal studies to see if the different virus variants changed over time and to see if the infection rates of the various bat species were different from year to year. They also wanted to see if they could detect recombinations between different virus groups.

They obtained 152 partial sequences and then picked 12 of them for more detailed analysis in order to construct a phylogenetic tree from 816 bp of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) gene. Anyone can read the Ge et al. (2016) paper to see why they were doing these experiments. There's nothing mysterious or unusual about their approach. It's the same one they took with the viruses from the other site (cave) in Yunnan where they identified the two bat coronaviruses that are most closely related to the original SARS virus (Ge et al., 2013) (see: SARS ouotbreak linked to Chinese bat cave)

CONCLUSION: The Newsweek article is making a huge mountain out of a molehill and it's misrepresenting the work of the "amateur sleuths." It's not a secret or a mystery that the WIV scientists were studying the coronaviruses from the mine shaft. That's what they do and they publish in journals that are easy to access.

Newsweek statement #9: "Other databases yielded other clues. In the WIV's grant applications and awards, The Seeker found detailed descriptions of the Institute's research plans, and they were damning: Projects were underway to test the infectivity of novel SARS-like viruses they'd discovered in human cells and in lab animals, to see how they might mutate as they crossed species, and to genetically recombine pieces of different viruses—all being done at woefully inadequate biosecurity levels. All the elements for a disaster were on hand."

CONCLUSION: It's true that the WIV scientists were looking at SARS-like coronavisuses and they were testing for infectivity in humanized mouse cells. The goal was to look for new coronaviruses that could bind ACE2 and they found quite a few of them. In many cases, they expressed the spike protein in recombinant viruses and plasmids just as you would expect them to do if they were looking for the source of the original SARS virus (SARS-CoV-1). All this is described in their grant applications and in their publications. Looks like they didn't make much of an attempt to hide this research. All the experiments were done under the appropriate biosafety measures as specified by international inspectors who visited the lab on several occasions. None of this has anything to do with the pandemic because they were not working with SARS-CoV-2 or any close relative.

The rest of the Newsweek article consists mostly of praise for the DRASTIC heros and the excellent work they have done in uncovering a huge conspiracy to cover up the fact that the WIV scientists started a pandemic. However, one embarrassing fact remains: there is not a shred of evidence that the lab was working with SARS-CoV-2 before the pandemic started. In the absence of such evidence it is irresponsible to accuse these reputable scientists of lying.

1. One could quibble slightly about the accuracy of this statment since there might be RaTG13 virus particles in the bat fecal samples that are stored in the -80°C freezer.

Cui, J., Li, F. and Shi, Z.-L. (2019) Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nature Reviews Microbiology 17:181-192. doi: [doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0118-9]

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) are two highly transmissible and pathogenic viruses that emerged in humans at the beginning of the 21st century. Both viruses likely originated in bats, and genetically diverse coronaviruses that are related to SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV were discovered in bats worldwide. In this Review, we summarize the current knowledge on the origin and evolution of these two pathogenic coronaviruses and discuss their receptor usage; we also highlight the diversity and potential of spillover of bat-borne coronaviruses, as evidenced by the recent spillover of swine acute diarrhoea syndrome coronavirus (SADS-CoV) to pigs.

Hu, V., Delaune, D., Karlsson, E.A., Hassanin, A., Tey, P.O., Baidaliuk, A., Gámbaro, F., Tu, V.T., Keatts, L. and Mazet, J. (2021) A novel SARS-CoV-2 related coronavirus in bats from Cambodia. bioRxiv. [doi: 10.1101/2021.01.26.428212]

Knowledge of the origin and reservoir of the coronavirus responsible for the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is still fragmentary. To date, the closest relatives to SARS-CoV-2 have been detected in Rhinolophus bats sampled in the Yunnan province, China. Here we describe the identification of SARS-CoV-2 related coronaviruses in two Rhinolophus shameli bats sampled in Cambodia in 2010. Metagenomic sequencing identified nearly identical viruses sharing 92.6% nucleotide identity with SARS-CoV-2. Most genomic regions are closely related to SARS-CoV-2, with the exception of a small region corresponding to the spike N terminal domain. The discovery of these viruses in a bat species not found in China indicates that SARS-CoV-2 related viruses have a much wider geographic distribution than previously understood, and suggests that Southeast Asia represents a key area to consider in the ongoing search for the origins of SARS-CoV-2, and in future surveillance for coronaviruses.

Ge, X.-Y., Li, J.-L., Yang, X.-L., Chmura, A.A., Zhu, G., Epstein, J.H., Mazet, J.K., Hu, B., Zhang, W. and Peng, C. (2013) Isolation and characterization of a bat SARS-like coronavirus that uses the ACE2 receptor. Nature 503:535-538. [doi: 10.1038/nature12711]

The 2002–3 pandemic caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) was one of the most significant public health events in recent history1. An ongoing outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus2 suggests that this group of viruses remains a key threat and that their distribution is wider than previously recognized. Although bats have been suggested to be the natural reservoirs of both viruses3,4,5, attempts to isolate the progenitor virus of SARS-CoV from bats have been unsuccessful. Diverse SARS-like coronaviruses (SL-CoVs) have now been reported from bats in China, Europe and Africa5,6,7,8, but none is considered a direct progenitor of SARS-CoV because of their phylogenetic disparity from this virus and the inability of their spike proteins to use the SARS-CoV cellular receptor molecule, the human angiotensin converting enzyme II (ACE2)9,10. Here we report whole-genome sequences of two novel bat coronaviruses from Chinese horseshoe bats (family: Rhinolophidae) in Yunnan, China: RsSHC014 and Rs3367. These viruses are far more closely related to SARS-CoV than any previously identified bat coronaviruses, particularly in the receptor binding domain of the spike protein. Most importantly, we report the first recorded isolation of a live SL-CoV (bat SL-CoV-WIV1) from bat faecal samples in Vero E6 cells, which has typical coronavirus morphology, 99.9% sequence identity to Rs3367 and uses ACE2 from humans, civets and Chinese horseshoe bats for cell entry. Preliminary in vitro testing indicates that WIV1 also has a broad species tropism. Our results provide the strongest evidence to date that Chinese horseshoe bats are natural reservoirs of SARS-CoV, and that intermediate hosts may not be necessary for direct human infection by some bat SL-CoVs. They also highlight the importance of pathogen-discovery programs targeting high-risk wildlife groups in emerging disease hotspots as a strategy for pandemic preparedness.

Ge, X.-Y., Wang, N., Zhang, W., Hu, B., Li, B., Zhang, Y.-Z., Zhou, J.-H., Luo, C.-M., Yang, X.-L. and Wu, L.-J. (2016) Coexistence of multiple coronaviruses in several bat colonies in an abandoned mineshaft. Virologica Sinica 31:31-40. [doi: 10.1007/s12250-016-3713-9]

Since the 2002–2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak prompted a search for the natural reservoir of the SARS coronavirus, numerous alpha- and betacoronaviruses have been discovered in bats around the world. Bats are likely the natural reservoir of alpha- and beta-coronaviruses, and due to the rich diversity and global distribution of bats, the number of bat coronaviruses will likely increase. We conducted a surveillance of coronaviruses in bats in an abandoned mineshaft in Mojiang County, Yunnan Province, China, from 2012–2013. Six bat species were frequently detected in the cave: Rhinolophus sinicus, Rhinolophus affinis, Hipposideros pomona, Miniopterus schreibersii, Miniopterus fuliginosus, and Miniopterus fuscus. By sequencing PCR products of the coronavirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase gene (RdRp), we found a high frequency of infection by a diverse group of coronaviruses in different bat species in the mineshaft. Sequenced partial RdRp fragments had 80%–99% nucleic acid sequence identity with well-characterized Alphacoronavirus species, including BtCoV HKU2, BtCoV HKU8, and BtCoV1,and unassigned species BtCoV HKU7 and BtCoV HKU10. Additionally, the surveillance identified two unclassified betacoronaviruses, one new strain of SARS-like coronavirus, and one potentially new betacoronavirus species. Furthermore, coronavirus co-infection was detected in all six batspecies, a phenomenon that fosters recombination and promotes the emergence of novel virus strains. Our findings highlight the importance of bats as natural reservoirs of coronaviruses and the potentially zoonotic source of viral pathogens.

Guo, H., Hu, B., Si, H.-r., Zhu, Y., Zhang, W., Li, B., Li, A., Geng, R., Lin, H.-F. and Yang, X.-L. (2021) Identification of a novel lineage bat SARS-related coronaviruses that use bat ACE2 receptor. bioRxiv. [doi: 10.1101/2021.05.21.445091]

Severe respiratory disease coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) causes the most devastating disease, COVID-19, of the recent century. One of the unsolved scientific questions around SARS-CoV-2 is the animal origin of this virus. Bats and pangolins are recognized as the most probable reservoir hosts that harbor the highly similar SARS-CoV-2 related viruses (SARSr-CoV-2). Here, we report the identification of a novel lineage of SARSr-CoVs, including RaTG15 and seven other viruses, from bats at the same location where we found RaTG13 in 2015. Although RaTG15 and the related viruses share 97.2% amino acid sequence identities to SARS-CoV-2 in the conserved ORF1b region, but only show less than 77.6% to all known SARSr-CoVs in genome level, thus forms a distinct lineage in the Sarbecovirus phylogenetic tree. We then found that RaTG15 receptor binding domain (RBD) can bind to and use Rhinolophus affinis bat ACE2 (RaACE2) but not human ACE2 as entry receptor, although which contains a short deletion and has different key residues responsible for ACE2 binding. In addition, we show that none of the known viruses in bat SARSr-CoV-2 lineage or the novel lineage discovered so far use human ACE2 efficiently compared to SARSr-CoV-2 from pangolin or some of the SARSr-CoV-1 lineage viruses. Collectively, we suggest more systematic and longitudinal work in bats to prevent future spillover events caused by SARSr-CoVs or to better understand the origin of SARS-CoV-2.

MacLean, O.A., Lytras, S., Weaver, S., Singer, J.B., Boni, M.F., Lemey, P., Pond, S.L.K. and Robertson, D.L. (2021) Natural selection in the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 in bats created a generalist virus and highly capable human pathogen. PLoS Biology 19:e3001115. [doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3001115]

Virus host shifts are generally associated with novel adaptations to exploit the cells of the new host species optimally. Surprisingly, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has apparently required little to no significant adaptation to humans since the start of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and to October 2020. Here we assess the types of natural selection taking place in Sarbecoviruses in horseshoe bats versus the early SARS-CoV-2 evolution in humans. While there is moderate evidence of diversifying positive selection in SARS-CoV-2 in humans, it is limited to the early phase of the pandemic, and purifying selection is much weaker in SARS-CoV-2 than in related bat Sarbecoviruses. In contrast, our analysis detects evidence for significant positive episodic diversifying selection acting at the base of the bat virus lineage SARS-CoV-2 emerged from, accompanied by an adaptive depletion in CpG composition presumed to be linked to the action of antiviral mechanisms in these ancestral bat hosts. The closest bat virus to SARS-CoV-2, RmYN02 (sharing an ancestor about 1976), is a recombinant with a structure that includes differential CpG content in Spike; clear evidence of coinfection and evolution in bats without involvement of other species. While an undiscovered “facilitating” intermediate species cannot be discounted, collectively, our results support the progenitor of SARS-CoV-2 being capable of efficient human–human transmission as a consequence of its adaptive evolutionary history in bats, not humans, which created a relatively generalist virus.

Wacharapluesadee, S., Tan, C.W., Maneeorn, P., Duengkae, P., Zhu, F., Joyjinda, Y., Kaewpom, T., Chia, W.N., Ampoot, W. and Lim, B.L. (2021) Evidence for SARS-CoV-2 related coronaviruses circulating in bats and pangolins in Southeast Asia. Nature communications 12:1-9. doi: [doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21240-1]

Among the many questions unanswered for the COVID-19 pandemic are the origin of SARS-CoV-2 and the potential role of intermediate animal host(s) in the early animal-to-human transmission. The discovery of RaTG13 bat coronavirus in China suggested a high probability of a bat origin. Here we report molecular and serological evidence of SARS-CoV-2 related coronaviruses (SC2r-CoVs) actively circulating in bats in Southeast Asia. Whole genome sequences were obtained from five independent bats (Rhinolophus acuminatus) in a Thai cave yielding a single isolate (named RacCS203) which is most related to the RmYN02 isolate found in Rhinolophus malayanus in Yunnan, China. SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies were also detected in bats of the same colony and in a pangolin at a wildlife checkpoint in Southern Thailand. Antisera raised against the receptor binding domain (RBD) of RmYN02 was able to cross-neutralize SARS-CoV-2 despite the fact that the RBD of RacCS203 or RmYN02 failed to bind ACE2. Although the origin of the virus remains unresolved, our study extended the geographic distribution of genetically diverse SC2r-CoVs from Japan and China to Thailand over a 4800-km range. Cross-border surveillance is urgently needed to find the immediate progenitor virus of SARS-CoV-2.

Zhou, P., Yang, X.-L., Wang, X.-G., Hu, B., Zhang, L., Zhang, W., Si, H.-R., Zhu, Y., Li, B. and Huang, C.-L. (2020) A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 579:270-273. [doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7]

Since the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) 18 years ago, a large number of SARS-related coronaviruses (SARSr-CoVs) have been discovered in their natural reservoir host, bats1,2,3,4. Previous studies have shown that some bat SARSr-CoVs have the potential to infect humans5,6,7. Here we report the identification and characterization of a new coronavirus (2019-nCoV), which caused an epidemic of acute respiratory syndrome in humans in Wuhan, China. The epidemic, which started on 12 December 2019, had caused 2,794 laboratory-confirmed infections including 80 deaths by 26 January 2020. Full-length genome sequences were obtained from five patients at an early stage of the outbreak. The sequences are almost identical and share 79.6% sequence identity to SARS-CoV. Furthermore, we show that 2019-nCoV is 96% identical at the whole-genome level to a bat coronavirus. Pairwise protein sequence analysis of seven conserved non-structural proteins domains show that this virus belongs to the species of SARSr-CoV. In addition, 2019-nCoV virus isolated from the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of a critically ill patient could be neutralized by sera from several patients. Notably, we confirmed that 2019-nCoV uses the same cell entry receptor—angiotensin converting enzyme II (ACE2)—as SARS-CoV.

Zhou, P. et al. (2020) Addendum: A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 588:E6-E6. [doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2951-z]

Zhou, H., Ji, J., Chen, X., Bi, Y., Li, J., Hu, T., Song, H., Chen, Y., Cui, M. and Zhang, Y. (2021) Identification of novel bat coronaviruses sheds light on the evolutionary origins of SARS-CoV-2 and related viruses. bioRxiv. doi: [doi: 10.1101/2021.03.08.434390]

Although a variety of SARS-CoV-2 related coronaviruses have been identified, the evolutionary origins of this virus remain elusive. We describe a meta-transcriptomic study of 411 samples collected from 23 bat species in a small (~1100 hectare) region in Yunnan province, China, from May 2019 to November 2020. We identified coronavirus contigs in 40 of 100 sequencing libraries, including seven representing SARS-CoV-2-like contigs. From these data we obtained 24 full-length coronavirus genomes, including four novel SARS-CoV-2 related and three SARS-CoV related genomes. Of these viruses, RpYN06 exhibited 94.5% sequence identity to SARS-CoV-2 across the whole genome and was the closest relative of SARS-CoV-2 in the ORF1ab, ORF7a, ORF8, N, and ORF10 genes. The other three SARS-CoV-2 related coronaviruses were nearly identical in sequence and clustered closely with a virus previously identified in pangolins from Guangxi, China, although with a genetically distinct spike gene sequence. We also identified 17 alphacoronavirus genomes, including those closely related to swine acute diarrhea syndrome virus and porcine epidemic diarrhea virus. Ecological modeling predicted the co-existence of up to 23 Rhinolophus bat species in Southeast Asia and southern China, with the largest contiguous hotspots extending from South Lao and Vietnam to southern China. Our study highlights both the remarkable diversity of bat viruses at the local scale and that relatives of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV circulate in wildlife species in a broad geographic region of Southeast Asia and southern China. These data will help guide surveillance efforts to determine the origins of SARS-CoV-2 and other pathogenic coronaviruses.

Thursday, December 31, 2020

On the importance of controls

When doing an exeriment, it's important to keep the number of variables to a minimum and it's important to have scientific controls. There are two types of controls. A negative control covers the possibility that you will get a signal by chance; for example, if you are testing an enzyme to see whether it degrades sugar then the negative control will be a tube with no enzyme. Some of the sugar may degrade spontaneoulsy and you need to know this. A positive control is when you deliberately add something that you know will give a positive result; for example, if you are doing a test to see if your sample contains protein then you want to add an extra sample that contains a known amount of protein to make sure all your reagents are working.

Lots of controls are more complicated than the examples I gave but the principle is important. It's true that some experiments don't appear to need the appropriate controls but that may be an illusion. The controls might still be necessary in order to properly interpret the results but they're not done because they are very difficult. This is often true of genomics experiments.

Tuesday, January 14, 2020

The Three Domain Hypothesis: RIP

The original idea was promoted by Carl Woese and his colleagues in the early 1980s. It was based on the discovery of archaebacteria as a distinct clade that was different from other bacteria (eubacteria). It also became clear that some eukaryotic genes (e.g. ribosomal RNA) were more closely related to archaebacterial genes and the original data indicated that eukaryotes formed another distinct group separate from either the archaebacteria or eubacteria. This gave rise to the Three Domain Hypothesis where each of the groups, bacteria (Eubacteria), archaebacteria (Archaea), and eukaryotes (Eucarya, Eukaryota), formed a separate clade that contained multiple kingdoms. These clades were called Domains.

Friday, November 09, 2018

Celebrating 50 years of Neutral Theory

The journal of Molecular Biology and Evolution has published a special issue: Celebrating 50 years of the Neutral Theory. The key paper published 50 years ago was Motoo Kimura's paper on “Evolutionary rate at the molecular level” (Kimura, 1968) followed shortly after by a paper from Jack Lester King and Thomas Jukes on "Non-Darwinian Evolution" (King and Jukes, 1969).

The special issue contains reprints of two classic papers published in Molecular Biology and Evolution in 1983 and 2005. In addition, there are 14 reviews and opinions written by editors of the journal and published earlier this year (see below). It's interesting that several of the editors of a leading molecular evolution journal are challenging the importance of Neutral Theory and one of them (senior editor Matthew Hahn) is downright hostile.

Friday, July 13, 2018

How many protein-coding genes in the human genome?

The three main human databases (GENCODE/Ensembl, RefSeq, UniProtKB) contain a total of 22,210 protein-coding genes but only 19,446 of these genes are found in all three databases. That leaves 2764 potential genes that may or may not be real. A recent publication suggests that most of them are not real genes (Abascal et al., 2018). The issue is the same problem that I discussed in recent posts [Disappearing genes: a paper is refuted before it is even published] [Nature falls (again) for gene hype].

Saturday, February 03, 2018

What's in Your Genome?: Chapter 5: Regulation and Control of Gene Expression

I'm working (slowly) on a book called What's in Your Genome?: 90% of your genome is junk! The first chapter is an introduction to genomes and DNA [What's in Your Genome? Chapter 1: Introducing Genomes ]. Chapter 2 is an overview of the human genome. It's a summary of known functional sequences and known junk DNA [What's in Your Genome? Chapter 2: The Big Picture]. Chapter 3 defines "genes" and describes protein-coding genes and alternative splicing [What's in Your Genome? Chapter 3: What Is a Gene?]. Chapter 4 is all about pervasive transcription and genes for functional noncoding RNAs [What's in Your Genome? Chapter 4: Pervasive Transcription].

Chapter 5 is Regulation and Control of Gene Expression.Chapter 5: Regulation and Control of Gene Expression

What do we know about regulatory sequences?

The fundamental principles of regulation were worked out in the 1960s and 1970s by studying bacteria and bacteriophage. The initiation of transcription is controlled by activators and repressors that bind to DNA near the 5′ end of a gene. These transcription factors recognize relatively short sequences of DNA (6-10 bp) and their interactions have been well-characterized. Transcriptional regulation in eukaryotes is more complicated for two reasons. First, there are usually more transcription factors and more binding sites per gene. Second, access to binding sites depends of the state of chromatin. Nucleosomes forming high order structures create a "closed" domain where DNA binding sites are not accessible. In "open" domains the DNA is more accessible and transcription factors can bind. The transition between open and closed domains is an important addition to regulating gene expression in eukaryotes.The limitations of genomics

By their very nature, genomics studies look at the big picture. Such studies can tell us a lot about how many transcription factors bind to DNA and how much of the genome is transcribed. They cannot tell you whether the data actually reflects function. For that, you have to take a more reductionist approach and dissect the roles of individual factors on individual genes. But working on single genes can be misleading ... you may miss the forest for the trees. Genomic studies have the opposite problem, they may see a forest where there are no trees.Regulation and evolution

Much of what we see in evolution, especially when it comes to phenotypic differences between species, is due to differences in the regulation of shared genes. The idea dates back to the 1930s and the mechanisms were worked out mostly in the 1980s. It's the reason why all complex animals should have roughly the same number of genes—a prediction that was confirmed by sequencing the human genome. This is the field known as evo-devo or evolutionary developmental biology.Box 5-1: Can complex evolution evolve by accident?

Open and closed chromatin domainsSlightly harmful mutations can become fixed in a small population. This may cause a gene to be transcribed less frequently. Subsequent mutations that restore transcription may involve the binding of an additional factor to enhance transcription initiation. The result is more complex regulation that wasn't directly selected.

Gene expression in eukaryotes is regulated, in part, by changing the structure of chromatin. Genes in domains where nucleosomes are densely packed into compact structures are essentially invisible. Genes in more open domains are easily transcribed. In some species, the shift between open and closed domains is associated with methylation of DNA and modifications of histones but it's not clear whether these associations cause the shift or are merely a consequence of the shift.Box 5-2: X-chromosome inactivation

Box 5-3: Regulating gene expression byIn females, one of the X-chromosomes is preferentially converted to a heterochromatic state where most of the genes are in closed domains. Consequently, many of the genes on the X chromosome are only expressed from one copy as is the case in males. The partial inactivation of an X-chromosome is mediated by a small regulatory RNA molecule and this inactivated state is passed on to all subsequent descendants of the original cell.

rearranging the genome

ENCODE does it againIn several cases, the regulation of gene expression is controlled by rearranging the genome to bring a gene under the control of a new promoter region. Such rearrangements also explain some developmental anomalies such as growth of legs on the head fruit flies instead of antennae. They also account for many cancers.

Genomic studies carried out by the ENCODE Consortium reported that a large percentage of the human genome is devoted to regulation. What the studies actually showed is that there are a large number of binding sites for transcription factors. ENCODE did not present good evidence that these sites were functional.Does regulation explain junk?

The presence of huge numbers of spurious DNA binding sites is perfectly consistent with the view that 90% of our genome is junk. The idea that a large percentage of our genome is devoted to transcriptional regulation is inconsistent with everything we know from the the studies of individual genes.Box 5-3: A thought experiment

Small RNAs—a revolutionary discovery?Ford Doolittle asks us to imagine the following thought experiment. Take the fugu genome, which is very much smaller than the human genome, and the lungfish genome, which is very much larger, and subject them to the same ENCODE analysis that was performed on the human genome. All three genomes have approximately the same number of genes and most of those genes are homologous. Will the number of transcription factor biding sites be similar in all three species or will the number correlate with the size of the genomes and the amount of junk DNA?

Does the human genome contain hundreds of thousands of gene for small non-coding RNAs that are required for the complex regulation of the protein-coding genes?A “theory” that just won’t die

"... we have refuted the specific claims that most of the observed transcription across the human genome is random and put forward the case over many years that the appearance of a vast layer of RNA-based epigenetic regulation was a necessary prerequisite to the emergence of developmentally and cognitively advanced organisms." (Mattick and Dinger, 2013)What the heck is epigenetics?

Epigenetics is a confusing term. It refers loosely to the regulation of gene expression by factors other than differences in the DNA. It's generally assumed to cover things like methylation of DNA and modification of histones. Both of these effects can be passed on from one cell to the next following mitosis. That fact has been known for decades. It is not controversial. The controversy is about whether the heritability of epigenetic features plays a significant role in evolution.Box 5-5: The Weismann barrier

How should science journalists cover this story?The Weisman barrier refers to the separation between somatic cells and the germ line in complex multicellular organisms. The "barrier" is the idea that changes (e.g. methylation, histone modification) that occur in somatic cells can be passed on to other somatic cells but in order to affect evolution those changes have to be transferred to the germ line. That's unlikely. It means that Lamarckian evolution is highly improbable in such species.

The question is whether a large part of the human genome is devoted to regulation thus accounting for an unexpectedly large genome. It's an explanation that attempts to refute the evidence for junk DNA. The issue is complex and very few science journalists are sufficiently informed enough to do it justice. They should, however, be making more of an effort to inform themselves about the controversial nature of the claims made by some scientists and they should be telling their readers that the issue has not yet been resolved.

Monday, June 26, 2017

Debating alternative splicing (Part III)

Opponents (I am one) argue that most splice variants are due to splicing errors and most of those predicted protein isoforms don't exist. (We also argue that the differences between humans and other animals can be adequately explained by differential regulation of 20,000 protein-coding genes.) The controversy can only be resolved when proponents of massive alternative splicing provide evidence to support their claim that there are 100,000 functional proteins.

Thursday, June 22, 2017

Are most transcription factor binding sites functional?

The ongoing debate over junk DNA often revolves around data collected by ENCODE and others. The idea that most of our genome is transcribed (pervasive transcription) seems to indicate that genes occupy most of the genome. The opposing view is that most of these transcripts are accidental products of spurious transcription. We see the same opposing views when it comes to transcription factor binding sites. ENCODE and their supporters have mapped millions of binding sites throughout the genome and they believe this represent abundant and exquisite regulation. The opposing view is that most of these binding sites are spurious and non-functional.

The messy view is supported by many studies on the biophysical properties of transcription factor binding. These studies show that any DNA binding protein has a low affinity for random sequence DNA. They will also bind with much higher affinity to sequences that resemble, but do not precisely match, the specific binding site [How RNA Polymerase Binds to DNA; DNA Binding Proteins]. If you take a species with a large genome, like us, then a typical DNA protein binding site of 6 bp will be present, by chance alone, at 800,000 sites. Not all of those sites will be bound by the transcription factor in vivo because some of the DNA will be tightly wrapped up in dense chromatin domains. Nevertheless, an appreciable percentage of the genome will be available for binding so that typical ENCODE assays detect thousand of binding sites for each transcription factor.This information appears in all the best textbooks and it used to be a standard part of undergraduate courses in molecular biology and biochemistry. As far as I can tell, the current generation of new biochemistry researchers wasn't taught this information.

Wednesday, June 21, 2017

John Mattick still claims that most lncRNAs are functional

Most of the human genome is transcribed at some time or another in some tissue or another. The phenomenon is now known as pervasive transcription. Scientists have known about it for almost half a century.

At first the phenomenon seemed really puzzling since it was known that coding regions accounted for less than 1% of the genome and genetic load arguments suggested that only a small percentage of the genome could be functional. It was also known that more than half the genome consists of repetitive sequences that we now know are bits and pieces of defective transposons. It seemed unlikely back then that transcripts of defective transposons could be functional.Part of the problem was solved with the discovery of RNA processing, especially splicing. It soon became apparent (by the early 1980s) that a typical protein coding gene was stretched out over 37,000 bp of which only 1300 bp were coding region. The rest was introns and intron sequences appeared to be mostly junk.

Tuesday, December 06, 2016

How many proteins in the human proteome?

Humans have about 25,000 genes. About 20,000 of these genes are protein-coding genes.1 That means, of course, that humans make at least 20,000 proteins. Not all of them are different since the number of protein-coding genes includes many duplicated genes and gene families. We would like to know how many different proteins there are in the human proteome.

The latest issue of Science contains an insert with a chart of the human proteome produced by The Human Protein Atlas. Publication was timed to correspond with release of a new version of the Cell Atlas at the American Society of Cell Biology meeting in San Francisco. The Cell Atlas maps the location of about 12,000 proteins in various tissues and organs. Mapping is done primarily by looking at whether or not a gene is transcribed in a given tissue.A total of 7367 genes (60%) are expressed in all tissues. These "housekeeping" genes correspond to the major metabolic pathways and the gene expression pathway (e.g. RNA polymerase subunits, ribosomal proteins, DNA replication proteins). Most of the remaining genes are tissue-specific or developmentally specific.

Tuesday, January 19, 2016

Massimo Pigliucci tries to defend accommodationism (again): result is predictable

I prefer the broad view of science as a way of knowing that relies on evidence, rational thinking, and healthy skepticism. This broad view of science is not universal—but it's not uncommon. In fact, Alan Sokel has defended this view of Massimo Pigiucci's own blog: [What is science and why should we care? — Part III]. According to this view, any attempt to gain knowledge should employ the scientific worldview. Historian and philosophers should follow this path if they hope to be successful. Pigliucci should know that there are different definitions and any discussion of the compatibility of science and religion must take these differences into account.

Monday, January 04, 2016

Answering two questions from Vincent Torley

Torley disagrees, obviously, but he focuses on a couple of the scientific statements in Jerry Coyne's post and comes up with Two quick questions for Professor Coyne.

I hope Professor Coyne won't mind if I answer.

Before answering, let's take note of the fact that Vincent Torley has been convinced by the evidence that most of our genome is junk. I wonder how that will go over in the ID community?

Here's question #1 ...