Ford introduced the topic from three perspectives: science, philosophy, and politics. The science is straightforward. You can construct perfectly respectable gene trees for bacteria using all kinds of different genes. Problem is, the trees aren't congruent. They don't agree with each other. This is well-established scientific fact and you need to accept it if you're ever going to understand the issue.

The trees aren't wildly different in most cases and it's possible to make sense of them by postulating the transfer of genes from one species to a different species. This is horizontal gene transfer (HGT), as opposed to the normal vertical gene transfer from generation to generation. It's more common to use the term lateral gene transfer (LGT). There are three very well studied modes of transfer: conjugation, transduction, and transformation.

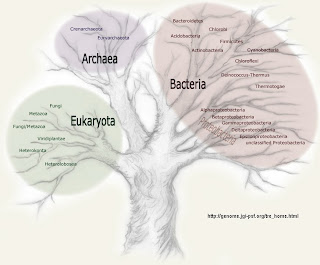

The scientific evidence shows clearly that early phylogenetic relationships among bacteria cannot be accurately represented by a single tree. The proper relationship is a net, network, or a web. Again, this is not controversial among those scientists who are aware of the data. The facts and the conclusion have been around for over a decade. There is no "tree of life" representing the early evolution of life on Earth.

The philosophical questions have to do with the usefulness of metaphors in science (e.g. tree) and the implications for understanding the history of biology. Do we need to abandon all talk of trees? Is "Darwinism" committed to tree-like interpretations of evolution? Ford spent more time than I would have liked discussing Darwin's thoughts about trees and, unfortunately, the famous New Scientist cover was prominently on display.

Later on, Ford made the point that we need to move beyond Darwinism to postDarwinism and I agree with this point. That's why we need to stop talking about what Charles Darwin did, or did not, believe. He was wrong about a lot of things, but he died over 125 years ago.

The politics part of the talk refers to the fact that questioning the tree of life cases problems for those who are fighting creationists. By challenging a fundamental concept in evolutionary biology we are lending support to the creationists. Ford said that he understands why Genie Scott and the people at NCSE might be upset about this and he understands why there might be some value in focusing on the validity of animal trees instead of drawing attention to the problems with bacterial trees.

Most people at the meeting felt that NSCE and everyone else involved in fighting creationists just have to suck it up and deal with the scientific facts.

The next talk was by Jan SappProfessor of Biology at York University in Toronto (ON, Canada). Sandwalk readers will recall that I devoted several postings to discussing his book on the Three Domain Hypothesis some years ago.

The next talk was by Jan SappProfessor of Biology at York University in Toronto (ON, Canada). Sandwalk readers will recall that I devoted several postings to discussing his book on the Three Domain Hypothesis some years ago. The title of Jan's talk was Thinking laterally on the tree of life. He emphasized history of trees in biology and the history of lateral gene transfer, including hybridization and symbiosis. As it turns out, scientists have been thinking about non-treelike inheritance for more than 100 years.

Jan has a new book coming out that will discuss this history and its implications for a new view of evolution.

The third speaker was Ian Hacking, Professor of Philosophy at the University of Toronto (ON, Canada). He talked about The Fatal Attraction of Trees. The idea is that we all have a preference for organizing information in a treelike manner and this bias gets in the way of accepting a different view of evolution.

Olivier Rieppel works at the Field Museum in Chicago (IL, USA). His talk was about The series,the network, and the tree: Changing metaphors of order in nature. Olivier spent some time on cladism and cladistics and raised interesting questions about the validity of cladism as an approach to phylogeny.

Here's the problem: even in vertebrates, the gene trees don't always agree with the morphological trees. Olivier works with snakes and lizards and sorting out the "true" evolutionary history is extremely difficult. Is there a lot of LGT in vertebrates? Is it possible that we might have to abandon trees even at the this level?

Rob Beiko works in the Faculty of Computer Science at Dalhousie University in Halifax (NS, Canada). He showed us how LGT can mess up your trees. He developed computer simulations to illustrate the effect of lateral genes transfer under various condition. The good news is that reasonable frequencies of lateral gene transfer don't completely obscure the underlying treelike phylogeny.

Yan Boucher is a postdoc at MIT in Boston (MA, USA). His talk was Evolutionary Units: Breaking down species concepts. The main idea was that we should not consider species as the unit of evolution, instead, the appropriate unit is a piece of DNA. This was by far the most controversial talk. Several participants, including me, were quite confused by the presentation. We weren't aware of the fact that a species was considered a unit of evolution.

The next speaker was Peter Gogarten of the University of Connecticut in Storrs (CT, USA). Peter showed us many examples of lateral gene transfer in bacteria.

Joe Velasco is in the Dept. of Philosophy at Stanford University in Palo Alto (CA, USA). He told us about strategies for Inferring phylogenetic networks from a hypothetical computational approach. The bottom line is that it make be possible to construct networks—as opposed to trees—using computer programs but it's going to take a huge amount of effort.

After the talks we retired to the pub at the University Club and dinner in the dining room (salmon). There's was much conversation. At my table the most interesting debates were about sex and race with Andrew Roger and Ford Doolottle.

And so endeth the first day.

In this post you say of Yan Boucher's talk, "The main idea was that we should not consider species as the unit of evolution, instead, the appropriate unit is a piece of DNA. This was by far the most controversial talk. Several participants, including me, were quite confused by the presentation. We weren't aware of the fact that a species was considered a unit of evolution."

ReplyDeleteBut a couple of posts down, you quote Ford Doolittle as saying, "[W]hat molecular phylogeny ultimately seeks is The Tree of Cells (TOC), a tracing back from the present of all speciation events...."

Could it have been in this sense that Yan Boucher spoke of species as a unit of evolution, i.e., that we detect and follow the occurrence of evolution through speciation events?

Wow, sounds like a fascinating day!

ReplyDeleteFord may be right that we can't infer a basal tree for all organisms from the sequences of extant organisms. But this doesn't mean that basal evolution was not tree-like, any more than the abundance of transfered sequences in extant microbial genomes means that most microbial inheritance is now by LGT.

ReplyDeleteWe know that vertical inheritance is vastly more frequent in extant bacteria than LGT, so we shouldn't rashly assume otherwise for ancient microbes (no matter how cool the idea is).

What's needed is some serious simulation work, to determine whether rare ancient LGT can mask tree-like inheritance. What would a billion years of evolution look like if one gene was transfered by LGT per 1000 organismal replications, or per 1,000,000 organismal replications?

There's no point in fussing about philosophy or politics until we know how much LGT would be needed to give the evolutionary relationships we see.

People have been inferring phylogenetic networks for years - nothing new there. The problem is that the principled ways are computationally feasible only for a handful of taxa. There are also fast, heuristic ways, but they leave questions in terms of interpretation and reliability.

ReplyDeleteHave a look at the recombination and viral evolution literature. There's really not much difference between recombination in viruses and LGT in bacteria - I'm wondering if some of the bacterial folk are in danger of reinventing the wheel here.

We weren't aware of the fact that a species was considered a unit of evolution.

ReplyDeleteWhat do you mean by that? You know better than that, Larry—of course in the study of macroevolution and paleontology species are considered the "natural" units of evolution.

While it is certainly true that many very good network methods have been developed to examine recombination, these methods are still improving as well, and in many cases are heuristic or need arbitrary thresholds to be chosen (e.g., median networks).

ReplyDeleteNetworks that represent non-homologous LGT are not exactly analogous to recombination networks too, given the possibility of drastic changes in gene content in the former.

Hi Larry -- you concede at various points that disagreements are often not huge, and that much of the pattern even in high-LGT situations is still treelike. Yet you persist in making unqualified declarations about the death of the tree of life -- much like the sensationalist cover of New Scientist -- despite the fact that you yourself regularly bash New Scientist for sensationalism and hype on almost every other topic!

ReplyDeleteWhy can't we be a little sophisticated about this, admit that "right" and "wrong" come in degrees in science, and that this applies to the Tree of Life metaphor like everything else.

In other words, why not apply some balance along the lines of Asimov's famous line?

"[W]hen people thought the earth was flat, they were wrong. When people thought the earth was spherical, they were wrong. But if you think that thinking the earth is spherical is just as wrong as thinking the earth is flat, then your view is wronger than both of them put together."

Isaac Asimov (1989). "The Relativity of Wrong." The Skeptical Inquirer, 14(1), 35-44. Fall 1989.

http://chem.tufts.edu/AnswersInScience/RelativityofWrong.htm

NickM says,

ReplyDeleteHi Larry -- you concede at various points that disagreements are often not huge, and that much of the pattern even in high-LGT situations is still treelike. Yet you persist in making unqualified declarations about the death of the tree of life -- much like the sensationalist cover of New Scientist -- despite the fact that you yourself regularly bash New Scientist for sensationalism and hype on almost every other topic!

Sorry if I haven't been clear.

One of the things I'm trying to do is to show everyone that there is a legitimate scientific controversy about the tree metaphor. The people at the meeting are not a bunch of kooks. There really is a problem that's due largely to the confounding effects of lateral gene transfer.

My own position is that the root of the tree of life is unknown and it will probably always be unknowable. The best representation of the total tree of life has a web or net at the base.

Thus, the so-called "tree of life" that's found in most textbooks—the one with three domains and eukaryotes on the same branch as archaebacteria—is almost certainly false.

In that sense the "tree of life" is deader than a doornail. However, this does not mean the end of all treelike thinking in biology. The upper parts of the representation are very treelike.

Some scientists would dispute this point of view and they cannot be as easily dismissed as you seem to think.

Rob - I agree; my point was that these ideas are not new, but already in the iterative improvement stage. This is in contrast to the impression created by the post: referring to a "hypothetical computational approach" and saying it "may be possible to construct networks—as opposed to trees—using computer programs" sounds strange when we have been doing it (albeit imperfectly) for years.

ReplyDeleteKonrad: good point, the talk was indeed about a hypothetical computational approach (seeded maximum likelihood inference of phylogenetic networks) which may have been implemented already (Luay Nakhleh? Barbara Holland? Daniel Huson?) but I haven't had time to check.

ReplyDeleteBut it's true that almost everyone and their poodle has tried out neighbor-net, MJ, split decomposition nets, etc. etc., by now.