Philip Ball believes that we are in the middle of a revolution in our way of thinking about how life works. His ideas are complex but part of his case involves molecular biology and how things work at the molecular level. Ball believes that the old view of molecular biology placed far too much emphasis on coding DNA and ignored all the other functional regions of genomes. He also says that most of our genes specify non-coding RNA instead of mRNA and implies to his readers that a very large fraction of our genome is functional (i.e. not junk).1

In order to build the case for revolution, he tries to demonstrate a paradigm shift in our view of molecular biology by showing a huge gap between the understanding of previous generations of molecular biologists and the post-genomic view. I believe he is wrong about this for two reasons: first, he misrepresents the views of older molecular biologists and, second he misrepresents the discoveries of the past twenty years. I tried to explain why he was wrong about these two claims in a previous post where I discussed an article he published in Scientific American in May 2024: Philip Ball says RNA may rule our genome.

Philip Ball responded to my criticism in a comment under that article.

Older molecular biologists were really stupid

I said ...

Ball begins with the same old myth that writers like him have been repeating for many years. He claims that before ENCODE most molecular biologists were really stupid. According to Philip Ball, most of us thought that coding DNA was the only functional part of the genome and most of the rest was junk DNA.

In the comment section of my earlier post, Philip Ball says,

I’m sorry to say that Larry’s commentary here is dismayingly inaccurate.

Let’s get this one out of the way first:

“He claims that before ENCODE most molecular biologists were really stupid.”

I have never made this claim and never would – it is a pure fabrication on Larry’s part. I guess this is what John Horgan meant in his comment to Larry: credible writers don’t just make up stuff.

I admit that Philip Ball never said those exact words. I'll leave it to the readers to decide whether my characterization of his position is accurate.

I stand by the statements I made although I admit to a bit of hyperbole. Ball has said repeatedly that the molecular biologists of my generation were wedded to the idea that coding regions were the only important part of the genome and he often connects that to the Central Dogma of Molecular Biology. He also claims that the experts in molecular biology dismissed all non-coding DNA as junk. Here's how he puts it in another article that he published recently in Aeon: We are not machines.

Only around 1-2 per cent of the entire human genome actually consists of protein-coding genes. The remainder was long thought to be mostly junk: meaningless sequences accumulated over the course of evolution. But at least some of that non-coding genome is now known to be involved in regulating genes: altering, activating or suppressing their transcription in RNA and translation into proteins.

I interpret that to mean that older molecular biologists, like me, didn't know about functional non-coding DNAs such as centromeres, telomeres, origins of replication, non-coding genes, SARs, and regulatory sequences in spite of the fact that thousands of papers on these sequences were published in the 30 years that preceded the publication of the first draft of the human genome sequence. This is not true, we did know about those things. I don't think it's too much of an exaggeration to say that Philip Ball thinks we were really stupid.

Here's what he says in his book, "How Life Works" (p. 85) when he's talking about the beginning of the human genome project.

Even at its outset, it faced the somewhat troubling issue that just 2 percent or so of our genome actually accounts for protein-coding genes. The conventional narrative was that our biology was all about proteins, for each of which the genome held the template. ... But we had all this other DNA too! What was it for? The common view was that it was mostly just junk, like the stuff in our attics: meaningless material accumulated during evolution, which our cells had no motivation to clear out.

Again, his claim is that in 1990 at the beginning of the human genome project the experts in molecular biology thought that non-coding DNA was mostly junk (98% of the genome). I have repeatedly refuted this myth and challenged anyone to come up with a single scientific paper arguing that all non-coding DNA is junk. I challenge Philip Ball to find a single molecular biology textbook written before 1990 that fails to discuss regulation, non-coding genes, and other non-coding functional elements in the human genome.

The truth is that the molecular biology experts concluded in the 1970s that we had about 30,000 genes and that 90% of our genome is junk and 10% is functional. That 10% consisted of about 2% coding DNA (now thought to be only 1%) and 8% functional non-coding DNA. So the "conventional narrative" was that there was a lot more functional non-coding DNA than coding DNA.

The human genome is full of genes for regulatory RNAs.

"Ball is one of the most meticulous, precise science writers out there. He is the antithesis of hypey, "dumb-it-down" reporting. He is MUCH more credible than you are, Laurence."

John Horgan July, 2024The title of the article I was discussing is "Revolutionary Genetics Research Shows RNA May Rule Our Genome." In that article Ball says that ENCODE was basically right and there are many more non-coding genes than protein-coding genes. I pointed out that Ball mentions some criticism of this idea but only to dismiss it. I said that "[Ball] wants you to believe that almost of all of those transcripts are functional—that's the revolution that he's promoting." Philip Ball objects to this statement ...

This too is sheer fabrication. I don’t say this in my article, nor in my book. Instead, I say pretty much what Larry seems to want me to say, but for some reason he will not admit it – which is that there is controversy about how many of the transcripts are functional."

Ball states that "ENCODE was basically right" when they claimed that 75% of our genome was transcribed and he goes on to say that ...

Dozens of other research groups, scoping out activity along the human genome, also have found that much of our DNA is churning out 'noncoding' RNA.

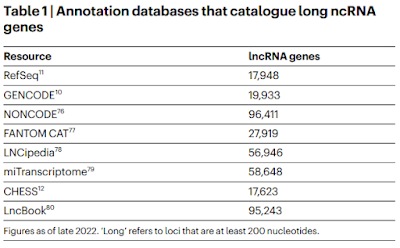

He says that ENCODE has identified 37,000 noncoding genes but there may be as many as 96,000. After making these definitive statements, he mentions that there are "still doubters" but then discuss why these discoveries are revolutionary. Later on he quotes John Mattick suspecting that there may be more that 500,000 non-coding genes.

Toward the end of the article, after discussing all kinds of functional RNAs, he brings up the Ponting and Haerty review where they say that most lncRNAs are just noise. He also mentions that the low copy number of non-coding RNAs raises questions about whether they are functional but immediately counters with the standard excuses from his allies.

Ball closes the article with ...

Gingeras says he is perplexed by ongoing claims that ncRNAs are merely noise or junk, as evidence is mounting that they do many things. "It is puzzling why there is such an effort to persuade colleagues to move from a sense of interest and curiosity in the ncRNA field to a more dubious and critical one," he says.

Perhaps the arguments are so intense because they undercut the way we think our biology works. Ever since the epochal discovery about DNA's double helix and how it encodes information, the bedrock idea of molecular biology has been that there are precisely encoded instructions that program specific molecules for particular tasks. But ncRNAs seem to point to a fuzzier, more collective, logic to life. It is a logic that is harder to discern and harder to understand. ut if scientists can learn to live with the fuzziness, this view of life may turn out to be more complete.

What's remarkable about the quote from a leading ENCODE worker (Gingeras) is that he is "puzzled" by scientists who are dubious and critical about claims in the ncRNA field. Isn't that what good scientists are supposed to do? Isn't that exactly what we did when we successfully challenged the dubious claims about junk DNA made in 2012?

There is no doubt in my mind that Philip Ball has fallen hook-line-and-sinker for the ENCODE claims that our genome is buzzing with non-coding genes. He only brings up the counter-arguments to dismiss them and pretend that he is being fair. Nobody who was truly skeptical about the function of transcripts would write an article with the title, "Revolutionary Genetics Research Shows RNA May Rule Our Genome."

However, as Ball points out in other comments, he does have a sentence in his book where he mentions that perhaps only 30% of the genome is functional. He says in the comment that what he believes is that the amount of functional DNA lies somewhere between 10% and 30%. That's not something that he mentions in the Scientific American article but, if he's being honest, it does mean that I was unfair when I said he believes that "almost of all of those transcripts are functional" but I only know that from what he now says, not from the published article.

If I were to take Philip Ball at his word—as expressed in the comment—then he must believe that most of the ENCODE transcripts are junk RNA. That's not a belief that you get from reading his published work.2 Furthermore, if I were to take him at his word, then he must believe that there are some reasonable criteria that must be applied to a transcript in order to decide whether it has a biologically relevant function. So, when he says that ENCODE identified 37,600 non-coding genes he must have these criteria in mind but he doesn't express any serious skepticism about that number. We all know that there's no solid evidence that such a large number of transcripts are functional but that doesn't bother Philip Ball. He thinks we are in the middle of an RNA revolution.

1. In commenting to my previous post, Ball says he believes that somewhere between 70% and 90% of our genome is junk but he doesn't say this in the Scientific American article. Instead, he says that scientists were surprised to learn that 75% of the human genome is transcribed implying that there's a lot of function. He goes on the say that "ENCODE was basically right." But what the ENCODE publicity campaign actually said was that junk DNA is dead and there's practically no junk DNA. If Ball really believes that up to 90% of the genome is junk then to me this means that ENCODE was spectacularly wrong not "basically right."

2. Ball says that 75% of the genome is transcribed. If Ball believes that as little as 10% may be functional then he must believe that less than 10% is transcribed to produce functional RNAs since he has to allow for regulatory sequences and other functional DNA elements. Let's say that 8% is a reasonable number. Ball seems to be willing to admit that 67% of the genome might be transcribed to produce junk RNA.