We may not know a lot about how artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms work but the one thing we do know is that they are only as good as their databases. If you ask an AI program to tell you when Charles Darwin was born then chances are good it's going to give you the correct answer because that information is in Wikipedia and lots of other reliable online sources.

However, if you ask it to tell you how many genes are in the human genome it will not give you the correct answer. The correct answer is that we don't know for sure because it depends on how you define a gene and how many non-coding genes there are using various definitions. That's not the answer you will get. (I personally believe that there are only about 1000 non-coding genes but I don't expect a good "intelligence" program to favor my view over others. I DO expect it to not favor other opinions over mine.)

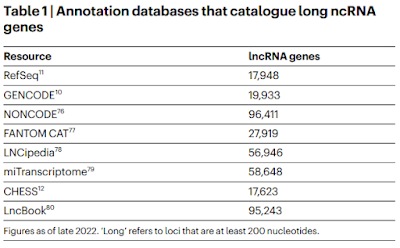

I just asked ChatGPT and it told me that there are tens of thousands of non-coding genes based on the Human Genome Project plus GENCODE and Ensemble annotations. This is correct ... and misleading. It's giving the best answer it can based on the databases it searches. However, many of us are skeptical of the GENCODE and Ensemble annotations and for good reason. They tend to err on the side of inclusion in order to avoid false negatives. In other words, they don't want to risk ignoring a real biologically relevant feature for lack of evidence so they deliberately risk including a lot of false positives. This is why those databases include a lot of questionable features such as non-coding genes, multiple transcription start sites, multiple splice variants, and tons of potential regulatory elements.

Along comes AlphaGenome. It's an AI program designed to scan those GENCODE and Ensemble databases to identify important features that might play a role in genetic diseases. What could possibly go wrong? [How intelligent is artificial intelligence?] [Will AlphaGenome from Google DeepMind help us understand the human genome?]

The average science writer jumped all over the original announcement of AlphGenome to let us all know that artificial intelligence was going to solve the problem of the mysterious genome. Apparently the complexity of the human genome has astonished scientists ever since the first human genome sequence was published 25 years ago.1 The typical article on AlphaGenome fits nicely into the common theme that AI is soon going to rule the world.

That's why I was excited to pick up my copy of the New York Times yesterday and see that Carl Zimmer had written about AlphaGenome. Finally, an intelligent, highly respected, science writer was going to give us the truth. Here's the article that I saw in my version of the paper. (It was originally published several weeks ago on January 28, 2026.)

What a disappointment! Zimmer goes with the hype about AlphaGenome and repeats some of the tropes that he has avoided in the past. For example, he writes about how alternative splicing can create hundreds of different proteins from a single gene and how regulatory sequences can lie thousands or million of base pairs away from a gene. (There's no question that this is true for a small number of transcription factor binding sites but the vast majority are close to the promoter.)

Zimmer gives an example showing that AlphaGenome identified a regulatory sequence for a gene called TAL1, implying that the program will help decipher the rest of the genome. The general tone of the newspaper article is that AlphaGenome will be of great help to scientists who want to understand the human genome.I checked the online version of Carl Zimmer's article in order to prepare for this blog post. I was surprised to see that there were lots of things in the online version that weren't in the newspaper article. For example, Zimmer quotes my colleague Alex Palazzo saying that everybody uses AlphaFold to study proteins then later on in the article Zimmer notes that, "But the more scientists studied the human genome, the more complicated and messy it turned out to be." The newspaper article left out the words "and messy" and that's significant because junk DNA supporters like Alex Palazzo often refer to the human genome as "messy" and full of junk DNA and that's a very different perspective than opponents of junk DNA who emphasize things like "complicated" and "mysterious."2

Zimmer has an even more revealing section that's in the online version but not the newspaper version.

Peter Koo, a computational biologist at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York who was not involved in the project, said that AlphaGenome represented an important step forward in applying artificial intelligence to the genome. “It’s an engineering marvel,” he said.

But Dr. Koo and other outside experts cautioned that it represented just one step on a long road ahead. “This is not AlphaFold, and it’s not going to win the Nobel Prize,” said Mark Gerstein, a computational biologist at Yale.

AlphaGenome will be useful. Dr. Gerstein said that he would probably add it to his toolbox for exploring DNA, and others expect to follow suit. But not all scientists trust A.I. programs like AlphaGenome to help them understand the genome.

“I see no value in them at all right now,” said Steven Salzberg, a computational biologist at Johns Hopkins University. “I think there are a lot of smart people wasting their time.”

The end of the online article is quite different from the final paragraphs of the newspaper article. In the newspaper article, Zimmer describes the TAL1 result then ends it with the paragraph starting with "In reality." I've highlighted that paragraph in the quotations below from the online version.

The AlphaGenome researchers shared their TAL1 predictions with Dr. Marc Mansour, a hematologist at University College London who spent years uncovering the leukemia-driving mutations with lab experiments.

“It was quite mind-blowing,” Dr. Mansour said. “It really showed how powerful this is.”

But, Dr. Mansour noted, AlphaGenome’s predictive powers fade the farther its gaze strays from a particular gene. He is now using AlphaGenome in his cancer research but does not blindly accept its results.

“These prediction tools are still prediction tools,” he said. “We still need to go to the lab.”

Dr. Salzberg of Johns Hopkins is less sanguine about AlphaGenome, in part because he thinks its creators put too much trust in the data they trained it on. Scientists who study splice sites don’t agree on which sites are real and which are genetic mirages. As a result, they have created databases that contain different catalogs of splice sites.

“The community has been working for 25 years to try to figure out what are all the splice sites in the human genome, and we’re still not really there,” Dr. Salzberg said. “We don’t have an agreed-upon gold-standard set.”

Dr. Pollard also cautioned that AlphaGenome was a long way from being a tool that doctors could use to scan the genomes of patients for threats to their health. It predicts only the effects of a single mutation on one standard human genome.

In reality, any two people have millions of genetic differences in their DNA. Assessing the effects of all those variations throughout a patient’s body remains far beyond AlphaGenome’s industrial-strength power.

“It is a much, much harder problem — and yet that’s the problem we need to solve if we want to use a model like this for health care,” Dr. Pollard said.

The net effect of these differences is to transform the article from one that promotes AlphaGenome in the newspaper version to one that's far more skeptical in the online version. I believe that the online version is far more accurate and reflects the high standard that I expect from Carl Zimmer. I'm assuming that the newspaper article was edited for the New York Times supplement that I read and I'm assuming that Zimmer did not approve of that edit.

Note: The cartoon was generated by ChatGPT in response to the request, "draw a cartoon illustrating GIGO - garbage in garbage out."

Note: The photo is from 10 years ago when Carl was in Toronto working on his junk DNA article for The New York Times [Is Most of Our DNA Garbage?]. That's Alex Palazzo on the left, then me, Ryan Gregory, and Carl Zimmer on the right.

1. Most knowledgeable scientists were not astonished to learn that 90% of our genome really is junk and there are fewer than 30,000 genes.

2. See the last chapter of my book: "Chapter 11: Zen and the Art of Coping with a Sloppy Genome."