"Epigenetics" is the (relatively) new buzzword. Old-fashioned genetics is boring so if you want to convince people (and grant agencies) that you're on the frontlines of research you have to say you're working on epigenetics. Even better, you can tell them that you are on the verge of overthrowing Darwinism and bringing back Jean-Baptiste Lamarck.

But you need to be careful if you adopt this strategy. Don't let anyone pin you down by defining "epigenetics." It's best to leave it as ambiguous as possible so you can adopt the Humpty-Dumpty strategy.1 Sarah C.P. Williams made that mistake a few years ago and incurred the wrath of Mark Ptashne [Core Misconcept: Epigenetics].More Recent Comments

Saturday, January 07, 2017

Friday, January 06, 2017

Genetic variation in the human population

With a current population size of over 7 billion, the human population should contain a huge amount of genetic variation. Most of it resides in junk DNA so it's of little consequence. We would like to know more about the amount of variation in functional regions of the genome because it tells us something about population genetics and evolutionary theory.

A recent paper in Nature (Aug. 2016) looked at a large dataset of 60,706 individuals. They sequenced the protein-coding regions of all these people to see what kind of variation existed (Lek et al., 2016) (ExAC). The group included representatives from all parts of the world although it was heavily weighted toward Europeans. The authors used a procedure called "principal component analysis" (PCA) to cluster the individuals according to their genetic characteristics. The analysis led to the typical clustering by "population clusters." (That term is used to avoid the words "race" and/or "subspecies.")Thursday, January 05, 2017

Birth and death of genes in a hybrid frog genome

De novo genes1 are quite rare but genome duplications are quite common. Sometimes the duplicated regions contain genes so the new genome contains two copies of a gene that was formerly present in only one copy. "Common" in this sense means on a scale of millions of years. Michael Lynch and his colleague have calculated that the rate of fixed gene duplication is about 0.01 per gene per million years (Lynch and Conery, 2003 a,b; Lynch 2007). Since a typical vertebrate has more than 20,000 genes, this means that 200 genes will be duplicated and fixed every million years.

The initial duplication event is likely to be deleterious since there will now be redundant DNA in the genome. The slightly deleterious allele (duplication) can be purged by negative selection in species with large population sizes (e.g. bacteria). But in species with smaller populations, natural selection is not powerful enough to eliminate slightly deleterious alleles so the duplication persists and may become fixed in the population.

Tuesday, December 20, 2016

Is the high frequency of blood type O in native Americans due to random genetic drift?

The frequency of blood type O is very high in some populations of native Americans. In many North American tribes, for example, the frequency is over 90% and often approaches 100%. A majority of individuals in those populations have blood type O (homozygous for the O allele). [see Theme: ABO Blood Types]

Since there's no solid evidence that blood types are adaptive,1 the standard explanation is random genetic drift.Jerry Coyne explains it in Why Evolution Is True.

One example of evolution by drift may be the unusual frequencies of blood types (as in the ABO system) in the Old Order Amish and Dunker religious communities in America. These are small, isolated, religious groups whose members intermarry—just the right circumstances for rapid evolution by genetic drift.

Accidents of sampling can also happen when a population is founded by just a few immigrants, as occurs when individuals colonize an island or a new area. The almost complete absence of genes producing the B blood type in Native American populations, for example, may reflect the loss of this gene in a small population of humans that colonized North America from Asia around twelve thousand years ago.

Tuesday, August 23, 2016

Splice variants of the human triose phosphate isomerase gene: is alternative splicing real?

Triose phosphate isomerase (TIM) is one of the enzymes in the gluconeogenesis pathway leading to the synthesis of glucose from simple precursors. It also plays a role in the degradation of glucose (glycolysis). The enzyme catalyzes the following reaction ....

Triose phosphate isomerase is found in almost all species. The structure and sequence of the enzyme is well-conserved. It is a classic β-barrel enzyme that usually forms a dimer. The overall structure of a single subunit is classic example of an αβ-barrel known as a TIM-barrel in reference to this enzyme.

To the best of my knowledge, no significant variants of this enzyme due to alternative promoters, alternative splicing, or proteolytic cleavage are known.1 The enzyme has been actively studied in biochemistry laboratories for at least eighty years.

Thursday, July 28, 2016

False history and the number of genes: 2016

IT WAS a discovery that threatened to overturn everything we thought about what makes us human. At the dawn of the new millennium, two rival teams were vying to be the first to sequence the human genome. Their findings, published in February 2001, made headlines around the world. Back-of-the-envelope calculations had suggested that to account for the sheer complexity of human biology, our genome should contain roughly 100,000 genes. The estimate was wildly off. Both groups put the actual figure at around 30,000. We now think it is even fewer – just 20,000 or so.

"It was a massive shock," says geneticist John Mattick. "That number is tiny. It’s effectively the same as a microscopic worm that has just 1000 cells."

Sunday, July 10, 2016

What is a "gene" and how do genes work according to Siddhartha Mukherjee?

It's difficult to explain fundamental concepts of biology to the average person. That's why I'm so interested in Siddhartha Mukherjee's book "The Gene: an intimate history." It's a #1 bestseller so he must be doing something right.

A gene is a DNA sequence that is transcribed to produce a functional product.This covers two types of genes: those that eventually produce proteins (polypeptides); and those that produce functional noncoding RNAs. This distinction is important when discussing what's in our genome.

Wednesday, June 15, 2016

What does a person's genome reveal about their ethnicity and their appearance?

If you knew the complete genome sequence of someone could you tell where they came from and their ethnic background (race)? The answer is confusing according to Siddhartha Mukherjee writing in his latest book "The Gene: an intimate history." The answer appears to be "yes" but then Mukherjee denies that knowing where someone came from tells us anything about their genome or their phenotype. He writes the following on page 342.

... the genetic diversity within any racial group dominates the diversity between racial groups. This degree of intraracial variability makes "race" a poor surrogate for nearly any feature: in a genetic sense, an African man from Nigeria is so "different" from another man from Namibia that it makes little sense the lump them into the same category.I find this view very strange. Imagine that you were an anthropologist who was an expert on humans and human evolution. Imagine you were told that there's a woman in the next room whose eight great-grandparents all came from Japan. According to Mukherjee, such a scientist could not predict anything about the features of that woman. Does that make any sense?

For race and genetics, then, the genome is strictly a one-way street. You can use the genome to predict where X or Y came from. But knowing where A or B came from, you can predict little about the person's genome. Or: every genome carries a signature of an individual's ancestry—but an individual's racial ancestry predicts little about the person's genome. You can sequence DNA from an African-American man and conclude that his ancestors came from Sierra Leone or Nigeria. But if you encounter a man whose great-grandparents came from Nigeria or Sierra Leone, you can say little about the features of this particular man. The geneticist goes home happy; the racist returns empty-handed.

I suspect this is just a convoluted way of reconciling science with political correctness.

Steven Monroe Lipkin has a different view. He's a medical geneticist who recently published a book with Jon R. Luoma titled "The Age of Genomes: tales from the front lines of genetic medicine." Here's how they explain it on page 6.

Many ethnic groups carry distinct signatures. For example, from a genome sequence you can usually tell if an individual is African-American, Caucasian, Asian, Satnami, or Ashkenazi Jew, even if you've never laid eyes on the patient. A well-regarded research scientist whom I had never met made his genome sequence publically available as part of a research study. I remember scrolling through his genetic variant files and trying, more successfully than I had expected, to guess what he would look like before I peeked at his webpage photo. The personal genome is more than skin deep.This makes more sense to me. If you know what you look for—and Simon Monroe certainly does—then many of the features of a particular person can be deduced from their genome sequence. And if you know which variants are more common in certain ethnic groups then you can certainly predict what a person might look like just by knowing where their ancestors came from.

What's wrong with that?

Tuesday, May 24, 2016

University of Toronto press release distorts conclusions of RNA paper

Sharma, E., Sterne-Weiler, T., O’Hanlon, D., and Blencowe, B.J. (2016) Global Mapping of Human RNA-RNA Interactions. Molecular Cell, [doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.04.030]

ABSTRACT (Summary)

The majority of the human genome is transcribed into non-coding (nc)RNAs that lack known biological functions or else are only partially characterized. Numerous characterized ncRNAs function via base pairing with target RNA sequences to direct their biological activities, which include critical roles in RNA processing, modification, turnover, and translation. To define roles for ncRNAs, we have developed a method enabling the global-scale mapping of RNA-RNA duplexes crosslinked in vivo, ‘‘LIGation of interacting RNA followed by high-throughput sequencing’’ (LIGR-seq). Applying this method in human cells reveals a remarkable landscape of RNA-RNA interactions involving all major classes of ncRNA and mRNA. LIGR-seq data reveal unexpected interactions between small nucleolar (sno) RNAs and mRNAs, including those involving the orphan C/D box snoRNA, SNORD83B, that control steady-state levels of its target mRNAs. LIGR-seq thus represents a powerful approach for illuminating the functions of the myriad of uncharacterized RNAs that act via base-pairing interactions.

Thursday, January 28, 2016

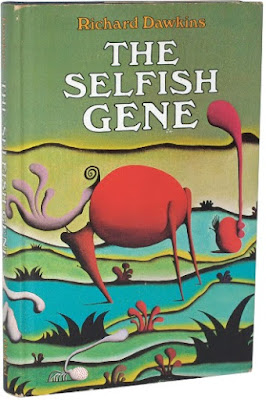

"The Selfish Gene" turns 40

I don't remember when I first read it—probably the following year when the paperback version came out. I found it quite interesting but I was a bit put off by the emphasis on adaptation (taken from George Williams) and the idea of inclusive fitness (from W.D. Hamilton). I also didn't much like the distinction between vehicles and replicators and the idea that it was the gene, not the individual, that was the unit of selection ("selection" not "evolution").

It is finally time to return to the problem with which we started, to the tension between individual organism and gene as rival candidates for the central role in natural selection...One way of sorting this whole matter out is to use the terms ‘replicator’ and ‘vehicle’. The fundamental units of natural selection, the basic things that survive or fail to survive, that form lineages of identical copies with occasional random mutations, are called replicators. DNA molecules are replicators. They generally, for reasons that we shall come to, gang together into large communal survival machines or ‘vehicles’.

Richard Dawkins

Sunday, January 17, 2016

Origin of de novo genes in humans

In spite of what you might have read in the popular literature, there are not a large number of newly formed genes in most species. Genes that appear to be unique to a single species are called "orphan" genes. When a genome is first sequenced there will always be a large number of potential orphan genes because the gene prediction software tilts toward false positives in order to minimize false negatives. Further investigation and annotation reduces the number of potential genes.

Thursday, December 10, 2015

How many human protein-coding genes are essential for cell survival?

It would be almost as interesting to know how many are required for just survival of a particular cell. This set is the group of so-called "housekeeping genes." They are necessary for basic metabolic activity and basic cell structure. Some of these genes are the genes for ribosomal RNA, tRNAs, the RNAs involved in splicing, and many other types of RNA. Some of them are the protein-coding genes for RNA polymerase subunits, ribosomal proteins, enzymes of lipid metabolism, and many other enzymes.

The ability to knock out human genes using CRISPR technology has opened to door to testing for essential genes in tissue culture cells. The idea is to disrupt every gene and screen to see if it's required for cell viability in culture.

Three papers using this approach have appeared recently:

Blomen, V.A., Májek, P., Jae, L.T., Bigenzahn, J.W., Nieuwenhuis, J., Staring, J., Sacco, R., van Diemen, F.R., Olk, N., and Stukalov, A. (2015) Gene essentiality and synthetic lethality in haploid human cells. Science, 350:1092-1096. [doi: 10.1126/science.aac7557 ]Each group identified between 1500 and 2000 protein-coding genes that are essential in their chosen cell lines.

Wang, T., Birsoy, K., Hughes, N.W., Krupczak, K.M., Post, Y., Wei, J.J., Lander, E. S., and Sabatini, D.M. (2015) Identification and characterization of essential genes in the human genome. Science, 350:1096-1101. [doi: 10.1126/science.aac7041]

Hart, T., Chandrashekhar, M., Aregger, M., Steinhart, Z., Brown, K.R., MacLeod, G., Mis, M., Zimmermann, M., Fradet-Turcotte, A., and Sun, S. (2015) High-Resolution CRISPR Screens Reveal Fitness Genes and Genotype-Specific Cancer Liabilities. Cell 163:1515-1526. [doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.015]

One of the annoying things about all three papers is that they use the words "gene" and "protein-coding gene" as synonyms. The only genes they screened were protein-coding genes but the authors act as though that covers ALL genes. I hope they don't really believe that. I hope it's just sloppy thinking when they say that their 1800 essential "genes" represent 9.2% of all genes in the genome (Wang et al. 2015). What they meant is that they represent 9.2% of protein-coding genes.

By looking only at genes that are essential for cell survival, they are ignoring all those genes that are specifically required in other cell types. For example, they will not identify any of the genes for olfactory receptors or any of the genes for keratin or collagen. They won't detect any of the genes required for spermatogenesis or embryonic development.

What they should detect is all of the genes required in core metabolism.

The numbers seen too low to me so I looked for some specific examples.

The HSP70 gene family encodes the major heat shock protein of molecular weight 70,000. The protein functions as a chaperone to help fold other proteins. They are among the most highly conserved genes in all of biology and they are essential. The three genes for the normal cellular proteins are HSPA5 (Bip, the ER protein); HSPA8 (the cytoplasmic version); and HSPA9 (mitochondrial version). All three are essential in the Blomen et al. paper. Only HSPA5 and HSPA9 are essential in Hunt et al. (This is an error.) (I can't figure out how to identify essential genes in the Wang et al. paper.)

There are two inducible genes, HSPA1A and HSPA1B. These are the genes activated by heat shock and other forms of stress and they churn out a lot of HSP70 chaperone in order to save the cells. There are not essential genes in the Blomen et al. paper and they weren't tested in the Hunt et al. paper. This is an example of the kind of gene that will be missed in the screen because the cells were not stressed during the screening.

I really don't like these genomics papers because all they do is summarize the results in broad terms. I want to know about specific genes so I can see if the results conform to expectations.

I looked first at the genes encoding the enzymes for gluconeogenesis and glycolysis. The results are from the Blomen et al. paper. In the figure below, the genes names in RED are essential and the ones in blue are not.

As you can see, at least one of the genes for the six core enzymes is essential. But none of the other genes is essential. This is a surprise since I expect both pathways (gluconeogenesis and glycolysis) to be active and essential in those cells. Perhaps the cells can survive for a few days without making these enzymes. It means they can't take up glucose because one of the hexokinase enzymes should be essential.

These result suggest that the Blomen et al. study is overlooking some important essential genes.

Now let's look at the citric acid cycle. All of the enzymes should be essential.

That's very strange. It's hard to imagine that cells in culture can survive without any of the genes for the subunits of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex or the subunits of the succinyl C0A synthetase complex. Or malate dehydrogenase, for that matter.

Something is wrong here. The study must be missing some important essential genes. I wish the authors had looked at some specific sets of genes and told us the results for well-known genes. That would allow us to evaluate the results. Perhaps this sort of thing isn't done when you are in "genomics" mode?

The "core fitness" protein-coding genes that were identified are more highly conserved than the other genes and they tend to be more highly expressed. They also show lower levels of variation within the human population. This is consistent with basic housekeeping features.

Each group identified several hundred unannotated genes in their core sample. These are genes with no known function (yet).

The results of the three studies do not overlap precisely but most of the essential genes were common to all three analyses.

Wednesday, November 25, 2015

Selfish genes and transposons

Some scientists were experts in modern evolutionary theory but still wanted to explain "junk DNA." Doolittle & Sapienza, and Orgel & Crick, published back-to-back papers in the April 17, 1980 issue of Nature. They explained junk DNA by claiming that most of it was due to the presence of "selfish" transposons that were being selected and preserved because they benefited their own replication and transmission to future generations. They have no effect on the fitness of the organism they inhabit. This is natural selection at a different level.

This prompted some responses in later editions of the journal and then responses to the responses.

Here's the complete series ...

Friday, November 20, 2015

Different kinds of pseudogenes: Polymorphic pseudogenes

There's one sub-category of pseudogenes that deserves mentioning. It's called "polymorphic pseudogenes." These are pseudogenes that have not become fixed in the genome so they exist as an allele along with the functional gene at the same locus. Some defective genes might be detrimental, representing loss-of-function alleles that compromise the survival of the organism. Lots of genes for genetic diseases fall into this category. That's not what we mean by polymorphism. The term usually applies to alleles that have reached substantial frequency in the population so that there's good reason to believe that all alleles are about equal with respect to natural selection.

Polymorphic pseudogenes can be examples of pseudogenes that are caught in the act of replacing the functional gene. This indicates that the functional gene is not under strong selection. For example, a newly formed processed pseudogene can be polymorphic at the insertion site and newly duplicated loci may have some alleles that are still functional and others that are inactive. The fixation of a pseudogene takes a long time.

Different kinds of pseudogenes: Unitary pseudogenes

The third type of pseudogene is the "unitary" pseudogene. Unitary pseudogenes are genes that have no parent gene. There is no functional gene in the genome that's related to the pseudogene.

Unitary psedogenes arise when a normally functional gene becomes inactivated by mutation and the loss of function is not detrimental to the organism. Thus, the mutated, inactive, gene can become fixed in the population by random genetic drift.

The classic example is the gene for L-glucono-γ-lactone oxidase (GULO), a key enzyme in the synthesis of vitamin C (L-ascorbate, ascorbic acid). This gene is functional in most vertebrate species because vitamin C is required as a cofactor in several metabolic reactions; notably, the processing of collagen [Vitamin C]. This gene has become inactive in primates so primates cannot synthesize Vitamin C and must obtain it from the food they eat.

A pseudogene can be found at the locus for the L-glucono-γ-lactone oxidase gene[GULOP = GULO Pseudogene]. It is a highly degenerative pseudogene with multiple mutations and deletions [Human GULOP Pseudogene]

This is a unitary pseudogene. Unitary pseudogenes are rare compared to processed pseudogenes and duplicated pseudogenes but they are distinct because they are not derived from an existing, functional, parent gene.

Note: Intelligent design creationists will go to great lengths to discredit junk DNA. They will even attempt to prove that the GULO pseudogene is actually functional. Jonathan Wells devoted an entire chapter in The Myth of Junk DNA to challenging the idea that the GULO pseudogene is actually a pseudogene. A few years ago, Jonathan McLatchie proposed a mechanism for creating a functional enzyme from the bits and pieces of the human GULOP pseudogene but that proved embarrasing and he retracted [How IDiots Would Activate the GULO Pseudogene] Although some scientists are skeptical about the functionality of some pseudogenes, they all accept the evidence showing that most psuedogenes are nonfunctional.

Different kinds of pseudgogenes: Duplicated pseudogenes

I've assumed, in the example shown below, that the gene duplication event happens by recombination between sister chromosomes when they are aligned during meiosis. That's not the only possibility but it's easy to understand.

These sorts of gene duplication events appear to be quite common judging from the frequency of copy number variations in complex genomes (Redon et al., 2006; MacDonald et al., 2013).

Wednesday, November 18, 2015

Different kinds of pseudogenes: Processed pseudogenes

This is most obvious in the case of processed pseudogenes derived from eukaryotic protein-coding genes so that's the example I'll describe first.

In the example below, I start with a simple, hypothetical, protein-coding gene consisting of two exons and a single intron. The gene is transcribed from a promoter (P) to produce the primary transcript containing the intron. This primary transcript is processed by splicing to remove the intron sequence and join up the exons into a single contiguous open reading frame that can be translated by the protein synthesis machinery (ribosomes plus factors etc.).1 [See RNA Splicing: Introns and Exons.]

Different kinds of pseudogenes - are they really pseudogenes?

A pseudogene is a broken gene that cannot produce a functional RNA. They are called "pseudogenes" because they resemble active genes but carry mutations that have rendered them nonfunctional. The human genome contains about 14,000 pseudogenes related to protein-coding genes according to the latest Ensembl Genome Reference Consortium Human Genome build [GRCh38.p3]. There's some controversy over the exact number but it's certainly in that ballpark.1

The GENCODE Pseudogene Resource is the annotated database used by Ensembl and ENCODE (Pei et al. 2012).

There are an unknown number of pseudogenes derived from genes for noncoding functional RNAs. These pseudogenes are more difficult to recognize but some of them are present in huge numbers of copies. The Alu elements in the human genome are derived from 7SL RNA and there are similar elements in the mouse genome that are derived from tRNA genes.

There are three main classes of pseudogenes and one important subclass. The categories apply to pseudogenes derived from protein-coding genes and to those derived from genes that specify functional noncoding RNAs. I'm going to describe each of the categories in separate posts. I'll mostly describe them using a protein-coding gene as the parent.

1. Processed pseudogenes [Processed pseudogenes ]

2. Duplicated pseudogenes [Duplicated pseudogenes ]

3. Unitary pseudogenes [Unitary Pseudogenes]

4. subclass: Polymorphic pseudogenes [Polymorphic Pseudogenes]

Monday, November 09, 2015

How many proteins do humans make?

This jumble of different kinds of genes makes it difficult to estimate the total number of genes in the human genome. The current estimates are about 20,000 protein-coding genes and about 5,000 genes for functional RNAs.

Aside from the obvious highly conserved genes for ubiquitous RNAs (rRNA, tRNAs etc.), protein-coding genes are the easiest to recognize from looking at a genome sequence. If the protein is expressed in many different species then the exon sequences will be conserved and it's easy for a computer program to identify the gene. The tough part comes when the algorithm predicts a new protein-coding gene based on an open reading frame spanning several presumed exons. Is it a real gene?

Sunday, November 01, 2015

More stupid hype about lncRNAs

They did no such thing. What they discovered was about 3,000 previously unidentified transcripts expressed at very low levels in human B cells and T cells. They declared that these low-level transcripts are lncRNAs and they assumed that the complementary DNA sequences were genes. Their actual result identifies 3,000 bits of the genome that may or may not turn out to be genes. They are PUTATIVE genes.

None of that deterred Karen Ring who blogs at The Stem Cellar: The Official Blog of CIRM, California's Stem Cell Agency. Her post on this subject [UCLA Scientists Find 3000 New Genes in “Junk DNA” of Immune Stem Cells] begins with ...