More Recent Comments

Saturday, October 05, 2013

Barry Arrington, Junk DNA, and Why We Call Them Idiots

I'm reminded of the word "pathos" but I had to look it up to make sure I got it right. It means something that causes people to feel pity, sadness, or even compassion. It's the right word to describe what's happening. It's also similar to the word "pathetic."

Here's what's happening.

As you know, Barry Arrington claimed that the IDiots made a prediction. They predicted that there's no such thing as junk DNA. They predicted that most of our genome would turn out to have a function [Let’s Put This One To Rest Please]. That's much is true. It makes perfect sense because an Intelligent Design Creator wouldn't create a genome that was 90% junk.

Tuesday, May 24, 2011

Junk & Jonathan: Part 6—Chapter 3

This is part 6 of my review of The Myth of Junk DNA. For a list of other postings on this topic see the link to Genomes & Junk DNA in the "theme box" below or in the sidebar under "Themes."

This is part 6 of my review of The Myth of Junk DNA. For a list of other postings on this topic see the link to Genomes & Junk DNA in the "theme box" below or in the sidebar under "Themes."We learn in Chapter 9 that Wells has two categories of evidence against junk DNA. The first covers evidence that sequences probably have a function and the second covers specific known examples of functional sequences. In the first category there are two lines of evidence: transcription and conservation. Both of them are covered in Chapter 3 making this one of the most important chapters in the book. The remaining category of specific examples is described in Chapters 4-7.

The title of Chapter 3 is Most DNA Is Transcribed into RNA. As you might have anticipated, the focus of Wells' discussion is the ENCODE pilot project that detected abundant transcription in the 1% of the genome that they analyzed (ENCODE Project Consortium, 2007). Their results suggest that most of the genome is transcribed. Other studies support this idea and show that transcripts often overlap and many of them come from the opposite strand in a gene giving rise to antisense RNAs.

The original Nature paper says,

... our studies provide convincing evidence that the genome is pervasively transcribed, such that the majority of its bases can be found in primary transcripts, including non-protein-coding transcripts, and those that extensively overlap one another.The authors of these studies firmly believe that evidence of transcription is evidence of function. This has even led some of them to propose a new definition of a gene [see What is a gene, post-ENCODE?]. There's no doubt that many molecular biologists take this data to mean that most of our genome has a function and that's the same point that Wells makes in his book. It's evidence against junk DNA.

What are these transcripts doing? Wells devotes a section to "Specific Functions of Non-Protein-Coding RNAs." These RNAs may be news to most readers but they are well known to biochemists and molecular biologists. This is not the place to describe all the known functional non-coding RNAs but keep in mind that there are three main categories: ribosomal RNA (rRNA), transfer RNA (tRNA), and a heterogeneous category called small RNAs. There are dozens of different kinds of small RNAs including unique ones such as the 7SL RNA of signal recognition factor, the P1 RNA of RNAse P and the guide RNA in telomerase. Other categories include the spliceosome RNAs, snoRNAs, piRNAs, siRNAs, and miRNAs. These RNAs have been studied for decades. It's important to note that the confirmed examples are transcribed from genes that make up less than 1% of the genome.

One interesting category is called "long noncoding RNAs" or lncRNAs. As the name implies, these RNAs are longer that the typical small RNAs. Their functions, if any, are largely unknown although a few have been characterized. If we add up all the genes for these RNAs and assume they are functional it will account for about 0.1% of the genome so this isn't an important category in the discussion about junk DNA.

Theme

Genomes

& Junk DNASo, we're left with a puzzle. If more than 90% of the genome is transcribed but we only know about a small number of functional RNAs then what about the rest?

Opponents of junk DNA—both creationists and scientists—would have you believe that there's a lot we don't know about genomes and RNA. They believe that we will eventually find functions for all this RNA and prove that the DNA that produces them isn't junk. This is a genuine scientific controversy. What do their scientific opponents (I am one) say about the ENCODE result?

Criticisms of the ENCODE analysis take two forms ...

- The data is wrong and only a small fraction of the genome is transcribed

- The data is mostly correct but the transcription is spurious and accidental. Most of the products are junk RNA.

Several papers have appeared that call into question the techniques used by the ENCODE consortium. They claim that many of the identified transcribed regions are artifacts. This is especially true of the repetitive regions of the genome that make up more than half of the total content. If any one of these regions is transcribed then the transcript will likely hybridize to the remaining repeats giving a false impression of the amount of DNA that is actually transcribed.

Of course, Wells doesn't mention any of these criticisms in Chapter 3. In fact, he implies that every published paper is completely accurate in spite of the fact that most of them have never been replicated and many have been challenged by subsequent work. The readers of The Myth of Junk DNA will assume, intentionally or otherwise, that if a paper appears in the scientific literature it must be true.

But criticism of the ENCODE results are so widespread that they can't be ignored so Wells is forced to deal with them in Chapter 8. (Why not in Chapter 3 when they are first mentioned?) In particular, Wells has to address the van Bakel et al. (2010) paper from Tim Hughes' lab here in Toronto. This paper was widely discussed when it came out last year [see: Junk RNA or Imaginary RNA?]. We'll deal with it when I cover Chapter 9 but, suffice to say, Wells dismisses the criticism.

Criticisms of the Interpretation

The other form of criticism focuses on the interpretation of the data rather than its accuracy. Most of us who teach transcription take pains to point out to our students that RNA polymerase binds non-specifically to DNA and that much of this binding will result in spurious transcription at a very low frequency. This is exactly what we expect from a knowledge of transcription initiation [How RNA Polymerase Binds to DNA]. The ENCODE data shows that most of the genome is "transcribed" at a frequency of once every few generations (or days) and this is exactly what we expect from spurious transcription. The RNAs are non-functional accidents due to the sloppiness of the process [Useful RNAs?].

Wells doesn't mention any of this. I don't know if that's because he's ignorant of the basic biochemistry and hasn't read the papers or whether he is deliberately trying to mislead his readers. It's probably a bit of both.

It's not as if this is some secret known only to the experts. The possibility of spurious transcription has come up frequently in the scientific literature in the past few years. For example, Guttmann et al. (2009) write,

Genomic projects over the past decade have used shotgun sequencing and microarray hybridization to obtain evidence for many thousands of additional non-coding transcripts in mammals. Although the number of transcripts has grown, so too have the doubts as to whether most are biologically functional. The main concern was raised by the observation that most of the intergenic transcripts show little to no evolutionary conservation. Strictly speaking, the absence of evolutionary conservation cannot prove the absence of function. But the remarkably low rate of conservation seen in the current catalogues of large non-coding transcripts (less than 5% of cases) is unprecedented and would require that each mammalian clade evolves its own distinct repertoire of non-coding transcripts. Instead, the data suggest that the current catalogues may consist largely of transcriptional noise, with a minority of bona fide functional lincRNAs hidden amid this background.This paper is in the Wells reference list so we know that he has read it.

What these authors are saying is that the data is consistent with spurious transcription (noise). Part of the evidence is the lack of any sequence conservation among the transcripts. It's as though they were mostly derived from junk DNA.

Sequence Conservation

Recall that the purpose of Chapter 3 is to show that junk DNA is probably functional. The first part of the chapter reportedly shows that most of our genome is transcribed. The second part addresses sequence conservation.

Here's what Wells says about sequence conservation.

Widespread transcription of non-protein-coding DNA suggests that the RNAs produced from such DNA might serve biological functions. Ironically, the suggestion that much non-protein-coding DNA might be functional also comes from evolutionary theory. If two lineages diverge from a common ancestor that possesses regions of non-protein-coding DNA, and these regions are really nonfunctional, then they will accumulate random mutations that are not weeded out by natural selection. Many generations later, the sequences of the corresponding non-protein-coding regions in the two descendant lineages will probably be very different. [Due to fixation by random genetic drift—LAM] On the other hand, if the original non-protein-coding DNA was functional, then natural selection will tend to weed out mutations affecting that function. Many generations later, the sequences of the corresponding non-protein-coding regions in the two descendant lineages will still be similar. (In evolutionary terminology, the sequences will be "conserved.") Turning the logic around, Darwinian theory implies that if evolutionarily divergent organisms share similar non-protein-coding DNA sequences, those sequences are probably functional.Wells then references a few papers that have detected such conserved sequences, including the Guttmann et al. (2009) paper mentioned above. They found "over a thousand highly conserved large non-coding RNAs in mammals." Indeed they did, and this is strong evidence of function.1 Every biochemist and molecular biologist will agree. One thousand lncRNAs represent 0.08% of the genome. The sum total of all other conserved sequences is also less than 1%. Wells forgets to mention this in his book. He also forgets to mention the other point that Guttman et al. make; namely, that the lack of sequence conservation suggests that the vast majority of transcripts are non-functional. (Oops!)

There's irony here. We know that the sequences of junk DNA are not conserved and this is taken as evidence (not conclusive) that the DNA is non-functional. The genetic load argument makes the same point. We know that the vast majority of spurious RNA transcripts are also not conserved from species to species and this strongly suggests that those RNAs are not functional. Wells ignores this point entirely—it never comes up anywhere in his book. On the other hand, when a small percentage of DNA (and transcripts) are conserved, this gets prominent mention.

Wells doesn't believe in common ancestry so he doesn't believe that sequences are "conserved." (Presumably they reflect common design or something like that.) Nevertheless, when an evolutionary argument of conservation suits his purpose he's happy to invoke it, while, at the same time, ignoring the far more important argument about lack of conservation of the vast majority of spurious transcripts. Isn't that strange behavior?

The bottom line hear is that Jonathan Wells is correct to point to the ENCODE data as a problem for junk DNA proponents. This is part of the ongoing scientific controversy over the amount of junk in our genome. Where I fault Wells is his failure to explain to his readers that this is disputed data and interpretation. There's no slam-dunk case for function here. In fact, the tide seems to turning more and more against the original interpretation of the data. Most knowledgeable biochemists and molecular biologists do not believe that >90% of our genome is transcribed to produce functional RNAs.

UPDATE: How much of the genome do we expect to be transcribed on a regular basis? Protein-encoding genes account for about 30% of the genome, including introns (mostly junk). They will be transcribed. Other genes produce functional RNAs and together they cover about 3% of the genome. Thus, we expect that roughly a third of the genome will be transcribed at some time during development. We also expect that a lot more of the genome will be transcribed on rare occasions just because of spurious (accidental) transcription initiation. This doesn't count. Some pseudogenes, defective transposons, and endogenous retroviruses have retained the ability to be transcribed on a regular basis. This may account for another 1-2% of the genome. They produce junk RNA.

1. Conservation is not proof of function. In an effort to test this hypothesis Nöbrega et al. (2004) deleted two large regions of the mouse genome containing large numbers of sequences corresponding to conserved non-coding RNAs. They found that the mice with the deleted regions showed no phenotypic effects indicating that the DNA was junk. Jonathan Wells forgot to mention this experiment in his book.

Guttman, M. et al. (2009) Chromatin signature reveals over a thousand highly conserved non-coding RNAs in mammals. Nature 458:223-227. [NIH Public Access]

Nörega, M.A., Zhu, Y., Plajzer-Frick, I., Afzal, V. and Rubin, E.M. (2004) Megabase deletions of gene deserts result in viable mice. Nature 431:988-993. [Nature]

The ENCODE Project Consortium (2007) Nature 447:799-816. [PDF]

Saturday, January 06, 2024

Why do Intelligent Design Creationists lie about junk DNA?

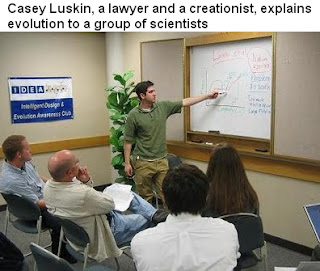

A recent post on Evolution News (sic) promotes a a new podcast: Casey Luskin on Junk DNA’s “Kuhnian Paradigm Shift”. You can listen to the podcast here but most Sandwalk readers won't bother because they've heard it all before. [see Paradigm shifting.]

Luskin repeats the now familiar refrain of claiming that scientists used to think that all non-coding DNA was junk. Then he goes on to list recent discoveries showing that some of this non-coding DNA is functional. The truth is that no knowledgeable scientist ever claimed that all non-coding DNA was junk. The original idea of junk DNA was based on evidence that only 10% of the genome is functional and these scientists knew that coding regions occupied only a few percent. Thus, right from the beginning, the experts on genome evolution knew about all sorts of functional non-coding DNA such as regulatory sequences, non-coding genes, and other things.

Friday, March 27, 2015

Plant biologists are confused about the meanings of junk DNA and genes

This is not a big deal and the authors of the paper don't even mention junk DNA.

The paper was reviewed by Peter M. Waterhouse and Roger P. Hellens in the same issue (Waterhouse and Hellens, 2015). They think it's a big deal. Here's what they say,

Friday, November 20, 2015

The truth about ENCODE

In September 2012, a batch of more than 30 articles presenting the results of the ENCODE (Encyclopaedia of DNA Elements) project was released. Many of these articles appeared in Nature and Science, the two most prestigious interdisciplinary scientific journals. Since that time, hundreds of other articles dedicated to the further analyses of the Encode data have been published. The time of hundreds of scientists and hundreds of millions of dollars were not invested in vain since this project had led to an apparent paradigm shift: contrary to the classical view, 80% of the human genome is not junk DNA, but is functional. This hypothesis has been criticized by evolutionary biologists, sometimes eagerly, and detailed refutations have been published in specialized journals with impact factors far below those that published the main contribution of the Encode project to our understanding of genome architecture. In 2014, the Encode consortium released a new batch of articles that neither suggested that 80% of the genome is functional nor commented on the disappearance of their 2012 scientific breakthrough. Unfortunately, by that time many biologists had accepted the idea that 80% of the genome is functional, or at least, that this idea is a valid alternative to the long held evolutionary genetic view that it is not. In order to understand the dynamics of the genome, it is necessary to re-examine the basics of evolutionary genetics because, not only are they well established, they also will allow us to avoid the pitfall of a panglossian interpretation of Encode. Actually, the architecture of the genome and its dynamics are the product of trade-offs between various evolutionary forces, and many structural features are not related to functional properties. In other words, evolution does not produce the best of all worlds, not even the best of all possible worlds, but only one possible world.How did we get to this stage where the most publicized result of papers published by leading scientists in the best journals turns out to be wrong, but hardly anyone knows it?

Back in September 2012, the ENCODE Consortium was preparing to publish dozens of papers on their analysis of the human genome. Most of the results were quite boring but that doesn't mean they were useless. The leaders of the Consortium must have been worried that science journalists would not give them the publicity they craved so they came up with a strategy and a publicity campaign to promote their work.

Their leader was Ewan Birney, a scientist with valuable skills as a herder of cats but little experience in evolutionary biology and the history of the junk DNA debate.

The ENCODE Consortium decided to add up all the transcription factor binding sites—spurious or not—and all the chromatin makers—whether or not they meant anything—and all the transcripts—even if they were junk. With a little judicious juggling of numbers they came up with the following summary of their results (Birney et al., 2012) ..

The human genome encodes the blueprint of life, but the function of the vast majority of its nearly three billion bases is unknown. The Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) project has systematically mapped regions of transcription, transcription factor association, chromatin structure and histone modification. These data enabled us to assign biochemical functions for 80% of the genome, in particular outside of the well-studied protein-coding regions. Many discovered candidate regulatory elements are physically associated with one another and with expressed genes, providing new insights into the mechanisms of gene regulation. The newly identified elements also show a statistical correspondence to sequence variants linked to human disease, and can thereby guide interpretation of this variation. Overall, the project provides new insights into the organization and regulation of our genes and genome, and is an expansive resource of functional annotations for biomedical research.See What did the ENCODE Consortium say in 2012? for more details on what the ENCODE Consortium leaders said, and did, when their papers came out.

The bottom line is that these leaders knew exactly what they were doing and why. By saying they have assigned biochemical functions for 80% of the genome they knew that this would be the headline. They knew that journalists and publicists would interpret this to mean the end of junk DNA. Most of ENCODE leaders actually believed it.

That's exactly what happened ... aided and abetted by the ENCODE Consortium, the journals Nature and Science, and gullible science journalists all over the world. (Ryan Gregory has published a list of articles that appeared in the popular press: The ENCODE media hype machine..)

Almost immediately the knowledgeable scientists and science writers tried to expose this publicity campaign hype. The first criticisms appeared on various science blogs and this was followed by a series of papers in the published scientific literature. Ed Yong, an experienced science journalist, interviewed Ewan Birney and blogged about ENCODE on the first day. Yong reported the standard publicity hype that most of our genome is functional and this interpretation is confirmed by Ewan Birney and other senior scientists. Two days later, Ed Yong started adding updates to his blog posting after reading the blogs of many scientists including some who were well-recognized experts on genomes and evolution [ENCODE: the rough guide to the human genome].

Within a few days of publishing their results the ENCODE Consortium was coming under intense criticism from all sides. A few journalists, like John Timmer, recongized right away what the problem was ...

Yet the third sentence of the lead ENCODE paper contains an eye-catching figure that ended up being reported widely: "These data enabled us to assign biochemical functions for 80 percent of the genome." Unfortunately, the significance of that statement hinged on a much less widely reported item: the definition of "biochemical function" used by the authors.Nature may have begun to realize that it made a mistake in promoting the idea that most of our genome was functional. Two days after the papers appeared, Brendan Maher, a Feature Editor for Nature, tried to get the journal off the hook but only succeeded in making matters worse [see Brendan Maher Writes About the ENCODE/Junk DNA Publicity Fiasco].

This was more than a matter of semantics. Many press reports that resulted painted an entirely fictitious history of biology's past, along with a misleading picture of its present. As a result, the public that relied on those press reports now has a completely mistaken view of our current state of knowledge (this happens to be the exact opposite of what journalism is intended to accomplish). But you can't entirely blame the press in this case. They were egged on by the journals and university press offices that promoted the work—and, in some cases, the scientists themselves.

[Most of what you read was wrong: how press releases rewrote scientific history]

Meanwhile, two private for-profit companies, illumina and Nature, team up to promote the ENCODE results. They even hire Tim Minchin to narrate it. This is what hype looks like ...

Soon articles began to appear in the scientific literature challenging the ENCODE Consortium's interpretation of function and explaining the difference between an effect—such as the binding of a transcription factor to a random piece of DNA—and a true biological function.

Eddy, S.R. (2012) The C-value paradox, junk DNA and ENCODE. Current Biology, 22:R898. [doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.10.002]

Niu, D. K., and Jiang, L. (2012) Can ENCODE tell us how much junk DNA we carry in our genome?. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 430:1340-1343. [doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.12.074]

Doolittle, W.F. (2013) Is junk DNA bunk? A critique of ENCODE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. (USA) published online March 11, 2013. [PubMed] [doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221376110]

Graur, D., Zheng, Y., Price, N., Azevedo, R. B., Zufall, R. A., and Elhaik, E. (2013) On the immortality of television sets: "function" in the human genome according to the evolution-free gospel of ENCODE. Genome Biology and Evolution published online: February 20, 2013 [doi: 10.1093/gbe/evt028

Eddy, S.R. (2013) The ENCODE project: missteps overshadowing a success. Current Biology, 23:R259-R261. [10.1016/j.cub.2013.03.023]

Hurst, L.D. (2013) Open questions: A logic (or lack thereof) of genome organization. BMC biology, 11:58. [doi:10.1186/1741-7007-11-58]

Morange, M. (2014) Genome as a Multipurpose Structure Built by Evolution. Perspectives in biology and medicine, 57:162-171. [doi: 10.1353/pbm.2014.000]

Palazzo, A.F., and Gregory, T.R. (2014) The Case for Junk DNA. PLoS Genetics, 10:e1004351. [doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004351]

By March 2013—six months after publication of the ENCODE papers—some editors at Nature decided that they had better say something else [see Anonymous Nature Editors Respond to ENCODE Criticism]. Here's the closest thing to an apology that they have ever written ....

The debate over ENCODE’s definition of function retreads some old battles, dating back perhaps to geneticist Susumu Ohno’s coinage of the term junk DNA in the 1970s. The phrase has had a polarizing effect on the life-sciences community ever since, despite several revisions of its meaning. Indeed, many news reports and press releases describing ENCODE’s work claimed that by showing that most of the genome was ‘functional’, the project had killed the concept of junk DNA. This claim annoyed both those who thought it a premature obituary and those who considered it old news.Oops! The importance of junk DNA is still an "important, open and debatable question" in spite of what the video sponsored by Nature might imply.

There is a valuable and genuine debate here. To define what, if anything, the billions of non-protein-coding base pairs in the human genome do, and how they affect cellular and system-level processes, remains an important, open and debatable question. Ironically, it is a question that the language of the current debate may detract from. As Ewan Birney, co-director of the ENCODE project, noted on his blog: “Hindsight is a cruel and wonderful thing, and probably we could have achieved the same thing without generating this unneeded, confusing discussion on what we meant and how we said it”.

(To this day, neither Nature nor Science have actually apologized for misleading the public about the ENCODE results. [see Science still doesn't get it ])

The ENCODE Consortium leaders responded in April 2014—eighteen months after their original papers were published.

Kellis, M., Wold, B., Snyder, M.P., Bernstein, B.E., Kundaje, A., Marinov, G.K., Ward, L.D., Birney, E., Crawford, G. E., and Dekker, J. (2014) Defining functional DNA elements in the human genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. (USA) 111:6131-6138. [doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318948111]

In that paper they acknowledge that there are multiple meanings of the word function and their choice of "biochemical" function may not have been the best choice ....

However, biochemical signatures are often a consequence of function, rather than causal. They are also not always deterministic evidence of function, but can occur stochastically.This is exactly what many scientists have been telling them. Apparently they did not know this in September 2012.

They also include in their paper a section on "Case for Abundant Junk DNA." It summarizes the evidence for junk DNA, evidence that the ENCODE Consortium did not acknowledge in 2012 and certainly didn't refute.

In answer to the question, "What Fraction of the Human Genome Is Functional?" they now conclude that ENCODE hasn't answered that question and more work is needed. They now claim that the real value of ENCODE is to provide "high-resolution, highly-reproducible maps of DNA segments with biochemical signatures associate with diverse molecular functions."

We believe that this public resource is far more important than any interim estimate of the fraction of the human genome that is functional.There you have it, straight from the horse's mouth. The ENCODE Consortium now believes that you should NOT interpret their results to mean that 80% of the genome is functional and therefore not junk DNA. There is good evidence for abundant junk DNA and the issue is still debatable.

I hope everyone pays attention and stops referring to the promotional hype saying that ENCODE has refuted junk DNA. That's not what the ENCODE Consortium leaders now say about their results.

Casane, D., Fumey, J., et Laurenti, P. (2015) L’apophénie d’ENCODE ou Pangloss examine le génome humain. Med. Sci. (Paris) 31: 680-686. [doi: 10.1051/medsci/20153106023]

Friday, May 23, 2008

Fugu, Pharyngula, and Junk

PZ Myers writes about Random Acts of Evolution in the latest issue of Seed magazine. The subtitle says it all.

PZ Myers writes about Random Acts of Evolution in the latest issue of Seed magazine. The subtitle says it all.The idea of humankind as a paragon of design is called into question by the puffer fish genome—the smallest, tidiest vertebrate genome of all.The genome of the puffer fish (Takifugu rubripes or Fugu rubripes) has about the same number of genes as other vertebrates (20,000) but its genome is only 400 Mb in size [Fugu Genome Project]. This is about 12.5% of the size of mammalian genomes.

THEME

Genomes & Junk DNA

Total Junk so far

53%

The Fugu Genome Project was initiated by workers who wanted to sequence a vertebrate genome with as little junk DNA as possible in order to determine which sequences are essential in vertebrate genomes. The small size of the fugu genome suggests that more than 80% of our genome is non-essential junk.

Many of you might recall the results of my Junk DNA Poll from last January. In case you've forgotten the results, I'll post them again. The question was: "How much of our genome could be deleted without having any significant effect on our species?" The question was designed to find out whether Sandwalk readers believed in junk DNA or whether they were being persuaded by some scientists to think that most of our genome was essential. (Modern creationists are also promoting the death of junk DNA.) There was some dispute about the interpretation of the question but most readers took it to be a question about the amount of junk DNA.

Astonishingly, almost half of Sandwalk readers think that we need more than half of our genome to survive. This would be a surprise to a puffer fish.

I began a series of postings in order to explain what our genome actually looks like. So far we've determined that about 2.5% is essential and 53% is junk. Now it's time to finish off this particular theme and have another vote.

PZ points out that most of what we call junk DNA is not controversial. It consists of LINEs and SINES, which are (mostly) defective transposons. The pufferfish genome has a lot less of this kind of junk DNA than we do. This accounts for a good deal of the reduction n genome size that we see in modern pufferfish.

PZ also points out that we need to think differently about evolution ...

In the world of genomic housekeeping, the puffer fish is a neatnik who keeps the trash under control, while the rest of us are pack rats hoarding junk DNA.Well said PZ!!1

There's a lot of thought these days going into trying to figure out some adaptive reason for such a sorry state of affairs. None of it is particularly convincing. We'd be better off reconciling ourselves to the notion that much of evolution is random, and that nothing prevents nonfunctional complexity from simply accumulating.

Watch for a few more postings on the remaining 45% of our genome then get ready to vote again. I'm hoping for a better result next time!

1. I used to know someone named Paul Myers who would never had said such a thing on talk.origins. Any relation?

[Image Credit: The junk DNA icon is from the creationist website Evolution News & Views.]

Sunday, March 27, 2016

Georgi Marinov reviews two books on junk DNA

The books are ...

The Deeper Genome: Why there is more to the human genome than meets the eye, by John Parrington, (Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press), 2015. ISBN:978-0-19-968873-9.You really need to read the review for yourselves but here's a few teasers.

Junk DNA: A Journey Through the Dark Matter of the Genome, by Nessa Carey, (New York, United States: Columbia University Press), 2015. ISBN:978-0-23-117084-0.

If taken uncritically, these texts can be expected to generate even more confusion in a field that already has a serious problem when it comes to communicating the best understanding of the science to the public.Parrington claims that noncoding DNA was thought to be junk and Georgi replies,

However, no knowledgeable person has ever defended the position that 98 % of the human genome is useless. The 98 % figure corresponds to the fraction of it that lies outside of protein coding genes, but the existence of distal regulatory elements, as nicely narrated by the author himself, has been at this point in time known for four decades, and there have been numerous comparative genomics studies pointing to a several-fold larger than 2% fraction of the genome that is under selective constraint.I agree. That's a position that I've been trying to advertise for several decades and it needs to be constantly reiterated since there are so many people who have fallen for the myth.

Georgi goes on to explain where Parringtons goes wrong about the ENCODE results. This critique is devastating, coming, as it does, from an author of the most relevant papers.1 My only complaint about the review is that George doesn't reveal his credentials. When he quotes from those papers—as he does many times—he should probably have mentioned that he is an author of those quotes.

Georgi goes on to explain four main arguments for junk DNA: genetic load, the C-value Paradox, transposons (selfish DNA), and modern evolutionary theory. I like this part since it's similar to the Five Things You Should Know if You Want to Participate in the Junk DNA Debate. The audience of this journal is teachers and this is important information that they need to know, and probably don't.

His critique of Nessa Carey's book is even more devastating. It begins with,

Still, despite a few unfortunate mistakes, The Deeper Genome is well written and gets many of its facts right, even if they are not interpreted properly. This is in stark contrast with Nessa Carey’s Junk DNA: A Journey Through the Dark Matter of the Genome. Nessa Carey has a PhD in virology and has in the past been a Senior Lecturer in Molecular Biology at Imperial College, London. However, Junk DNA is a book not written at an academic level but instead intended for very broad audience, with all the consequences that the danger of dumbing it down for such a purpose entails.It gets worse. Nessa Carey claims that scientists used to think that all noncoding DNA was junk but recent discoveries have discredited that view. Georgi sets her straight with,

Of course, scientists have had a very good idea why so much of our DNA does not code for proteins, and they have had that understanding for decades, as outlined above. Only by completely ignoring all that knowledge could it have been possible to produce many of the chapters in the book. The following are referred to as junk DNA by Carey, with whole chapters dedicated to each of them (Table 3).You would think that this is something that doesn't have to be explained to biology teachers but the evidence suggests otherwise. One of those teachers recently reviewed Nessa Carey's book very favorably in the journal The American Biology Teacher and another high school teacher reveals his confusion about the subject in the comments to my post [see Teaching about genomes using Nessa Carey's book: Junk DNA].

The inclusion of tRNAs and rRNAs in the list of “previously thought to be junk” DNA is particularly baffling given that they have featured prominently as critical components of the protein synthesis machinery in all sorts of basic high school biology textbooks for decades, not to mention the role that rRNAs and some of the other noncoding RNAs on that list play in many “RNA world” scenarios for the origin of life. How could something that has so often been postulated to predate the origin of DNA as the carrier of genetic information (Jeffares et al. 1998; Fox 2010) and that must have been of critical importance both before and after that be referred to as “junk”?

It's good that Georgi Marinov makes this point forcibly.

Now I'm going to leave you with an extended quote from Georgi Marinov's review. Coming from a young scientist, this is very potent and it needs to be widely disseminated. I agree 100%.

The reason why scientific results become so distorted on their way from scientists to the public can only be understood in the socioeconomic context in which science is done today. As almost everyone knows at this point, science has existed in a state of insufficient funding and ever increasing competition for limited resources (positions, funding, and the small number of publishing slots in top scientific journals) for a long time now. The best way to win that Darwinian race is to make a big, paradigm shifting finding. But such discoveries are hard to come by, and in many areas might actually never happen again—nothing guarantees that the fundamental discoveries in a given area have not already been made. ... This naturally leads to a publishing environment that pretty much mandates that findings are framed in the most favorable and exciting way, with important caveats and limitations hidden between the lines or missing completely. The author is too young to have directly experienced those times, but has read quite a few papers in top journals from the 1970s and earlier, and has been repeatedly struck by the difference between the open discussion one can find in many of those old articles and the currently dominant practices.It's not easy to explain these things to a general audience, especially an audience that has been inundated with false information and false ideas. I'm going to give it a try but it's taking a lot more effort than I imagined.

But that same problem is not limited to science itself, it seems to be now prevalent at all steps in the chain of transmission of findings, from the primary literature, through PR departments and press releases, and finally, in the hands of the science journalists and writers who report directly to the lay audience, and who operate under similar pressures to produce eye-catching headlines that can grab the fleeting attention of readers with ever decreasing ability to concentrate on complex and subtle issues. This leads to compound overhyping of results, of which The Deeper Genome is representative, and to truly surreal distortion of the science, such as what one finds in Nessa Carey’s Junk DNA.

The field of functional genomics is especially vulnerable to these trends, as it exists in the hard-to-navigate context of very rapid technological changes, a potential for the generation of truly revolutionary medical technologies, and an often difficult interaction with evolutionary biology, a controversial for a significant portion of society topic. It is not a simple subject to understand and communicate given all these complexities while in the same time the potential and incentives to mislead and misinterpret are great, and the consequences of doing so dire. Failure to properly communicate genomic science can lead to a failure to support and develop the medical breakthroughs it promises to deliver, or what might be even worse, to implement them in such a way that some of the dystopian futures imagined by sci-fi authors become reality. In addition, lending support to anti-evolutionary forces in society by distorting the science in a way that makes it appear to undermine evolutionary theory has profound consequences that given the fundamental importance of evolution for the proper understanding of humanity’s place in nature go far beyond making life even more difficult for teachers and educators of even the general destruction of science education. Writing on these issues should exercise the needed care and make sure that facts and their best interpretations are accurately reported. Instead, books such as The Deeper Genome and Junk DNA are prime examples of the negative trends outlined above, and are guaranteed to only generate even deeper confusion.

1. Georgi Marinov is an author on the original ENCODE paper that claimed 80% of our genome is functional (ENCODE Project Consortium, 2012) and the paper where the ENCODE leaders retreated from that claim (Kellis et al., 2014).

ENCODE Project Consortium (2012) An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature, 48957-74. [doi: 10.1038/nature11247]

Kellis, M., Wold, B., Snyder, M.P., Bernstein, B.E., Kundaje, A., Marinov, G.K., Ward, L.D., Birney, E., Crawford, G.E., and Dekker, J. (2014) Defining functional DNA elements in the human genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. (USA) 111:6131-6138. [doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318948111]

Wednesday, June 22, 2022

The Function Wars Part IX: Stefan Linquist on Causal Role vs Selected Effect

How much of the human genome is functional? This a problem that will be solved by biochemists not epistemologists.

What is junk DNA? What is functional DNA? Defining your terms is a key part of any scientific controversy because you can't have a debate if you can't agree on what you are debating. We've been debating the prevalence of junk DNA for more than 50 years and much of that debate has been (deliberately?) muddled by one side or the other in order to score points. For example, how many times have you heard the ridiculous claim that all noncoding DNA was supposed to be junk DNA? And how many times have you heard that all transcripts must have a function merely because they exist?

Thursday, March 14, 2024

Nils Walter disputes junk DNA: (8) Transcription factors and their binding sites

I'm discussing a recent paper published by Nils Walter (Walter, 2024). He is arguing against junk DNA by claiming that the human genome contains large numbers of non-coding genes.

This is the seventh post in the series. The first one outlines the issues that led to the current paper and the second one describes Walter's view of a paradigm shift/shaft. The third post describes the differing views on how to define key terms such as 'gene' and 'function.' In the fourth post I discuss his claim that differing opinions on junk DNA are mainly due to philosophical disagreements. The fifth, sixth, and seventh posts address specific arguments in the junk DNA debate.

- Nils Walter disputes junk DNA: (1) The surprise

- Nils Walter disputes junk DNA: (2) The paradigm shaft

- Nils Walter disputes junk DNA: (3) Defining 'gene' and 'function'

- Nils Walter disputes junk DNA: (4) Different views of non-functional transcripts

- Nils Walter disputes junk DNA: (5) What does the number of transcripts per cell tell us about function?

- Nils Walter disputes junk DNA: (6) The C-value paradox

- Nils Walter disputes junk DNA: (7) Conservation of transcribed DNA

Friday, March 15, 2024

Nils Walter disputes junk DNA: (9) Reconciliation

I'm discussing a recent paper published by Nils Walter (Walter, 2024). He is arguing against junk DNA by claiming that the human genome contains large numbers of non-coding genes.

This is the ninth and last post in the series. I'm going to discuss Walker's view on how to tone down the dispute over the amount of junk in the human genome. Here's a list of the previous posts.

- Nils Walter disputes junk DNA: (1) The surprise

- Nils Walter disputes junk DNA: (2) The paradigm shaft

- Nils Walter disputes junk DNA: (3) Defining 'gene' and 'function'

- Nils Walter disputes junk DNA: (4) Different views of non-functional transcripts

- Nils Walter disputes junk DNA: (5) What does the number of transcripts per cell tell us about function?

- Nils Walter disputes junk DNA: (6) The C-value paradox

- Nils Walter disputes junk DNA: (7) Conservation of transcribed DNA

- Nils Walter disputes junk DNA: (8) Transcription factors and their binding sites

"Conclusion: How to Reconcile Scientific Fields"

Walter concludes his paper with some thoughts on how to deal with the controversy going forward. I'm using the title that he choose. As you can see from the title, he views this as a squabble between two different scientific fields, which he usually identifies as geneticists and evolutionary biologists versus biochemists and molecular biologists. I don't agree with this distinction. I'm a biochemist and molecular biologist, not a geneticist or an evolutionary biologist, and still I think that many of his arguments are flawed.

Let's see what he has to say about reconciliation.

Science thrives from integrating diverse viewpoints—the more diverse the team, the better the science.[107] Previous attempts at reconciling the divergent assessments about the functional significance of the large number of ncRNAs transcribed from most of the human genome by pointing out that the scientific approaches of geneticists, evolutionary biologists and molecular biologists/biochemists provide complementary information[42] was met with further skepticism.[74] Perhaps a first step toward reconciliation, now that ncRNAs appear to increasingly leave the junkyard,[35] would be to substitute the needlessly categorical and derogative word RNA (or DNA) “junk” for the more agnostic and neutral term “ncRNA of unknown phenotypic function”, or “ncRNAupf”. After all, everyone seems to agree that the controversy mostly stems from divergent definitions of the term “function”,[42, 74] which each scientific field necessarily defines based on its own need for understanding the molecular and mechanistic details of a system (Figure 3). In addition, “of unknown phenotypic function” honors the null hypothesis that no function manifesting in a phenotype is currently known, but may still be discovered. It also allows for the possibility that, in the end, some transcribed ncRNAs may never be assigned a bona fide function.

First, let's take note of the fact that this is a discussion about whether a large percentage of transcripts are functional or not. It is not about the bigger picture of whether most of the genome is junk in spite of the fact that Nils Walter frames it in that manner. This becomes clear when you stop and consider the implications of Walter's claim. Let's assume that there really are 200,000 functional non-coding genes in the human genome. If we assume that each one is about 1000 bp long then this amounts to 6.5% of the genome—a value that can easily be accommodated within the 10% of the genome that's conserved and functional.

Now let's look at how he frames the actual disagreement. He says that the groups on both sides of the argument provide "complementary information." Really? One group says that if you can delete a given region of DNA with no effect on the survival of the individual or the species then it's junk and the other group says that it still could have a function as long as it's doing something like being transcribed or binding a transcription factor. Those don't look like "complimentary" opinions to me.

His first step toward reconciliation starts with "now that ncRNAs appear to increasingly leave the junkyard." That's not a very conciliatory way to start a conversation because it immediately brings up the question of how many ncRNAs we're talking about. Well-characterized non-coding genes include ribosomal RNA genes (~600), tRNA genes (~200), the collection of small non-coding genes (snRNA, snoRNA, microRNA, siRNA, PiWi RNA)(~200), several lncRNAs (<100), and genes for several specialized RNAs such as 7SL and the RNA component of RNAse P (~10). I think that there are no more than 1000 extra non-coding genes falling outside these well-known examples and that's a generous estimate. If he has evidence for large numbers that have left the junkyard then he should have presented it.

Walter goes on to propose that we should divide non-coding transcripts into two categories; those with well-characterized functions and "ncRNA of unknown function." That's ridiculous. That is not a "agnostic and neutral term." It implies that non-conserved transcripts that are present at less that one copy per cell could still have a function in spite of the fact that spurious transcription is well-documented. In fact, he basically admits this interpretation at the end of the paragraph where he says that using this description (ncRNA of unknown function) preserves the possibility that a function might be discovered in the future. He thinks this is the "null hypothesis."

The real null hypothesis is that a transcript has no function until it can be demonstrated. Notice that I use the word "transcript" to describe these RNAs instead of "ncRNA" or "ncRNA of unknown phenotypic function." I don't think we lose anything by using the word "transcript."

Walter also address the meaning of "function" by claiming that different scientific fields use different definitions as though that excuses the conflict. But that's not an accurate portrayal of the problem. All scientists, no matter what field they identify with, are interested in coming up with a way of identifying functional DNA. There are many biochemists and molecular biologists who accept the maintenance definition as the best available definition of function. As scientists, they are more than willing to entertain any reasonable scientific arguments in favor of a different definition but nobody, including Nils Walter, has come up with such arguments.

Now let's look at the final paragraph of Walter's essay.

Most bioscientists will also agree that we need to continue advancing from simply cataloging non-coding regions of the human genome toward characterizing ncRNA functions, both elementally and phenotypically, an endeavor of great challenge that requires everyone's input. Solving the enigma of human gene expression, so intricately linked to the regulatory roles of ncRNAs, holds the key to devising personalized medicines to treat most, if not all, human diseases, rendering the stakes high, and unresolved disputes counterproductive.[108] The fact that newly ascendant RNA therapeutics that directly interface with cellular RNAs seem to finally show us a path to success in this challenge[109] only makes the need for deciphering ncRNA function more urgent. Succeeding in this goal would finally fulfill the promise of the human genome project after it revealed so much non-protein coding sequence (Figure 1). As a side effect, it may make updating Wikipedia and encyclopedia entries less controversial.

I agree that it's time for scientists to start identifying those transcripts that have a true function. I'll go one step further; it's time to stop pretending that there might be hundreds of thousands of functional transcripts until you actually have some data to support such a claim.

I take issue with the phrase "solving the enigma of human gene expression." I think we already have a very good understanding of the fundamental mechanisms of gene expression in eukaryotes, including the transitions between open and closed chromatin domains. There may be a few odd cases that deviate from the norm (e.g. Xist) but that hardly qualifies as an "enigma." He then goes on to say that this "enigma" is "intricately linked to the regulatory roles of ncRNAs" but that's not a fact, it's what's in dispute and why we have to start identifying the true function (if any) of most transcripts. Oh, and by the way, sorting out which parts of the genome contain real non-coding genes may contribute to our understanding of genetic diseases in humans but it won't help solve the big problem of how much of our genome is junk because mutations in junk DNA can cause genetic diseases.

Sorting out which transcripts are functional and which ones are not will help fill in the 10% of the genome that's functional but it will have little effect on the bigger picture of a genome that's 90% junk.

We've known that less than 2% of the genome codes for proteins since the late 1960s—long before the draft sequence of the human genome was published in 2001—and we've known for just as long that lots of non-coding DNA has a function. It would be helpful if these facts were made more widely known instead of implying that they were only dscovered when the human genome was sequenced.

Once we sort out which transcripts are functional, we'll be in a much better position to describe the all the facts when we edit Wikipedia articles. Until that time, I (and others) will continue to resist the attempts by the students in Nils Walter's class to remove all references to junk DNA.

Walter, N.G. (2024) Are non‐protein coding RNAs junk or treasure? An attempt to explain and reconcile opposing viewpoints of whether the human genome is mostly transcribed into non‐functional or functional RNAs. BioEssays:2300201. [doi: 10.1002/bies.202300201]

Sunday, November 01, 2015

More stupid hype about lncRNAs

They did no such thing. What they discovered was about 3,000 previously unidentified transcripts expressed at very low levels in human B cells and T cells. They declared that these low-level transcripts are lncRNAs and they assumed that the complementary DNA sequences were genes. Their actual result identifies 3,000 bits of the genome that may or may not turn out to be genes. They are PUTATIVE genes.

None of that deterred Karen Ring who blogs at The Stem Cellar: The Official Blog of CIRM, California's Stem Cell Agency. Her post on this subject [UCLA Scientists Find 3000 New Genes in “Junk DNA” of Immune Stem Cells] begins with ...

Friday, March 25, 2016

Teaching about genomes using Nessa Carey's book: Junk DNA

Today, while searching for articles on junk DNA, I came across a review of Nessa Carey's book published in The American Biology Teacher: DNA. The review was written by teacher in Colorado and she liked the book very much. Here's the opening paragraph,

The term junk DNA has been used to describe DNA that does not code for proteins or polypeptides. Recent research has made this term obsolete, and Nessa Carey elaborates on a wide spectrum of examples of ways in which DNA contributes to cell function in addition to coding for proteins. As in her earlier book, The Epigenetics Revolution (reviewed by ABT in 2013), Carey uses analogies and diagrams to relate complicated information. Although she unavoidably uses some jargon, she provides the necessary background for the nonbiologist.The author of the review does not question or challenge the opinions of Nessa Carey and, if you think about it, that's understandable. The average biology teacher will assume that a book written by a scientist must be basically correct or it wouldn't have been published.

That's not true, as most Sandwalk readers know. You would think that biology educators should know this and exercise a little skepticism when reviewing books. Ideally, the book reviews should be written by experts who can evaluate the material in the book.

Now we have a problem. The way to correct false information about genomes and junk DNA is to teach it correctly in high school and university courses. But that means we first have to teach the teachers. Here's a case where professional teachers have been bamboozled by a bad book and that's going of make it even more difficult to correct the problem.

The last paragraph of the review shows us what influence a bad book can have,

As a biology teacher who enjoys sharing with students some details that go beyond the textbook or that challenge dogma, I enthusiastically read multiple chapters at each sitting, making note of what I cannot wait to add to class discussions. “Junk DNA” may be a misnomer, but Junk DNA is an excellent way of finding out why.Oh dear. It's going to be hard to re-educate those students once their misconceptions have been reinforced by a teacher they respect.

Sunday, September 16, 2012

Read What Mike White Has to Say About ENCODE and Junk DNA

Mike published an impressive article on the Huffington Post a few days ago. This is a must-read for anyone interested in the controversy over junk DNA: A Genome-Sized Media Failure. Here's part of what he says ...

If you read anything that emerged from the ENCODE media blitz, you were probably told some version of the "junk DNA is debunked" story. It goes like this: When scientists realized that classical, protein-encoding genes make up less than 2% of the human genome, they simply assumed, in a fit of hubris, that the rest of our DNA was useless junk. (You might have also heard this from your high school or college teacher. Your teacher was wrong.) Along came the ENCODE consortium, which found that, far from being useless, junk DNA is packed with functionality. And so everything scientists thought they knew about the genome was wrong, wrong wrong.Way to go, Mike!

The Washington Post headline read, "'Junk DNA' concept debunked by new analysis of human genome." The New York Times wrote that "The human genome is packed with at least four million gene switches that reside in bits of DNA that once were dismissed as 'junk' but that turn out to play critical roles in controlling how cells, organs and other tissues behave." Influenced by misleading press releases and statements by scientists, story after story suggested that debunking junk DNA was the main result of the ENCODE studies. These stories failed us all in three major ways: they distorted the science done before ENCODE, they obscured the real significance of the ENCODE project, and most crucially, they mislead the public on how science really works.

What you should really know about the concept of junk DNA is that, first, it was not based on what scientists didn't know, but rather on what they did know about the genome; and second, that concept has held up quite well, even in light of the ENCODE results.

In the past week, lot's of scientists have demonstrated that they don't know what they're talking about when they make statements about junk DNA. I don't expect any of those scientists to apologize for misleading the public. After all, their statements were born of ignorance and that same ignorance prevents them from learning the truth, even now.

However, I do expect lots of science journalists to write follow-up articles correcting the misinformation that they have propagated. That's their job.

Thursday, June 14, 2007

Catherine Shaffer Responds to My Comments About Her WIRED Article

Over on the WIRED website there's a discussion about the article on junk DNA [One Scientist's Junk Is a Creationist's Treasure]. In the comments section, the author Catherine Shaffer responds to my recent posting about her qualifications [see WIRED on Junk DNA]. She says,

You might be interested to learn that I contacted Larry Moran while working on this article and after reading the archives of his blog. I wanted to ask him to expand upon his assertion that junk DNA disproves intelligent design. His response was fairly brief, did not provide any references, and did not invite further discussion. It's interesting that he's now willing to write a thousand words or so about how wrong I am publicly, but was not able to engage this subject privately with me.Catherine Shaffer sent me a brief email message where she mentioned that she had read my article on Junk DNA Disproves Intelligent Design Creationism. She wanted to know more about this argument and she wanted references to those scientists who were making this argument. Ms. Shaffer mentioned that she was working on an article about intelligent design creationism and junk DNA.

I responded by saying that the presence of junk DNA was expected according to evolution and that it was not consistent with intelligent design. I also said that, "The presence of large amounts of junk DNA in our genome is a well established fact in spite of anything you might have heard in the popular press, which includes press releases." She did not follow up on my response.

His blog post is inaccurate in a couple of ways. First, I did not make the claim, and was very careful to avoid doing so, that “most” DNA is not junk. No one knows how much is functional and how much is not, and none of my sources would even venture to speculate upon this, not even to the extent of “some” or “most.”Her article says, "Since the early '70s, many scientists have believed that a large amount of many organisms' DNA is useless junk. But recently, genome researchers are finding that these "noncoding" genome regions are responsible for important biological functions." Technically she did not say that most DNA is not junk. She just strongly implied it.

I find it difficult to believe that Ryan Gregory would not venture to speculate on the amount of junk DNA but I'll let him address the validity of Ms. Shaffer's statement.

Moran also mistakenly attributed a statement to Steven Meyer that Meyer did not make.I can see why someone might have "misunderstood" my reference to what Myer said so I've edited my posting to make it clear.

Judmarc and RickRadditz—Here is a link to the full text of the genome biology article on the opossum genome: Regulatory conservation of protein coding and microRNA genes in vertebrates: lessons from the opossum genome. We didn't have space to cover this in detail, but in essence what the researchers found was that upstream intergenic regions were more highly conserved in the possum compared to coding regions, but also represented a greater area of difference between possums and humans.This appears to be a reference to the paper she was discussing in her article. It wasn't at all clear to me that this was the article she was thinking about in the first few paragraphs of her WIRED article.

Interested readers might want to read the comment by "Andrea" over on the WIRED site.

So, yes, this does run counter to the received wisdom, which makes it fascinating. You are right that the discussion of junk vs. nonjunk and conserved vs. nonconserved is much more nuanced, and we really couldn't do it justice in this space. Here is another reference you might enjoy that begins to deconstruct even our idea of what conservation means: “Conservation of RET regulatory function from human to zebrafish without sequence similarity.” Science. 2006 Apr 14;312(5771):276-9. Epub 2006 Mar 23. Revjim—If you have found typographical errors in the copy, please do point them out to us. The advantage of online publication is that we do get a chance to correct these after publication.Sounds to me like Catherine Shaffer is grasping at straws (or strawmen).

For Katharos and others—I interviewed five scientists for this article. Dr. Francis Collins, Dr. Michael Behe, Dr. Steve Meyers, Dr. T. Ryan Gregory, and Dr. Gill Bejerano. Each one is a gentleman and a credentialed expert either in biology or genetics. I am grateful to all of them for their time and kindness.I think we all know just how "credentialed" Stephen Meyer is. He has a Ph.D. in the history and philosophy of science. Most of us are familiar with the main areas of expertise of Michael Behe and none of them appear to be science.

Tuesday, March 13, 2018

Making Sense of Genes by Kostas Kampourakis

Kostas Kampourakis is a specialist in science education at the University of Geneva, Geneva (Switzerland). Most of his book is an argument against genetic determinism in the style of Richard Lewontin. You should read this book if you are interested in that argument. The best way to describe the main thesis is to quote from the last chapter.

Here is the take-home message of this book: Genes were initially conceived as immaterial factors with heuristic values for research, but along the way they acquired a parallel identity as DNA segments. The two identities never converged completely, and therefore the best we can do so far is to think of genes as DNA segments that encode functional products. There are neither 'genes for' characters nor 'genes for' diseases. Genes do nothing on their own, but are important resources for our self-regulated organism. If we insist in asking what genes do, we can accept that they are implicated in the development of characters and disease, and that they account for variation in characters in particular populations. Beyond that, we should remember that genes are part of an interactive genome that we have just begun to understand, the study of which has various limitations. Genes are not our essences, they do not determine who we are, and they are not the explanation of who we are and what we do. Therefore we are not the prisoners of any genetic fate. This is what the present book has aimed to explain.

Saturday, March 02, 2024

Nils Walter disputes junk DNA: (4) Different views of non-functional transcripts

I'm discussing a recent paper published by Nils Walter (Walter, 2024). He is trying to explain the conflict between proponents of junk DNA and their opponents. His main focus is building a case for large numbers of non-coding genes.

This is the third post in the series. The first one outlines the issues that led to the current paper and the second one describes Walter's view of a paradigm shift. The third post describes the differing views on how to define key terms such as 'gene' and 'function.' In this post I'll describe the heart of the dispute according to Nils Walter.

-Nils Walter disputes junk DNA: (1) The surprise

-Nils Walter disputes junk DNA: (2) The paradigm shaft

-Nils Walter disputes junk DNA: (3) Defining 'gene' and 'function'

Wednesday, November 03, 2021

What's in your genome?: 2021

This is an updated version of what's in your genome based on the latest data. The simple version is ...

about 90% of your genome is junk

Sunday, October 15, 2023

Only 10.7% of the human genome is conserved

The Zoonomia project aligned the genome sequences of 240 mammalian species and determined that only 10.7% of the human genome is conserved. This is consistent with the idea that about 90% of our genome is junk.

The April 28, 2023 issue of science contains eleven papers reporting the results of a massive study comparing the genomes of 240 mammalian species. The issue also contains a couple of "Perspectives" that comment on the work.

Wednesday, November 11, 2015

Pwned by lawyers (not)

Barry Arringotn took exception and challenged me in: Larry Moran's Irony Meter.

OK, Larry. I assume you mean to say that I do not understand the basics of Darwinism. I challenge you, therefore, to demonstrate your claim.This was the kind of challenge that's like shooting fish in a barrel but I thought I'd do it anyway in case it could serve as a teaching moment. Boy, was I wrong! Turns out that ID proponents are unteachable.

I decided to concentrate on Arrington's published statements about junk DNA where he said ...

Wednesday, September 26, 2007

Will the IDiots Make the Same Mistake with RNA that They Made with Junk DNA?

Robert Crowther (whoever that is) posted a similar question on the Intelligent Design Creationis blog of the Discovery Institute. His question was Will Darwinists Make the Same Mistake with RNA that They Made in Ignoring So-Called "Junk" DNA?.

Robert Crowther (whoever that is) posted a similar question on the Intelligent Design Creationis blog of the Discovery Institute. His question was Will Darwinists Make the Same Mistake with RNA that They Made in Ignoring So-Called "Junk" DNA?.One interesting thing that leapt out at me when reading this was the fact that, while many scientists now realize that it was a mistake to jump to the conclusion that there were massive amounts of "junk" in DNA (because they were trying to fit the research into a Darwinian model), they are on the verge of committing the same exact mistake all over again, this time with RNA.In order to understand such a bizarre question you have to put yourself in the shoes of an IDiot. They firmly believe that the concept of junk DNA has been overturned by recent scientific results. According to them, the predictions of Intelligent Design Creationism have been vindicated and all of the junk DNA has a function.

Of course this isn't true but, unfortunately, there are some scientists whose level of intelligence is not much above that of the typical IDiot [Junk DNA in New Scientist] [The Role of Ultraconserved Non-Coding Elements in Mammalian Genomes].

Now the IDiots have turned their attention to RNA. They fell hook line and sinker for the hype about functional sequences in junk DNA and they're falling just as easily for the hype about new RNAs. They believe all those silly papers that attribute function to every concevable RNA molecule that has ever been predicted or detected in some assay.

The IDiots were wrong about junk DNA and they're wrong about RNA. The answer to my question is "yes," the IDiots will make the same mistake. You can practically count on it. The answer to Crowther's question is "no." Most (but not all) scientists did not fall for the spin on junk DNA and they realize that the vast majority of our genome is junk. In the long run, they will not fall for the claim that most of the junk DNA is functional because it encodes essential RNA molecules.